Factfulness by Rosling

Ref: Hans Rosling (2019). Factfulness. Flatiron Publishing.

__________________________________________________________________________

Summary

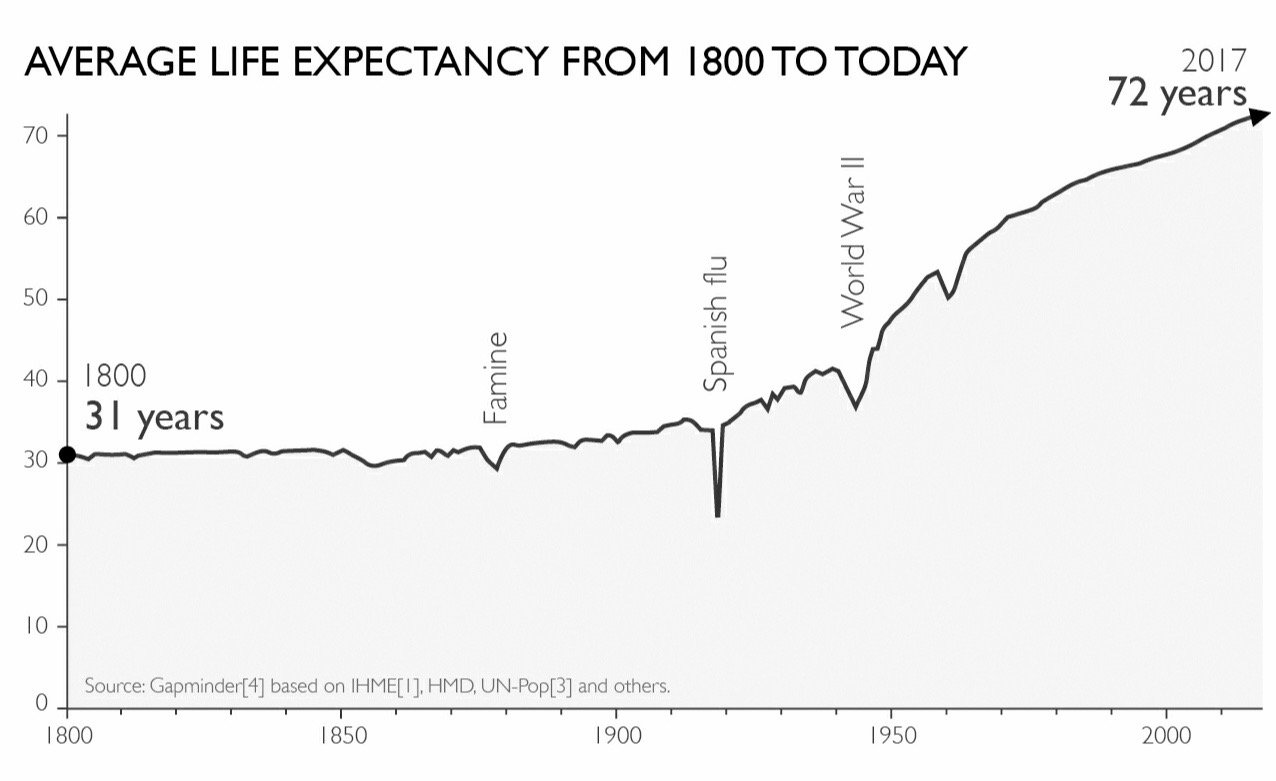

Our brains often jump to swift conclusions without much thinking, which used to help us to avoid immediate dangers. We are interested in gossip and dramatic stories, which used to be the only source of news and useful information. We crave sugar and fat, which used to be life-saving sources of energy when food was scarce. We have many instincts that used to be useful thousands of years ago, but we live in a very different world now. Our cravings for sugar and fat make obesity one of the largest health problems in the world today. We have to teach our children, and ourselves, to stay away from sweets and chips. In the same way, our quick-thinking brains and cravings for drama—our dramatic instincts—are causing misconceptions and an overdramatic worldview.

If we sifted every input and analyzed every decision rationally, a normal life would be impossible. We should not cut out all sugar and fat, and we should not ask a surgeon to remove the parts of our brain that deal with emotions. But we need to learn to control our drama intake.

Human beings have a strong dramatic instinct toward binary thinking.

Most people prefer to focus on the unusual rather than the common, and on the new or temporary rather than slowly changing patterns.

The overdramatic worldview in people’s heads creates a constant sense of crisis and stress. The urgent “now or never” feelings it creates lead to stress or apathy: “We must do something drastic. Let’s not analyze. Let’s do something.” Or, “It’s all hopeless. There’s nothing we can do. Time to give up.” Either way, we stop thinking, give in to our instincts, and make bad decisions.

There is no conflict between celebrating this progress and continuing to fight for more.

The simple and beautiful idea of equality can lead to the simplistic idea that all problems are caused by inequality, which we should always oppose; and that the solution to all problems is redistribution of resources, which we should always support. It saves a lot of time to think like this. You can have opinions and answers without having to learn about a problem from scratch and you can get on with using your brain for other tasks. But it’s not so useful if you like to understand the world. Being always in favor of or always against any particular idea makes you blind to information that doesn’t fit your perspective. This is usually a bad approach if you like to understand reality.

There is no single indicator through which we can measure the progress of a nation. Reality is just more complicated than that. The world cannot be understood without numbers, nor through numbers alone. A country cannot function without a government, but the government cannot solve every problem. Neither the public sector nor the private sector is always the answer. No single measure of a good society can drive every other aspect of its development. It’s not either/or. It’s both and it’s case-by-case.

__________________________________________________________________________

—Instincts—

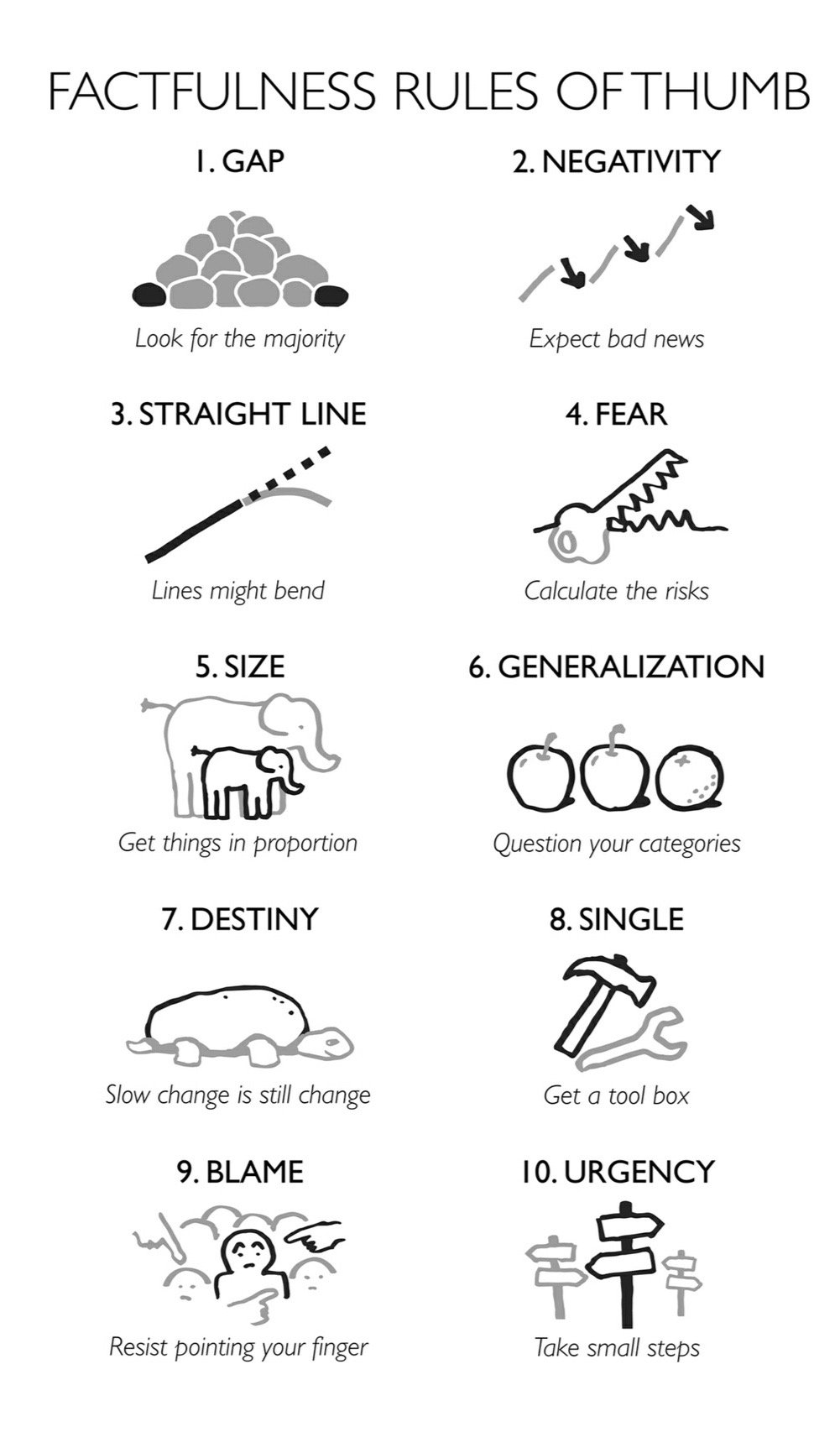

Gap Instinct

The Gap Instinct: the irresistible temptation we have to divide all kinds of things into two distinct and often conflicting groups, with an imagined gap—a huge chasm of injustice—in between. The gap instinct creates a picture in people’s heads of a world split into two kinds of countries or two kinds of people: rich versus poor.

The gap instinct makes us imagine division where there is just a smooth range; difference where there is convergence, and conflict where there is agreement.

The fact that extremes exist doesn’t tell us much. Usually, the majority is right there in the middle, where the gap is supposed to be. To control the gap instinct, look for the majority.

Beware comparisons of averages. If you could check the spreads you would probably find they overlap. There is probably no gap at all. • Beware comparisons of extremes. In all groups, of countries or people, there are some at the top and some at the bottom. The difference is sometimes extremely unfair. But even then the majority is usually somewhere in between, right where the gap is supposed to be. • The view from up here. Remember, looking down from above distorts the view. Everything else looks equally short, but it’s not.

We almost always get a more accurate picture by digging a little deeper and looking not just at the averages but at the spread: not just the group all bundled together, but the individuals.

Negativity Instinct

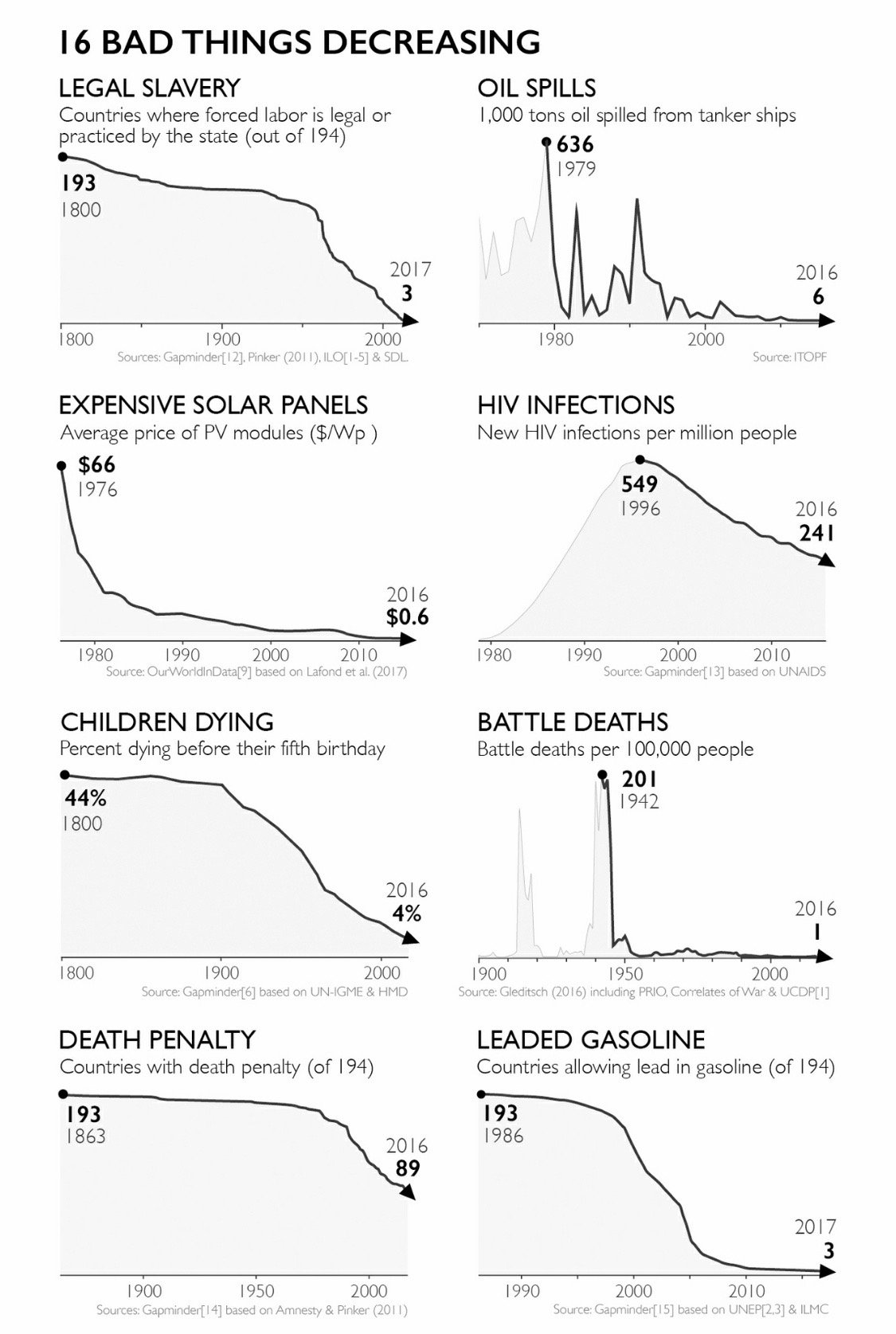

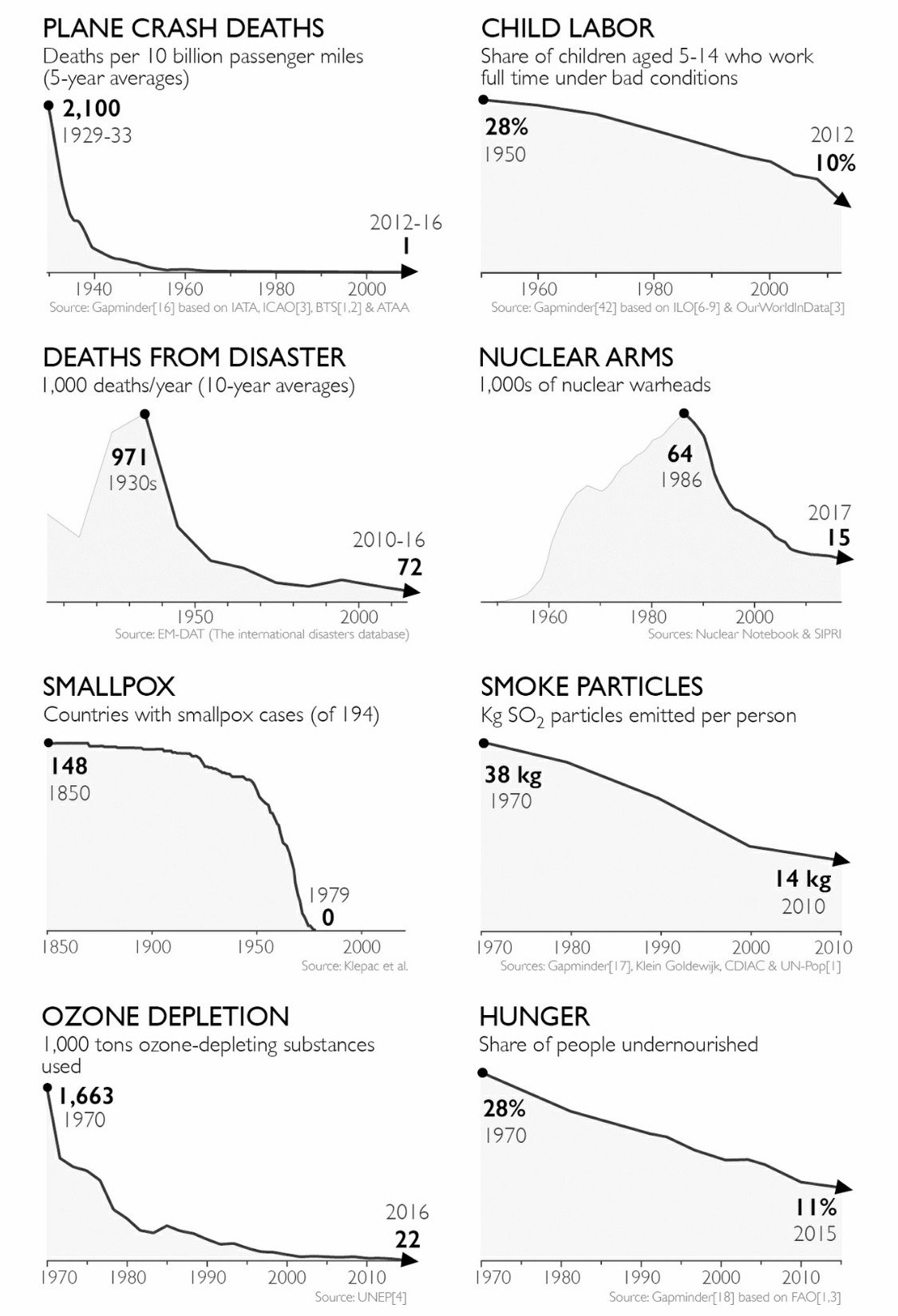

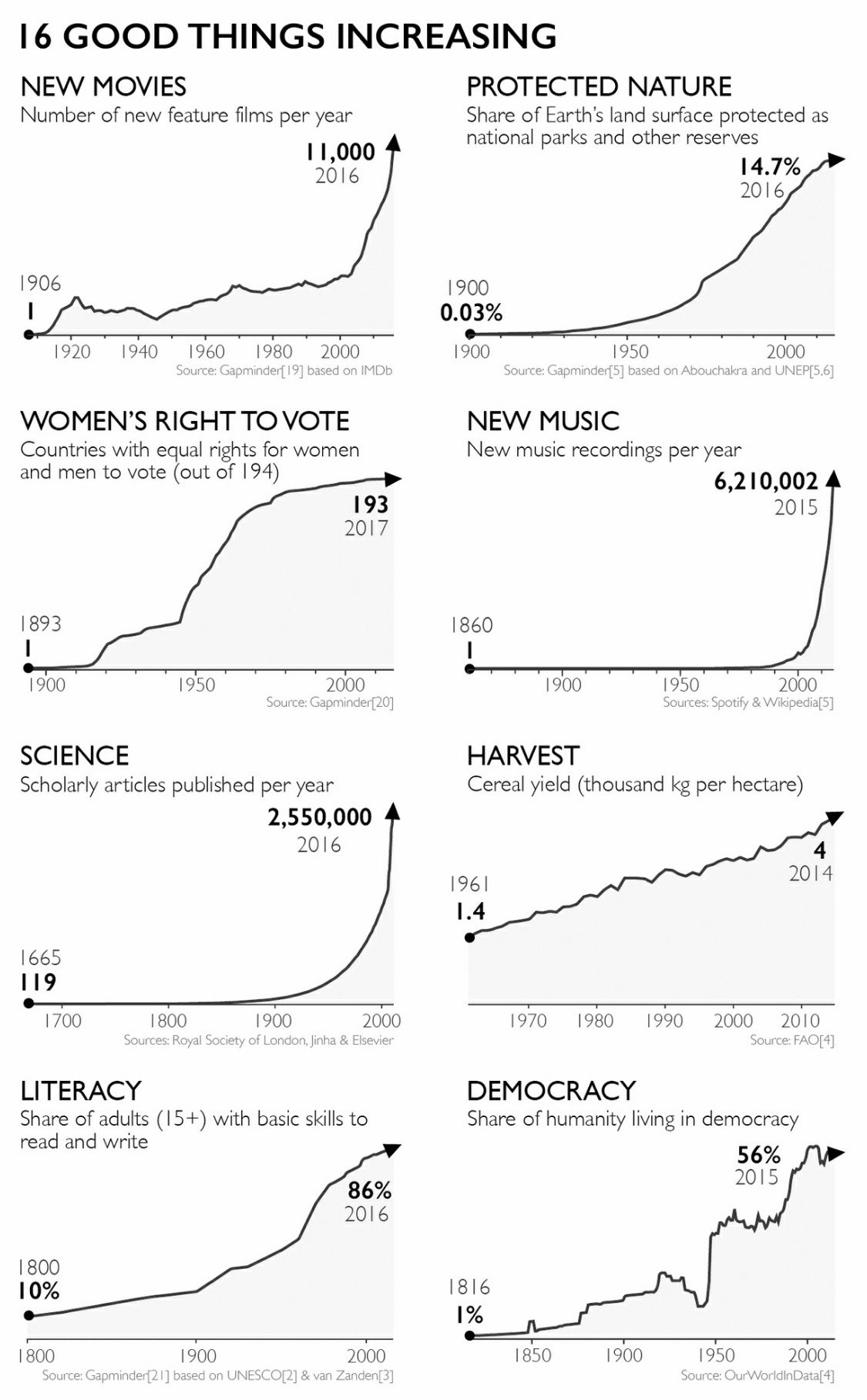

Negativity Instinct: our instinct to notice the bad more than the good. There are three things going on here: the misremembering of the past; selective reporting by journalists and activists; and the feeling that as long as things are bad it’s heartless to say they are getting better.

Our tendency to notice the bad more than the good.

Whenever we talk about the future we should be open and clear about the level of uncertainty involved. We should not pick the most dramatic estimates and show a worst-case scenario as if it were certain.

Recognizing when we get negative news, and remembering that information about bad events is much more likely to reach us. When things are getting better we often don’t hear about them. This gives us a systematically too-negative impression of the world around us, which is very stressful. To control the negativity instinct, expect bad news.

Better and bad: Practice distinguishing between a level (e.g., bad) and a direction of change (e.g., better). Convince yourself that things can be both better and bad.

Good news is not news: Good news is almost never reported. So news is almost always bad. When you see bad news, ask whether equally positive news would have reached you. More news does not equal more suffering: More bad news is sometimes due to better surveillance of suffering, not a worsening world.

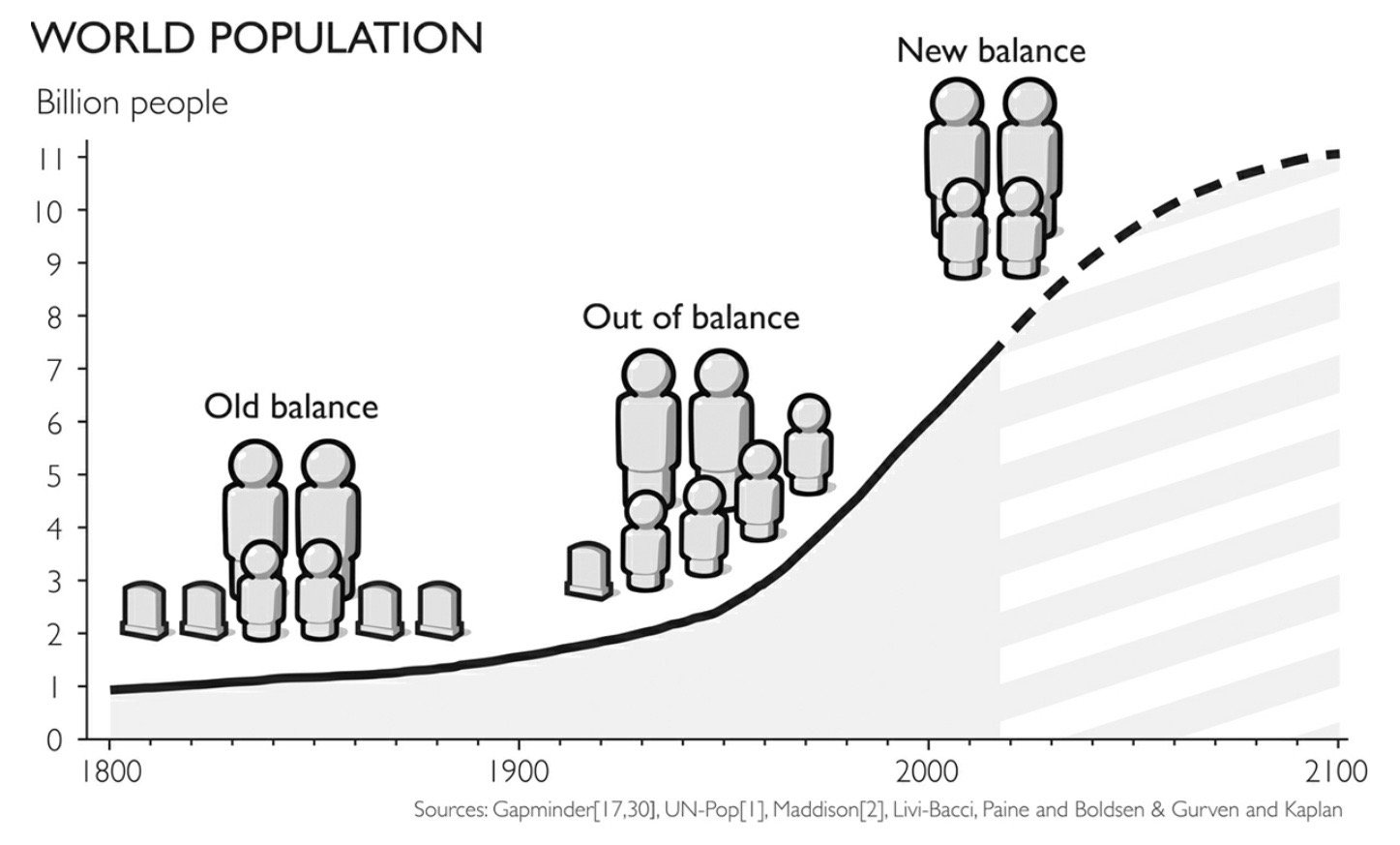

Straight Line Instinct

Straight Line Instinct: An apparently straight upward trend could be part of a straight line, an S-bend, a hump, or a doubling line. An apparently straight downward trend could be part of a straight line, a slide, or a hump. Any two connected points look like a straight line but when we have three points we can distinguish between a straight line (1, 2, 3) and the start of what may be a doubling line (1, 2, 4).

Recognizing the assumption that a line will just continue straight, and remembering that such lines are rare in reality. To control the straight line instinct, remember that curves come in different shapes. • Don’t assume straight lines. Many trends do not follow straight lines but are S-bends, slides, humps, or doubling lines. No child ever kept up the rate of growth it achieved in its first six months, and no parents would expect it to.

Fear Instinct

The fear instinct is a terrible guide for understanding the world. It makes us give our attention to the unlikely dangers that we are most afraid of, and neglect what is actually most risky.

Data exists for almost every aspect of global development. And yet, because of our dramatic instincts and the way the media must tap into them to grab our attention, we continue to have an overdramatic worldview. Of all our dramatic instincts, it seems to be the fear instinct that most strongly influences what information gets selected by news producers and presented to us consumers.

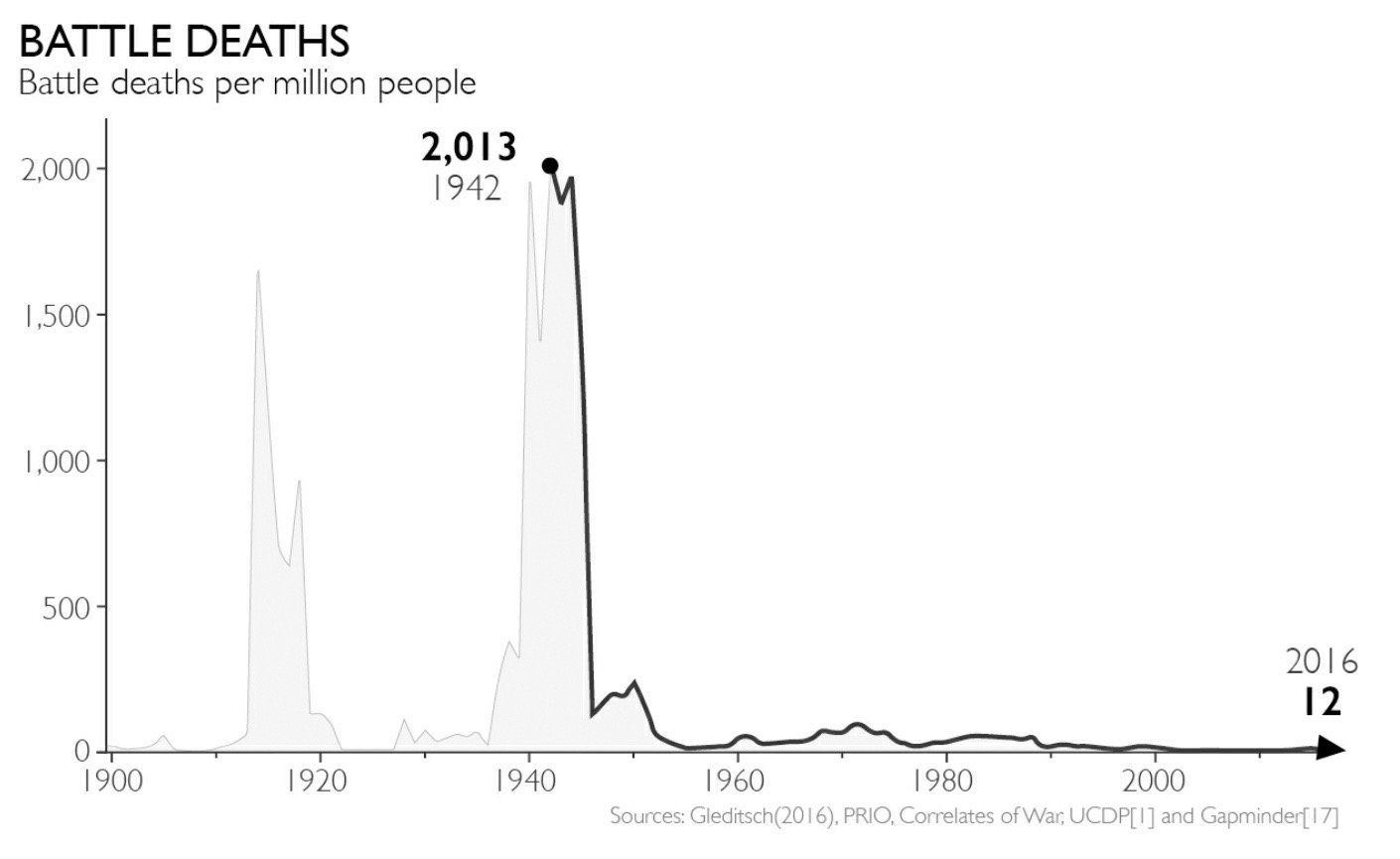

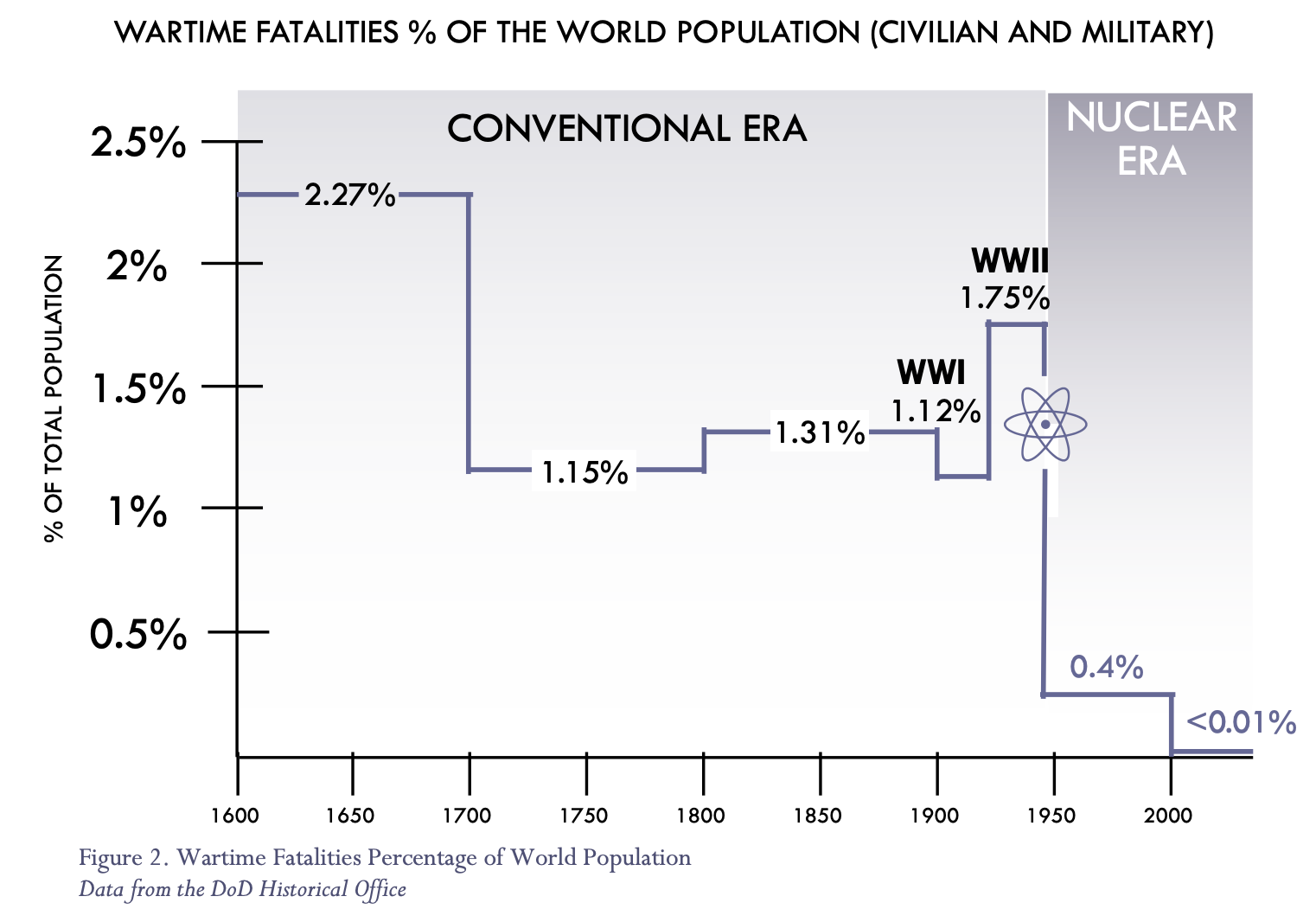

Yet here’s the paradox: the image of a dangerous world has never been broadcast more effectively than it is now, while the world has never been less violent and more safe.

Something frightening poses a perceived risk. Something dangerous poses a real risk. Paying too much attention to what is frightening rather than what is dangerous—that is, paying too much attention to fear—creates a tragic drainage of energy in the wrong directions.

Critical thinking is always difficult, but it’s almost impossible when we are scared. There’s no room for facts when our minds are occupied by fear.

Skilled journalists pick and choose dramatic exceptional people in their reports.

The extreme deprivation we see on the news ends up stereotyping the majority of mankind.

Recognizing when frightening things get our attention, and remembering that these are not necessarily the most risky. Our natural fears of violence, captivity, and contamination make us systematically overestimate these risks. To control the fear instinct, calculate the risks. • The scary world: fear vs. reality. The world seems scarier than it is because what you hear about it has been selected—by your own attention filter or by the media—precisely because it is scary. • Risk = danger × exposure. The risk something poses to you depends not on how scared it makes you feel, but on a combination of two things. How dangerous is it? And how much are you exposed to it? • Get calm before you carry on. When you are afraid, you see the world differently. Make as few decisions as possible until the panic has subsided.

Urgency Instinct

Urgency Instinct: “Act now, or lose the chance forever.” They are deliberately triggering your urgency instinct. The call to action makes you think less critically, decide more quickly, and act now.

The urgency instinct makes us want to take immediate action in the face of a perceived imminent danger.

When people tell me we must act now, it makes me hesitate.

Fear plus urgency make for stupid, drastic decisions with unpredictable side effects.

Exaggeration undermines the credibility of well-founded data: in this case, data showing that climate change is real, that it is largely caused by greenhouse gases from human activities such as burning fossil fuels, and that taking swift and broad action now would be cheaper than waiting until costly and unacceptable climate change happened. Exaggeration, once discovered, makes people tune out altogether.

When a problem seems urgent the first thing to do is not to cry wolf, but to organize the data.

We know that 800 million are suffering right now. We also know the solutions: peace, schooling, universal basic health care, electricity, clean water, toilets, contraceptives, and microcredits to get market forces started. There’s no innovation needed to end poverty. It’s all about walking the last mile with what’s worked everywhere else.

These risks require global collaboration and global resourcing. These risks should be approached through baby steps and constant evaluation, not through drastic actions.

Control your urgency instinct. Control all your dramatic instincts. Be less stressed by the imaginary problems of an overdramatic world, and more alert to the real problems and how to solve them.

Recognizing when a decision feels urgent and remembering that it rarely is. To control the urgency instinct, take small steps. • Take a breath. When your urgency instinct is triggered, your other instincts kick in and your analysis shuts down. Ask for more time and more information. It’s rarely now or never and it’s rarely either/or. • Insist on the data. If something is urgent and important, it should be measured. Beware of data that is relevant but inaccurate, or accurate but irrelevant. Only relevant and accurate data is useful. • Beware of fortune-tellers. Any prediction about the future is uncertain. Be wary of predictions that fail to acknowledge that. Insist on a full range of scenarios, never just the best or worst case. Ask how often such predictions have been right before. • Be wary of drastic action. Ask what the side effects will be. Ask how the idea has been tested. Step-by-step practical improvements, and evaluation of their impact, are less dramatic but usually more effective.

Size Instinct

The Size Instinct: You tend to get things out of proportion. I do not mean to sound rude. Getting things out of proportion, or misjudging the size of things, is something that we humans do naturally. It is instinctive to look at a lonely number and misjudge its importance.

When I see a lonely number in a news report, it always triggers an alarm: What should this lonely number be compared to? What was that number a year ago? Ten years ago? What is it in a comparable country or region? And what should it be divided by? What is the total of which this is a part? What would this be per person? I compare the rates, and only then do I decide whether it really is an important number.

Recognizing when a lonely number seems impressive (small or large), and remembering that you could get the opposite impression if it were compared with or divided by some other relevant number. To control the size instinct, get things in proportion. • Compare. Big numbers always look big. Single numbers on their own are misleading and should make you suspicious. Always look for comparisons. Ideally, divide by something. • 80/20. Have you been given a long list? Look for the few largest items and deal with those first. They are quite likely more important than all the others put together. • Divide. Amounts and rates can tell very different stories. Rates are more meaningful, especially when comparing between different-sized groups. In particular, look for rates per person when comparing between countries or regions.

Generalization Instinct

The Generalization Instinct: The necessary and useful instinct to generalize distorts our worldview. It can make us mistakenly group together things, or people, or countries that are actually very different. It can make us assume everything or everyone in one category is similar. And, maybe most unfortunate of all, it can make us jump to conclusions about a whole category based on a few, or even just one, unusual example.

Stereotype: General awareness of a problematic generalization.

The gap instinct divides the world into “us” and “them,” and the generalization instinct makes “us” think of “them” as all the same.

When seemingly impregnable logic is combined with good intentions, it becomes nearly impossible to spot the generalization error.

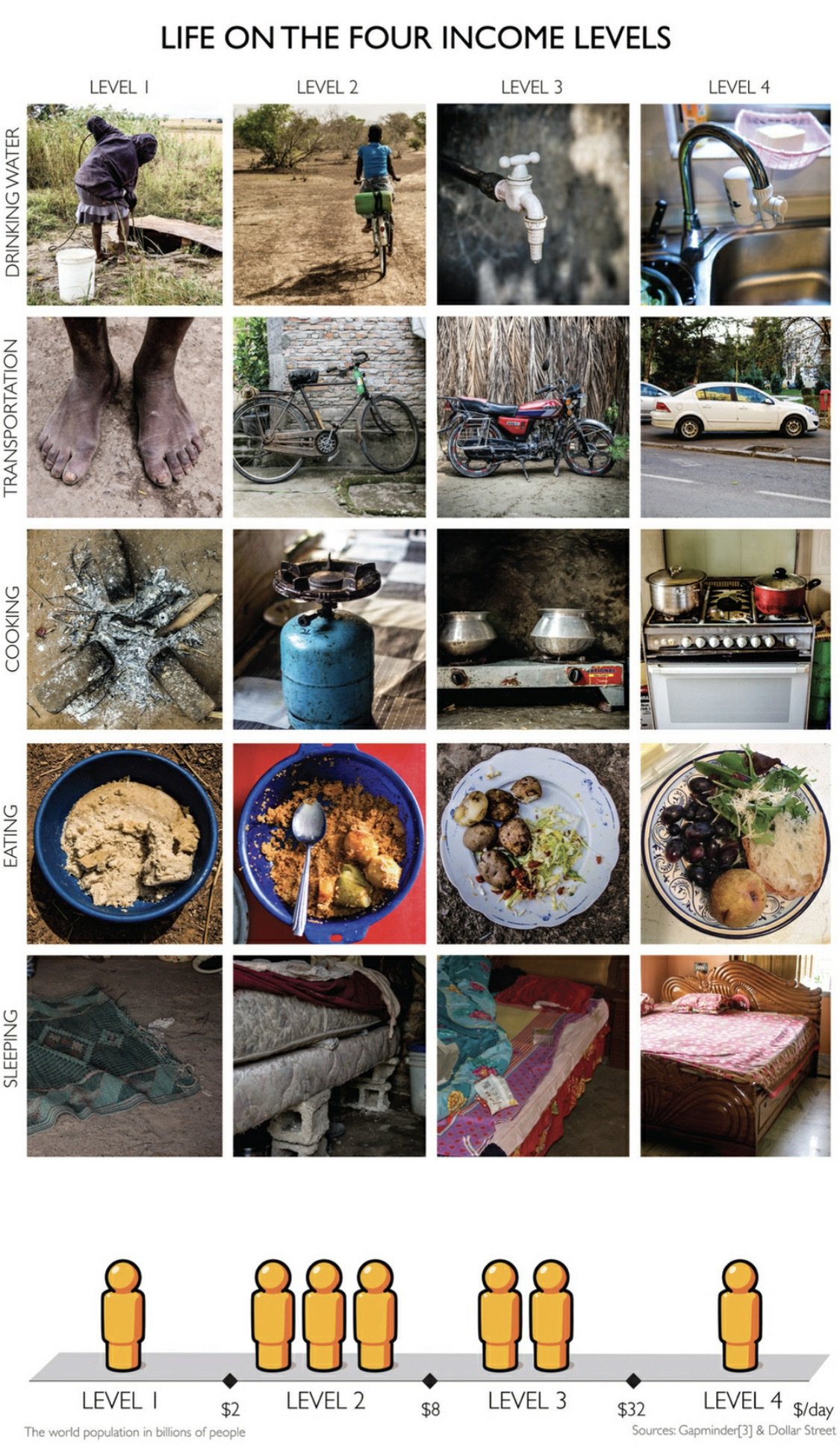

Stay open to the possibility that your experience might not be “normal.” Be cautious about generalizing from Level 4 experiences to the rest of the world. Especially if it leads you to the conclusion that other people are idiots.

Individual did something because they belong to some group—a nation, a culture, a religion—take care. Are there examples of different behavior in the same group? Or of the same behavior in other groups?

Recognizing when a category is being used in an explanation, and remembering that categories can be misleading. We can’t stop generalization and we shouldn’t even try. What we should try to do is to avoid generalizing incorrectly. To control the generalization instinct, question your categories. • Look for differences within groups. Especially when the groups are large, look for ways to split them into smaller, more precise categories. And … • Look for similarities across groups. If you find striking similarities between different groups, consider whether your categories are relevant. But also … • Look for differences across groups. Do not assume that what applies for one group (e.g., you and other people living on Level 4 or unconscious soldiers) applies for another (e.g., people not living on Level 4 or sleeping babies). • Beware of “the majority.” The majority just means more than half. Ask whether it means 51 percent, 99 percent, or something in between. • Beware of vivid examples. Vivid images are easier to recall but they might be the exception rather than the rule. • Assume people are not idiots. When something looks strange, be curious and humble, and think, In what way is this a smart solution?

Destiny Instinct

The Destiny Instinct: The idea that innate characteristics determine the destinies of people, countries, religions, or cultures. It’s the idea that things are as they are for ineluctable, inescapable reasons: they have always been this way and will never change. This instinct makes us believe that our false generalizations or tempting gaps are not only true, but fated: unchanging and unchangeable.

It’s easy to understand how claiming a particular destiny for your group can come in useful in uniting that group around a supposedly never-changing purpose, and perhaps creating a sense of superiority over other groups.

Beware of rosy pasts: People often glorify their early experiences, and nations often glorify their histories.

Recognizing that many things (including people, countries, religions, and cultures) appear to be constant just because the change is happening slowly, and remembering that even small, slow changes gradually add up to big changes. To control the destiny instinct, remember slow change is still change. • Keep track of gradual improvements. A small change every year can translate to a huge change over decades. • Update your knowledge. Some knowledge goes out of date quickly. Technology, countries, societies, cultures, and religions are constantly changing. • Talk to Grandpa. If you want to be reminded of how values have changed, think about your grandparents’ values and how they differ from yours. • Collect examples of cultural change. Challenge the idea that today’s culture must also have been yesterday’s, and will also be tomorrow’s.

Blame Instinct

The Blame Instinct: Makes us exaggerate the importance of individuals or of particular groups. This instinct to find a guilty party derails our ability to develop a true, fact-based understanding of the world: it steals our focus as we obsess about someone to blame, then blocks our learning because once we have decided who to punch in the face we stop looking for explanations elsewhere. This undermines our ability to solve the problem, or prevent it from happening again, because we are stuck with oversimplistic finger pointing, which distracts us from the more complex truth and prevents us from focusing our energy in the right places.

Resist the urge to blame the media for lying to you (mostly they are not) or for giving you a skewed worldview (which mostly they are, but often not deliberately).

Recognizing when a scapegoat is being used and remembering that blaming an individual often steals the focus from other possible explanations and blocks our ability to prevent similar problems in the future. To control the blame instinct, resist finding a scapegoat.

Look for causes, not villains. When something goes wrong don’t look for an individual or a group to blame. Accept that bad things can happen without anyone intending them to. Instead spend your energy on understanding the multiple interacting causes, or system that created the situation.

Single Perspective Instinct

Your most important challenge in developing a fact-based worldview is to realize that most of your firsthand experiences are from Level 4; and that your secondhand experiences are filtered through the mass media, which loves non-representative extraordinary events and shuns normality.

If you want to convince someone they are suffering from a misconception, it’s very useful to be able to test their opinion against the data.

Constantly test your favorite ideas for weaknesses. Be humble about the extent of your expertise. Be curious about new information that doesn’t fit, and information from other fields. And rather than talking only to people who agree with you, or collecting examples that fit your ideas, see people who contradict you, disagree with you, and put forward different ideas as a great resource for understanding the world.

Look for systems, not heroes. When someone claims to have caused something good, ask whether the outcome might have happened anyway, even if that individual had done nothing. Give the system some credit.

Recognizing that a single perspective can limit your imagination, and remembering that it is better to look at problems from many angles to get a more accurate understanding and find practical solutions. To control the single perspective instinct, get a toolbox, not a hammer. • Test your ideas. Don’t only collect examples that show how excellent your favorite ideas are. Have people who disagree with you test your ideas and find their weaknesses. • Limited expertise. Don’t claim expertise beyond your field: be humble about what you don’t know. Be aware too of the limits of the expertise of others. • Hammers and nails. If you are good with a tool, you may want to use it too often. If you have analyzed a problem in depth, you can end up exaggerating the importance of that problem or of your solution. Remember that no one tool is good for everything. If your favorite idea is a hammer, look for colleagues with screwdrivers, wrenches, and tape measures. Be open to ideas from other fields. • Numbers, but not only numbers. The world cannot be understood without numbers, and it cannot be understood with numbers alone. Love numbers for what they tell you about real lives. • Beware of simple ideas and simple solutions. History is full of visionaries who used simple utopian visions to justify terrible actions. Welcome complexity. Combine ideas. Compromise. Solve problems on a case-by-case basis.

Hero/Victim Instinct (added)

To understand most of the world’s significant problems we have to look beyond a guilty individual and to the system.

I remember the words of Ingegerd Rooth, who had been working as a missionary nurse in Congo and Tanzania before she became my mentor. She always told me, “In the deepest poverty you should never do anything perfectly. If you do you are stealing resources from where they can be better used.” Paying too much attention to the individual visible victim rather than to the numbers can lead us to spend all our resources on a fraction of the problem, and therefore save many fewer lives. This principle applies anywhere we are prioritizing scarce resources. It is hard for people to talk about resources when it comes to saving lives, or prolonging or improving them. Doing so is often taken for heartlessness. Yet so long as resources are not infinite—and they never are infinite—it is the most compassionate thing to do to use your brain and work out how to do the most good with what you have.

__________________________________________________________________________

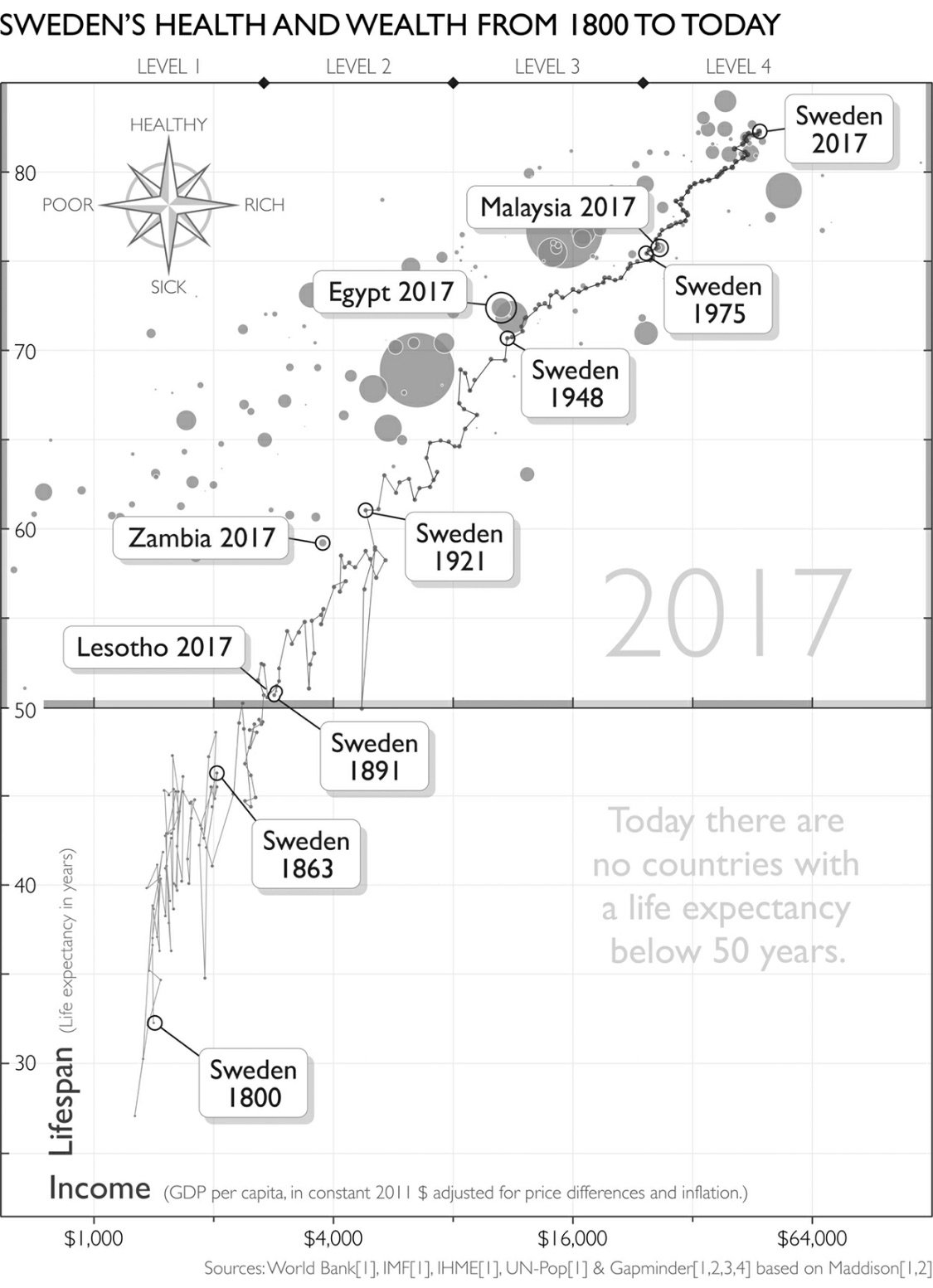

Factfulness in Population

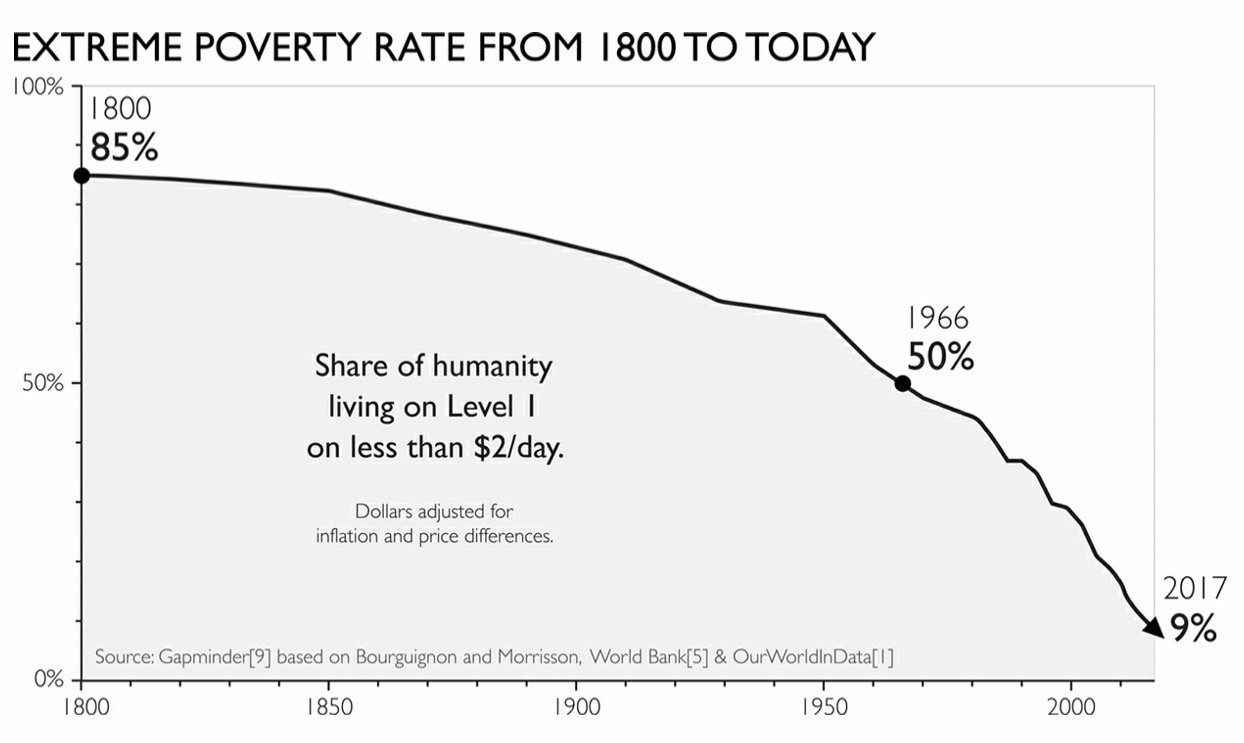

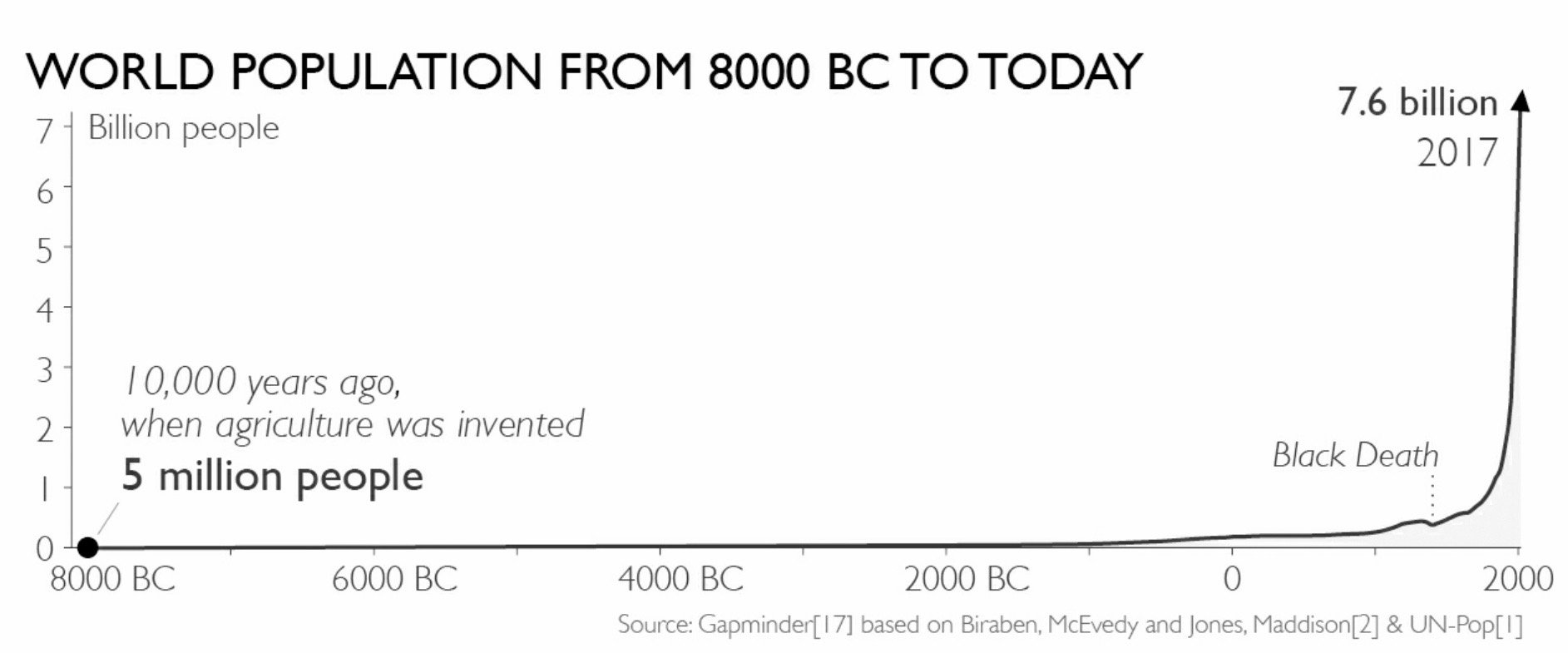

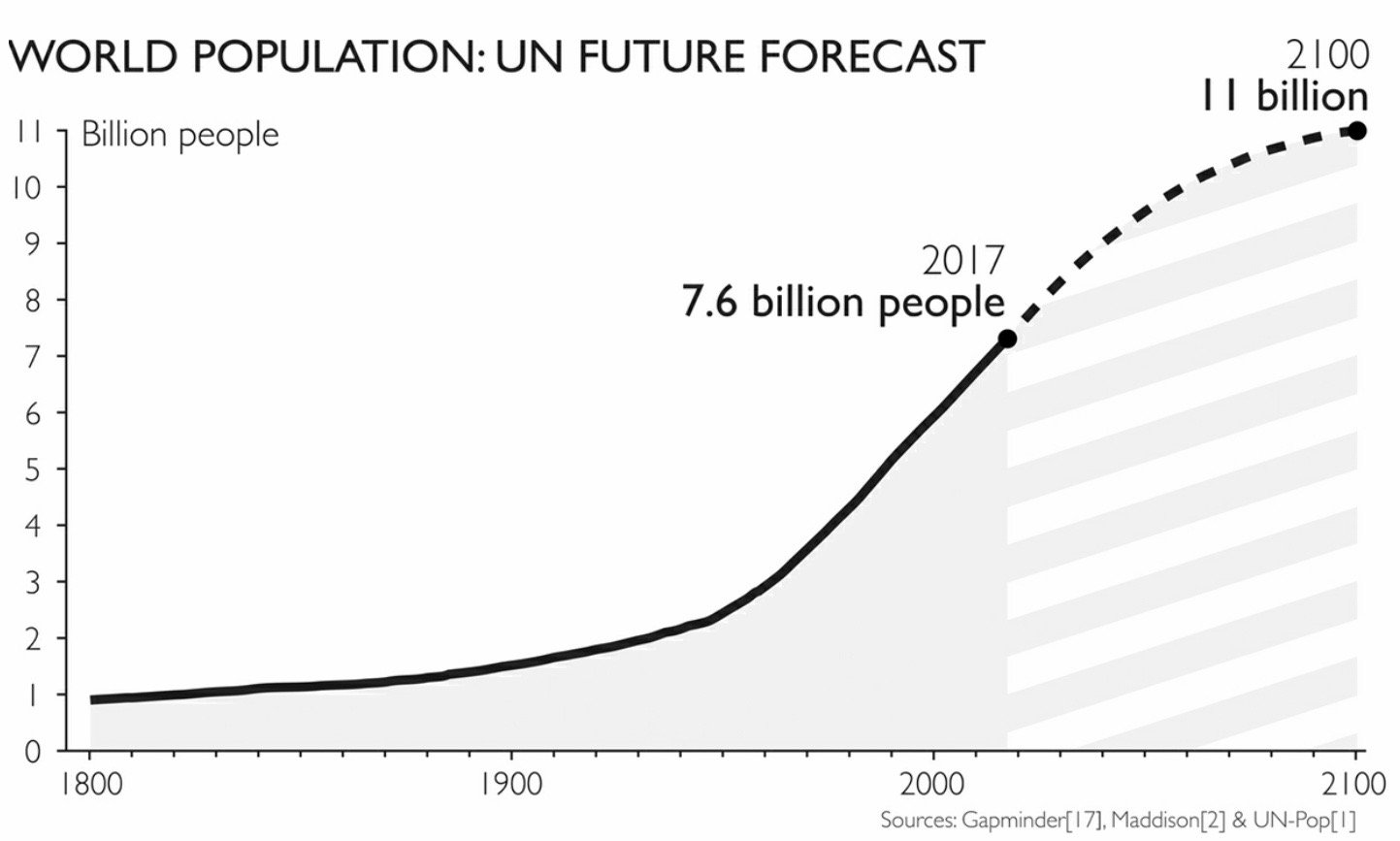

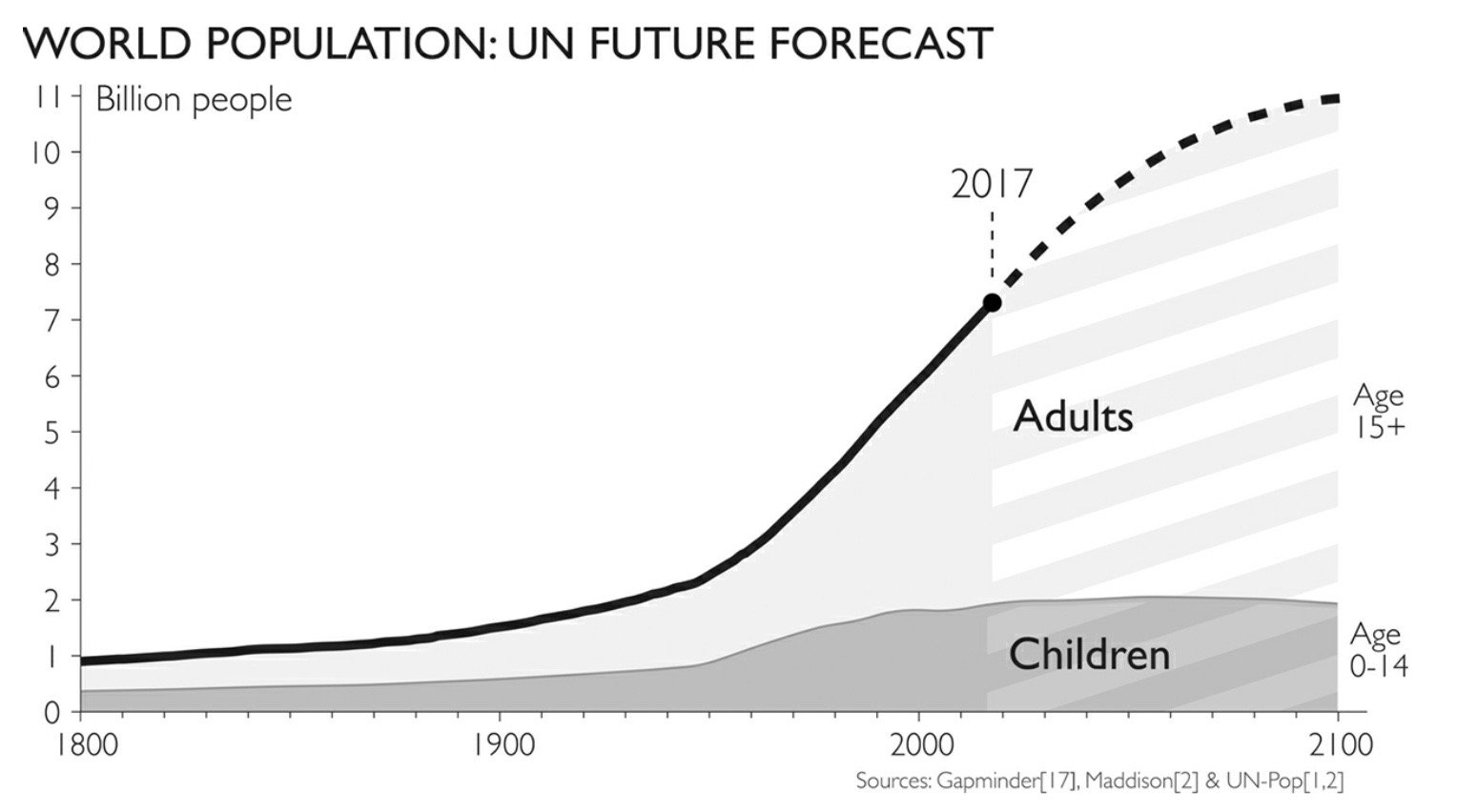

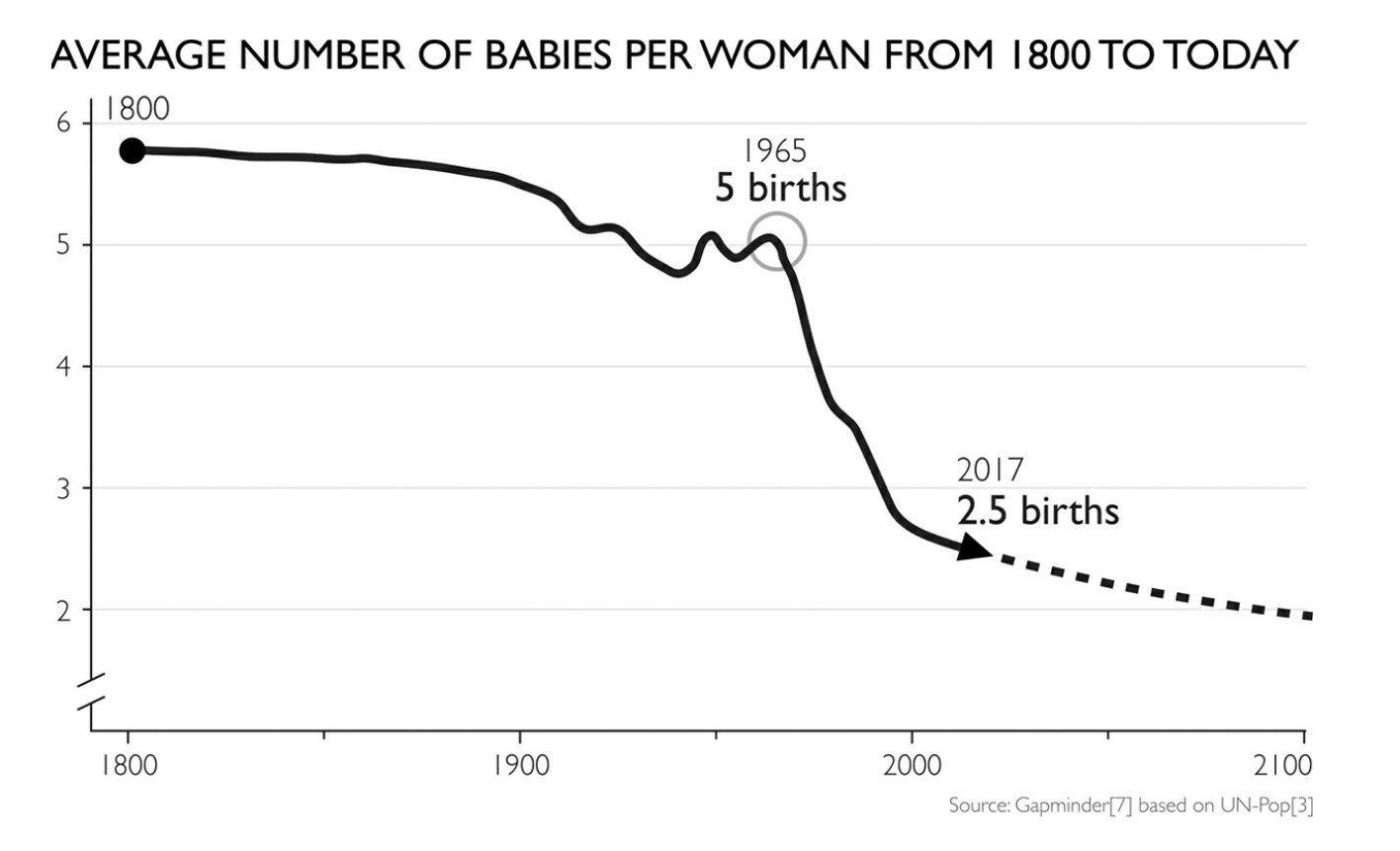

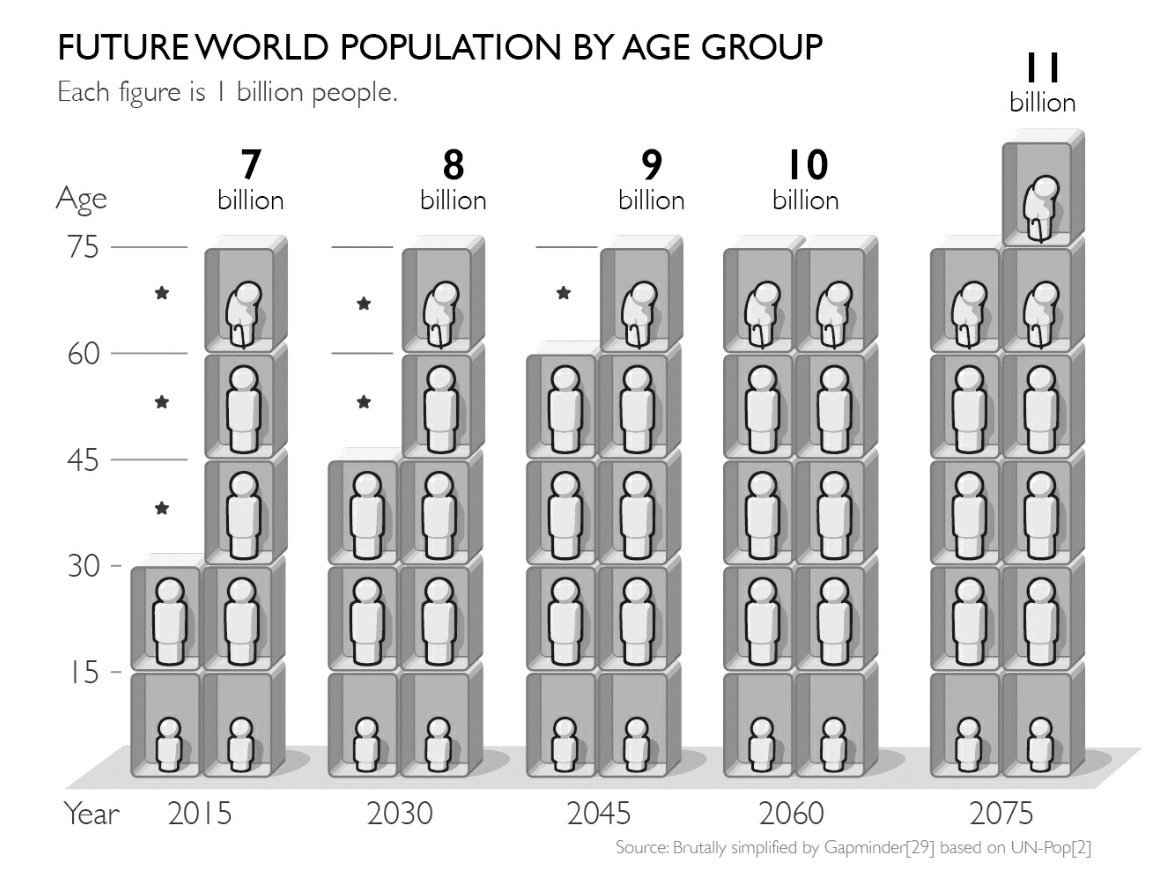

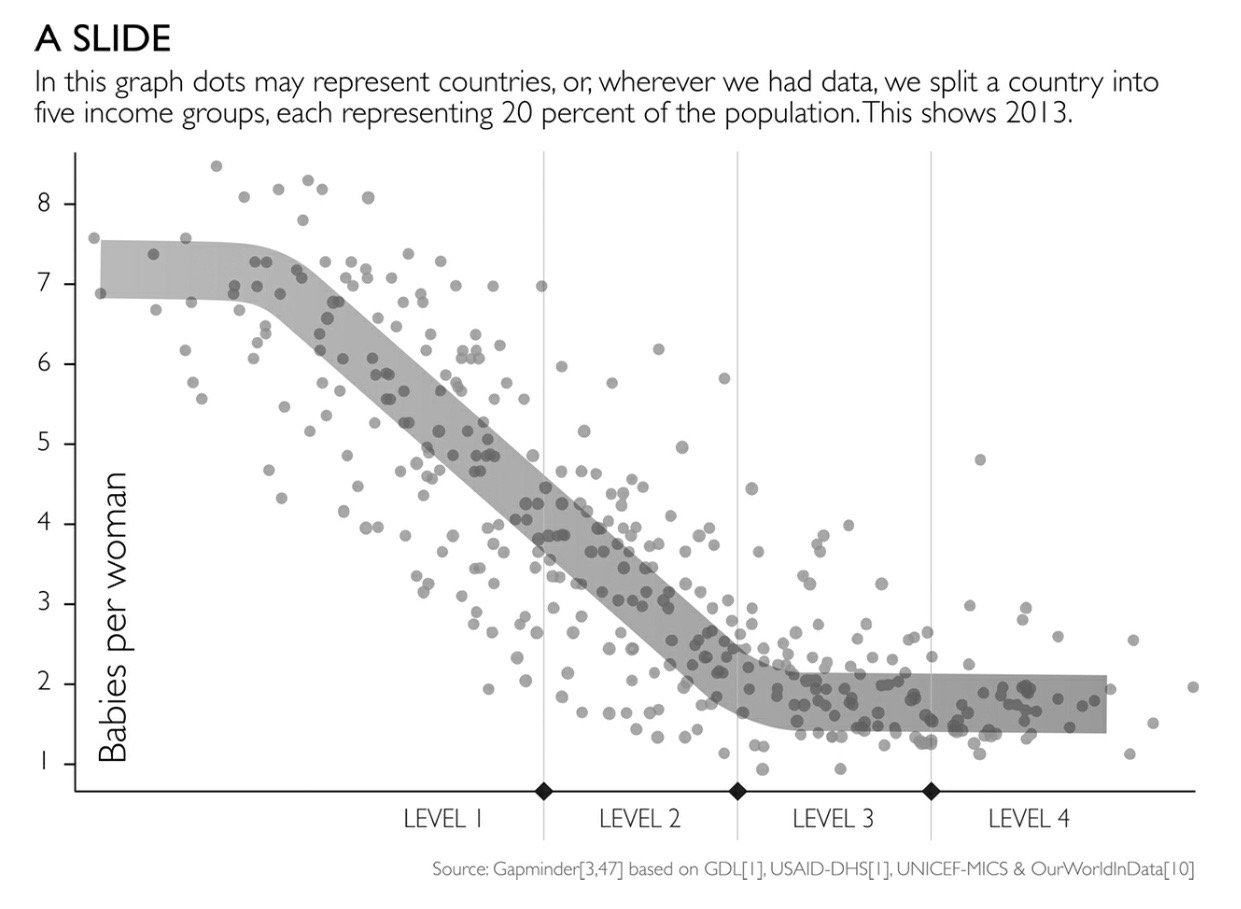

The radical change that is needed to stop rapid population growth is that the number of children stops growing. And that is already happening.

The dramatic drop in babies per woman is expected to continue, as long as more people keep escaping extreme poverty, and more women get educated, and as access to contraceptives and sexual education keeps increasing.

“Saving poor children just increases the population” sounds correct, but the opposite is true. Delaying the escape from extreme poverty just increases the population. Every generation kept in extreme poverty will produce an even larger next generation. The only proven method for curbing population growth is to eradicate extreme poverty and give people better lives, including education and contraceptives.

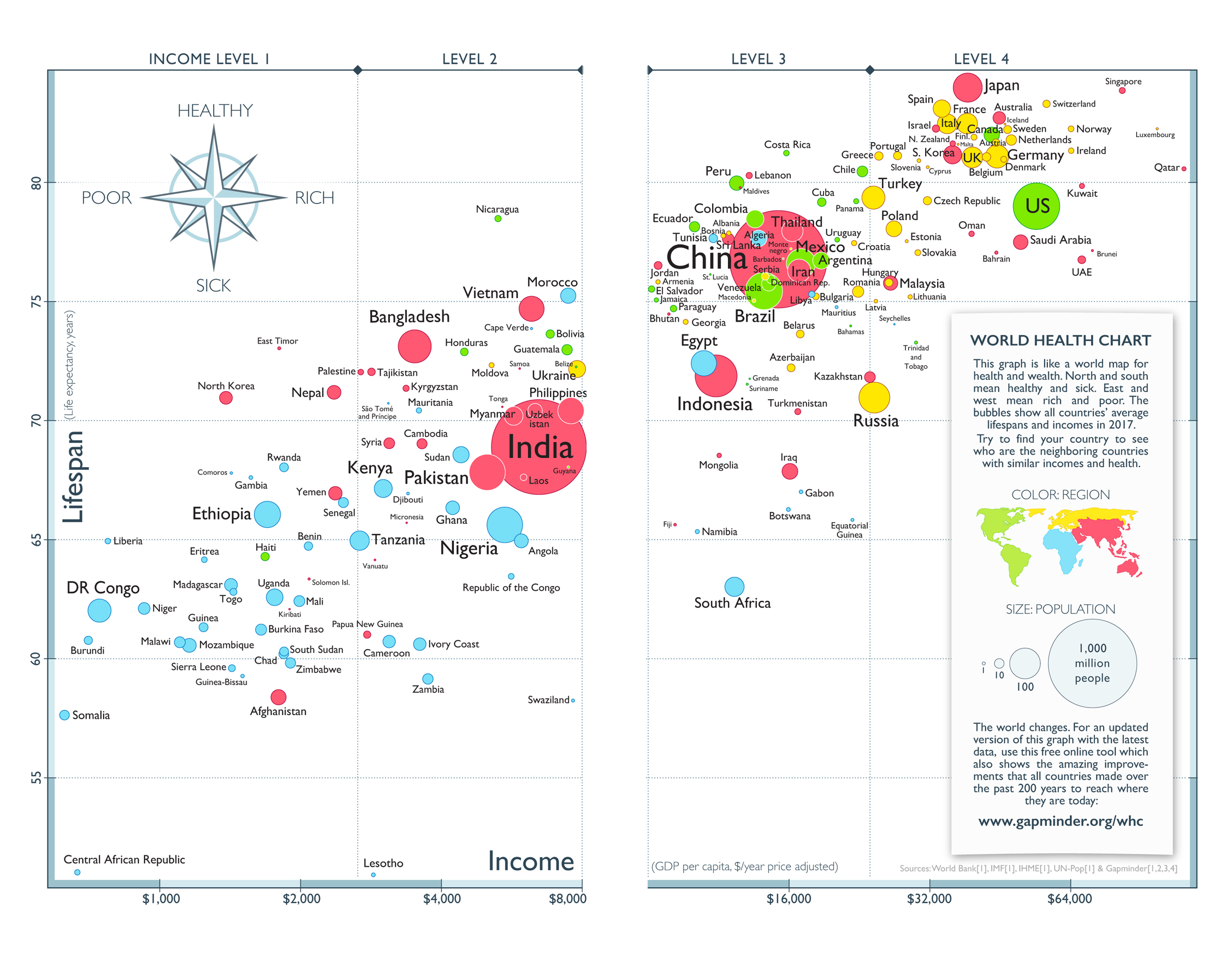

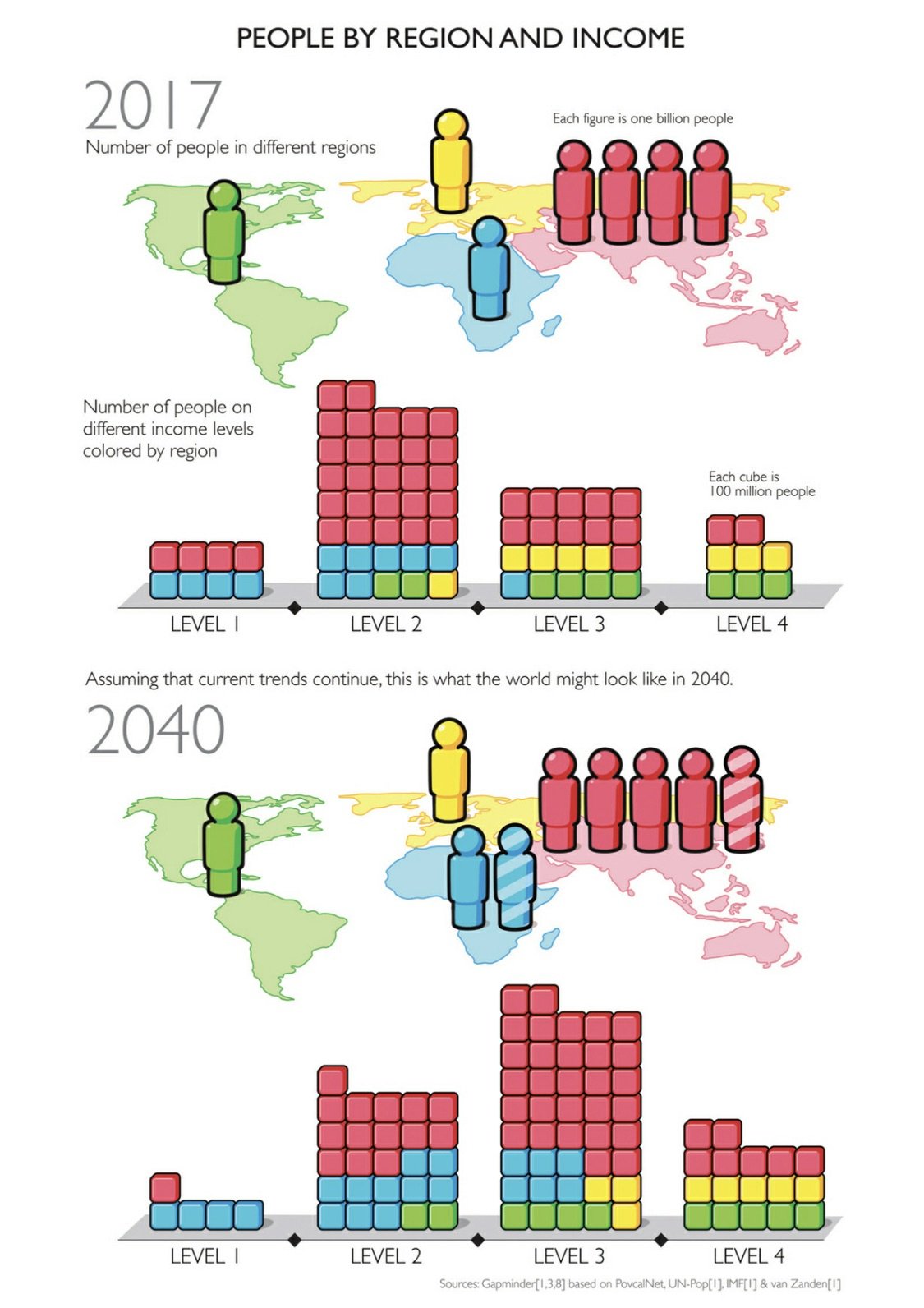

Low-income countries are much more developed than most people think. And vastly fewer people live in them. The idea of a divided world with a majority stuck in misery and deprivation is an illusion. A complete misconception. Simply wrong.

We must put our efforts into inventing new technologies that will enable 11 billion people to live the life that we should expect all of them to strive for.

__________________________________________________________________________

Factfulness in Medicine

The flu is transmitted through the air on tiny droplets. A person can enter a subway car and infect everyone in it without them touching each other, or even touching the same spot. An airborne disease like flu, with the ability to spread very fast, constitutes a greater threat to humanity than diseases like Ebola or HIV/AIDS.

Vaccination: the most cost-effective health intervention there is.

4% of Parents in the US think that vaccines are not important (Gallup). Across 67 countries, an average of 13% of people were skeptical about vaccination in general (Larson, 2016).

In a devastating example of critical thinking gone bad, highly educated, deeply caring parents avoid the vaccinations that would protect their children from killer diseases. I love critical thinking and I admire skepticism, but only within a framework that respects the evidence. So if you are skeptical about the measles vaccination, I ask you to do two things. First, make sure you know what it looks like when a child dies from measles. Most children who catch measles recover, but there is still no cure and even with the best modern medicine, one or two in every thousand will die of it. Second, ask yourself, “What kind of evidence would convince me to change my mind?” If the answer is “no evidence could ever change my mind about vaccination,” then you are putting yourself outside evidence-based rationality, outside the very critical thinking that first brought you to this point. In that case, to be consistent in your skepticism about science, next time you have an operation please ask your surgeon not to bother washing her hands.

Ebola outbreaks are defeated by contact tracers, who depend on people honestly disclosing everybody they have touched.

Almost all the increases in child survival is achieved through preventive measures outside hospitals by local nurses, midwives, and well-educated parents. Especially mothers: the data shows that half the increase in child survival in the world happens because the mothers can read and write. More children now survive because they don’t get ill in the first place. Trained midwives assist their mothers during pregnancy and delivery. Nurses immunize them. They have enough food, their parents keep them warm and clean, people around them wash their hands, and their mothers can read the instructions on that jar of pills. So if you are investing money to improve health on Level 1 or 2, you should put it into primary schools, nurse education, and vaccinations. Big impressive-looking hospitals can wait.

__________________________________________________________________________

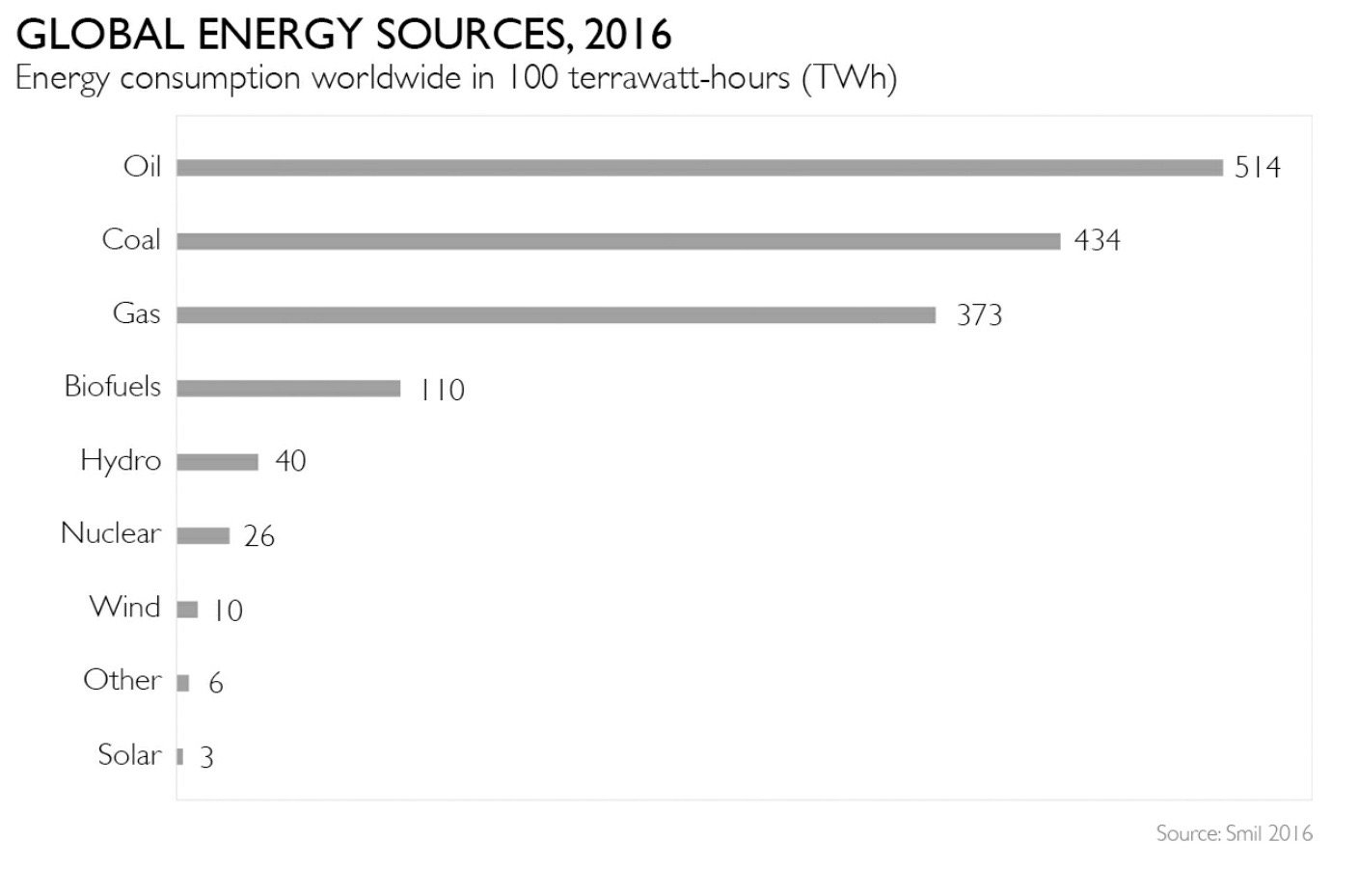

Factfulness in Environmental Sciences

The planet’s common resources, like the atmosphere, can only be governed by a globally respected authority, in a peaceful world abiding by global standards.

The large numbers—total emissions per nation—needed to be divided by the population of each country to give meaningful and comparable measures. Whether measuring HIV, GDP, mobile phone sales, internet users, or CO2 emissions, a per capita measurement—i.e., a rate per person—will almost always be more meaningful.

By the year 1900, 0.03% of the Earth’s land surface was protected. By 1930 it was 0.2%. Slowly, slowly, decade by decade, one forest at a time, the number climbed. The annual increase was absolutely tiny, almost imperceptible. Today a stunning 15% of the Earth’s surface is protected, and the number is still climbing.

Most of the human-emitted CO2 accumulated in the atmosphere was emitted over the last 50 years by countries that are now on Level 4.

Expecting developing nations to voluntarily slow down their economic growth is absolutely unrealistic. They want washing machines, electric lights, decent sewage systems, a fridge to store food, glasses if they have poor eyesight, insulin if they have diabetes, and transport to go on vacation with their families just as much as you and I do.

__________________________________________________________________________

Factfulness in War

Young men desperate for food and work, and with nothing to lose, tend to be more willing to join brutal guerrilla movements. It’s a vicious circle: poverty leads to civil war, and civil war leads to poverty.

__________________________________________________________________________

Factfulness in Economics & Politics

In order for this planet to have financial stability, peace, and protected natural resources, there’s one thing we can’t do without, and that’s international collaboration, based on a shared and fact-based understanding of the world. The current lack of knowledge about the world is therefore the most concerning problem of all.

As with most discussions about the private versus the public sector, the answer is not either/or. It is case-by-case, and it is both. The challenge is to find the right balance between regulation and freedom.

Start simply by asking what the most important facts in your organization are and how many people know them.

Incorrect Perspectives:

The seemingly reasonable but actually bizarre idea that a central government can solve all its people’s problems.

The seemingly reasonable but actually bizarre idea that the market can solve all a nation’s problems.

__________________________________________________________________________

Terminology

Chemophobia: Public fear of chemical contamination that almost resembles paranoia.

Extreme Poverty: daily income <$1.9/day.

Possibilist: someone who neither hopes without reason, nor fears without reason.

Reductionism: The (bad) habit of reducing all problems to one single problem.

__________________________________________________________________________

Resources/Links

MITs Developing Nation Diversification Tool: https://atlas.media.mit.edu/en/

UNHCR Population Statistics (Fact-based picture of global migration and refugees): http://popstats.unhcr.org/en/overview

Two different approaches for fixing the news problem: https://constructiveinstitute.org and https://www.wikitribune.com/.

www.gapminder.org/teach: free teaching materials for teachers promoting a fact-based worldview.

__________________________________________________________________________

Misc Quotes

“No one pretends that democracy is perfect or all-wise. Indeed it has been said that democracy is the worst form of Government except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time.”-Winston Churchill.

__________________________________________________________________________

Chronology

2006: The WHO reviewed all the evidence into DDT and, like the CDC, classified DDT as “mildly harmful” to humans, stating that it had more health benefits than drawbacks in many situations.-Factfulness by Rosling.

2002: The CDC publishes a 497-page document named Toxicological Profile for DDT, DDE and DDD, labeling them as “mildly harmful.”-Factfulness by Rosling.

2001: A European Council Directive is passed telling member states how to combat illegal immigration; every airline or ferry company that brings a person without proper documents into Europe must pay all the costs of returning that person to their country of origin. Of course the directive also says that it doesn’t apply to refugees who want to come to Europe based on their rights to asylum under the Geneva Convention, only to illegal immigrants. But that claim is meaningless. Because how should someone at the check-in desk at an airline be able to work out in 45 seconds whether someone is a refugee or is not a refugee according to the Geneva Convention? Something that would take the embassy at least eight months? It is impossible. So the practical effect of the reasonable-sounding directive is that commercial airlines will not let anyone board without a visa. And getting a visa is nearly impossible because the European embassies in Turkey and Libya do not have the resources to process the applications. Refugees from Syria, with the theoretical right to enter Europe under the Geneva Convention, are therefore in practice completely unable to travel by air and so must come over the sea.-Factfulness by Rosling.

10 Sep, 1998: The International Treaty against Pesticides including DDT is signed by 158 countries.-Factfulness by Rosling.

Late, 1991: Poor farmers in the tobacco-growing province of Pinar del Río started to go color blind and experience neurological problems with a loss of feeling in the arms and legs. Cuban epidemiologists investigated and sought outside help.-Factfulness by Rosling.

1962: “Silent Spring” is published by Rachel Carson; which raises concerns over the bioaccumulation of DDT. The book starts the modern environmental movement.-Factfulness by Rosling.

1960: The Chinese harvest was smaller than planned because of a bad season combined with poor governmental advice about how to grow crops more effectively. The local governments didn’t want to show bad results, so they took all the food and sent it to the central government. There was no food left. One year later the shocked inspectors were delivering eyewitness reports of cannibalism and dead bodies along roads. The government denied that its central planning had failed, and the catastrophe was kept secret by the Chinese government for 36 years. It wasn’t described in English to the outside world until 1996.-Factfulness by Rosling.

__________________________________________________________________________