Restoring Paradise by Cabin

Ref: Robert Cabin (2013). Restoring Paradise: Rethinking and Rebuilding Nature in Hawaii. Latitude 20.

________________________________________________________

Summary

Key Takeaways

Ecological Recovery is a gruesome business (killing ungulates and using chemical warfare to kill species).

Photos and designing control methods to show differences are instrumental to public perception.

Get the public involved. Write things at the level that anyone can understand them.

The solutions are there. Implement them.

We seem determined these days to trammel our existing natural areas as fast as possible.

Given our often pathetically limited knowledge and resources, which species and ecosystems should we focus on? What should we do to them, and who gets to decide? What role should science play in on-the-ground conservation? Why do so many seemingly like-minded people within the conservation and scientific communities often disagree with each other so passionately? How do we get more of the general public to care about ecology and conservation? Not only do we have to figure out how to, say, shoot animals a and b, poison plants c and d, and reintroduce species e and f back into the wild, but we must also develop and defend a coherent intellectual rationale for why we want to do these often costly and controversial things in the first place.

The conservation success stories I tell in this book revolve around these kinds of complex ecological restoration programs.

The most universal problems faced by conservationists in general: Which problems must be addressed immediately, which can be ignored for the time being, and which might eventually take care of themselves?

Because we’ve mucked it up, we have a moral obligation to try and fix things. So we analyze the situation, formulate our strategy, make some tough decisions, present and defend our logic, and get to work—you just have to start somewhere and give it your best shot. Along the way we’ve learned to accept the fact that we may be wrong, so we monitor ourselves as objectively as possible and remain ready to change and adapt as necessary.

Part 1: I tell the in-depth story of the Hakalau Forest National Wildlife Refuge’s ongoing efforts to restore thousands of acres of degraded pastures on the island of Hawai‘i

Part 2: I tell three shorter stories from three different islands.

Kill and Restore: Highlights the US Park Service’s efforts to control alien species and reestablish native species and ecosystems within their vast Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park on the island of Hawai‘i.

Pū‘olē‘olē Blows: Follows one charismatic scientist’s efforts to restore an ecologically and culturally important forest on the island of Maui that most experts believed was unrestorable.

Turning Hands: Tells the story of the biocultural restoration of a thousand-year-old taro plantation at the Limahuli branch of the National Tropical Botanical Garden on the island of Kaua‘i.

Part 3: I consider multiple perspectives in the conservationist field of ecological restoration.

________________________________________________________

Introduction

There are ~ 12K extant Hawaiian species unique to the archipelago.

48 of 59 endangered species listed by the Obama admin in the past 2y have been Hawaiian plants and birds.

Hawaiian History may be divided into three periods:

Prehuman: Before the first humans reached these islands 1500-1800 years ago. Most of the islands were densely forested all the way down to the shore.

Prehistoric: From the time the first people landed in Hawai‘i until westerners arrived in 1778.

These first human settlers made numerous back-and-forth journeys between Hawai‘i and their ancestral Polynesian islands. On the return voyages they brought back their most important animals, such as dogs, pigs, chickens, and the Polynesian rat.

Paleontologists estimate that >2K species of land birds (about 20% of all the bird species described for the entire planet!) have become extinct since humans colonized the Pacific Islands.

Modern: 1778 to the present.

________________________________________________________

Part 1 If you Plant it, Will they Come?

________________________________________________________

1 JOURNEY TO HAKALAU

Hawai‘i’s rain forests are dominated by just two types of canopy trees: ‘ōhi‘a lehua (Metrosideros polymorpha) and koa (Acacia koa).

Speciation within the Hawaiian Islands far exceeds the rate at which new species immigrated to the archipelago.

<2% of Hawai‘i’s flowering plants appear to have dispersed here by air; seeds carried by birds account for nearly 75% of the successful colonization’s, and another 23% probably got to Hawai‘i by direct flotation or rafting on floating debris.

Hawai‘i’s terrestrial native biota is both depauperate (species poor) and disharmonic (weird).

The absence of specialized insect pollinators makes sexual reproduction impossible for the great majority of orchid species, which also probably explains why Hawai‘i has no native fig or banyan species.

Evolution in Hawaii has led to ~70 land birds, 5K insects, ~1K flowering plants, and 800 species of snails found nowhere else in the world.

________________________________________________________

2 PLACES OF MANY PERCHES AND HOOVES

Hakalau: ‘Place of many perches (Hawaiian);’ a Forest Refuge in Hawaii.

Hakalau provides a critical habitat for 14 species of native birds, 29 rare plants, and the state’s only native mammal, the endangered Hawaiian hoary bat.

Today the best mesic forests at Hakalau are primarily found in the areas where cattle grazing was restricted by rugged topography, a protective underlying substrate of jagged ‘a‘ā lava, or both.

The primary biological sources of ecological degradation at Hakalau are ungulates and weeds.

Ungulates: Destroy Vegetation while facilitating the establishment of weeds by dispersing their seeds; requires fencing and/or eradication.

End, 1997: Construction of 44 miles of fencing is completed (at a cost of $1,243,627) creating eight separate exclosures that span the entire upper elevation portion of the refuge. With about a 100 more miles of fencing needed to finish protecting the forest bird habitat, funding runs out.

1997: Hakalau grows by 5K acres through the purchase of the Kona refuge.

1995: Hakalau Refuge pig and feral cattle hunting is stopped by the USFWS.

1991: Hakalau Refuge adopts a “Sport Hunting Plan” that calls for using public pig hunting as an ungulate control strategy within selected areas.

1985: Hakalau (Hawaiian- ‘place of many perches’) Forest Refuge is created following the purchase of two parcels of ranchland totaling 8313 acres.

________________________________________________________

3 SCIENCE TO THE RESCUE?

Unlike mainland tropical forests, where the greatest plant diversity is found in the tree canopies, most of the diversity in Hawaiian rain forests resides on or near the ground, perhaps because there has not been sufficient time on these young islands for a rich tree flora to evolve.

Over the years in which tree vegetation had been repeatedly browsed back, (trees) apparently developed extensive root systems capable of supporting rapid above-ground growth.

Nurse Log Experiment: Why were decaying logs so advantageous for native plant establishment?

In contrast to the regenerating natives clinging to those decaying logs like lifeboats, the grasses and other weeds tended to be rooting almost everywhere except the logs. These observations led me to wonder whether it might be possible to facilitate the restoration of the refuge’s pastures by manipulating their substrates so that they favored the “natural” establishment of native species.

I settled on two overarching goals for my Hakalau research program:

Provide concrete, feasible tools and ideas to help preserve and restore native species.

Produce high-quality research publications that significantly contribute to our basic scientific knowledge.

The general question I chose to investigate was whether the conditions favoring the germination and establishment of native rain forest species might be different than those favoring alien species.

________________________________________________________

4 LAULIMA

“When the final scientific papers and reports come back to us, they are almost always focused on one or a few species. Often, they are quite interesting, but because we are managing the refuge for the ecosystem as a whole, they’re worthless as far as management recommendations. And the theoretical stuff is nice on a small scale, but as soon as you go to a larger scale … For us, it has just been a lot of seat-of-the-pants experimentation and learning as we go.”-Hakalau Management.

The Hakalau Management Plan explicitly employed a philosophy of “let’s see what works, what doesn’t, and revise accordingly.” Their overarching goal was obviously to reforest the refuge’s vast upper-elevation degraded pastures and reconnect them to the relatively intact lower-elevation rain forests.

Koa Trees: Hawaiian Forest Engineers; their canopies provide protection enabling the establishment of other native forest plants in exposed pastures.

Managers discovered that if they grew koa in long, narrow dibble tubes instead of pots and ran a bulldozer mounted with a three- pronged scraping rake across the planting areas, crews could plant >2K trees a day.

Two major challenges to the Koa were frost and drought.

Frost: After extensive observation, monitoring, and analysis, managers concluded that frost was killing or at least weakening most of the koa trees that failed to establish and thrive.

A team of scientists concluded that outplanted koa seedlings could survive a moderate amount of frost, but if they defrosted too quickly their cell walls could rupture and desiccate. Thus, it appeared that the makai shade cloth treatment was saving the koa in part by blocking the morning sun and slowing down this warming process in addition to blocking out about half of their exposure to the cold night sky and keeping them 1-2 degrees warmer by reflecting some heat off the ground.

________________________________________________________

5 PLACE OF MANY NEW PERCHES AND FEWER HOOVES

Common mistakes in conservation biology and resource management:

Investigating too many variables that are too difficult to standardize and control.

Becoming increasingly disconnected from the nuances of one’s own experiments when shifting from field ecologist/restoration practitioner to manager/bureaucrat.

Workaholism.

Koa Trees

We’ve found that just about anything we plant under the koa corridors will survive.

As the koa matured and created more shade and organic litter, these plants can create the little nongrass kīpuka observed elsewhere on the refuge, and the birds would disperse the seeds and accelerate the native plant expansion.

My feeling is this is not the final stage; this is not the final forest. In the future, when we’ve got the canopy, then the other trees will start filling in, and then we can get the normal, natural form.

Eventually we are going to end up with little islands of protected areas within these islands. I hope they aren’t too small, and I hope we will have some sea-to-mountaintop ahupua‘a [a Hawaiian land division system somewhat similar to our modern concept of ecological watersheds] that are managed for native species on all the Hawaiian Islands. Whether or not that happens will ultimately depend on the public—we’ve seen in the past just how quickly the politics and the pendulum can change.

________________________________________________________

Part 2 Restoration Roundup

________________________________________________________

6 KILL AND RESTORE Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park

Hawaii Volcanoes NP is a model for how effective ecological restoration can be when the necessary political will, resources, expertise, and dedication all come together.

The primary biological sources of ecological degradation at Volcanoes are goats, cattle, and weeds.

Ecological recovery of relatively intact forests following the removal of pigs was generally rapid and substantial.

Although their goat, pig, and other ungulate eradication efforts were all extremely difficult, laborious, and expensive, they were a relative breeze compared to the challenge of controlling the park’s alien plant populations.

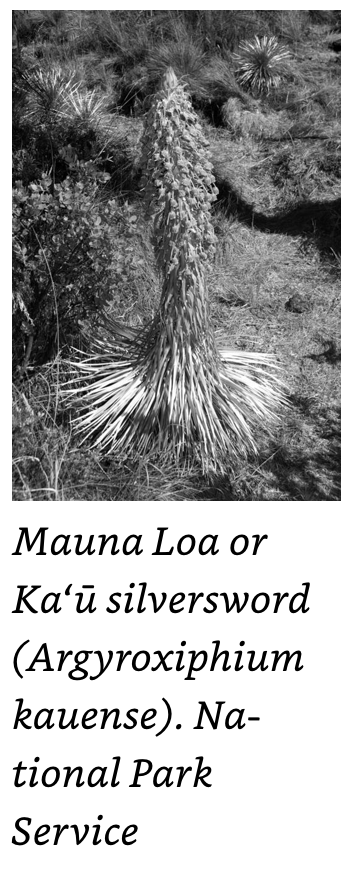

Four charismatic flagship species: the nēnē goose, the hawksbill sea turtle, the dark-rumped petrel, and the Mauna Loa silversword.

Extensive research has since revealed that the major factors limiting turtle nesting and hatchling success appear to be mongoose predation and hatchling stranding’s due to altered beach conditions, disruptive human activities such as fishing, beach vehicles, and artificial lights, and the establishment of alien plants.

________________________________________________________

7 THE PŪ‘OLĒ‘OLĒ BLOWS

Auwahi: A 5,400-acre subsection of the SW rift of the Haleakalā Volcano on E Maui at an elevation of 3K-5K’.

The famous botanist Joseph Rock identified the remnant dry forests at Auwahi and North Kona on the Big Island as the two botanically richest regions in the entire territory of Hawai‘i.

________________________________________________________

8 TURNING HANDS Limahuli Botanical Garden, Kaua‘i

Limahuli (Lima- hand + huli- turn over or search): The “named wind” that ricochets around Limahuli, turning and tumbling its vegetation like a “probing hand.”

We hoped our results could help them answer a series of basic yet critically important questions:

How much of the alien overstory and understory should be removed at one time?

What kinds of natural recruitment of native and alien plants will occur within each of the different vegetation removal combinations?

Which native species should we plant in there, which can be established by direct seeding, and what is the best microenvironment for each of them?

Which weeds should we go after aggressively, and which can we safely ignore?

Scientific knowledge is obviously important, and maybe down the road some day, when our program is further developed, we’ll be able to do and utilize more of it, but right now it’s really just practical experience. We do very little monitoring or data collection, unless we have to provide some formal documentation to a granting agency, because we’re always just scrambling to get the work done.

There’s nothing like success to create more success.

________________________________________________________

Part 3 Herding Cats with Leaf Blowers

________________________________________________________

9 MULTIPLE PERSPECTIVES

Question 1: Why do you care about biodiversity in general and Hawai‘i’s native species and ecosystems in particular, and what motivates you to try to preserve and restore them?

“Many of the people I spoke with (as is the case with environmentalists in general) said that their interest in and concern for biodiversity had grown out of their childhood love of nature and the outdoors.”

Question 2: What is your restoration philosophy?

Do people see themselves as purists (proceed cautiously, strive for historical accuracy when reestablishing native species and their communities, and so on), pragmatists (proceed rapidly and get over the fallacy of historical accuracy), or somewhere in between?

I found no consistent relationships between people’s conservation philosophies and their experience, occupation, employer, education, or expertise.

“You have to spend a lot of time walking around the place to get a deeper idea of its community structure, then patiently design a plan that takes into account fine-scale processes like moisture, substrate, nutrient and disturbance gradients, locally adapted gene complexes, biogeography, and evolution.”

“We should start by working at small scales in relatively simple systems with a lot of thought and concept building and figure out how to do it right before we attempt to work in more complex systems and at larger spatial scales.”

“The Hippocratic oath of ecological restoration? I don’t buy it one bit—of course we’re going to do harm! We’ve got to quit being such weenies, quit waiting for some new scientific study or new tool to tell us what to do and save us—we need to roll up our sleeves and get to work now!”

“All this obsession with genetics—PLEASE! That’s the ultimate fallacy, and it demonstrates how far off academia is from the rest of the real world. They’re worried about hybridizing related species and contaminating the gene pool? If we’ve learned anything about Hawaiian evolution, it’s that these species are rampant with hybridization, and they’re still doing it right now in front of our eyes.”

“I’ve also come to see that plant communities are not comprised of any fixed, magical combination of species—they’re not necessarily coevolved or “balanced,” and they can survive and evolve with new players like some of the less obnoxious weeds and plants brought over by the Polynesians.”

“When I first came out here, I was passionately idealistic because I was naive and ignorant and had no idea how bad things really were and what it takes to preserve and restore species and their ecosystems. Now I have less delusions about what this place is going to look like in 10-20y, and I just try to get a few simple little things done well and hope that maybe we’ll have a chance to revisit the big idealistic vision again a few decades from now.”

“When we reach some crossroads where a difficult decision has to be made and we just can’t agree, maybe there are times when we should just vote and move on with no hard feelings. Most people can only take so many hours of sitting around talking in circles and arguing anyway, and too much of that tends to frustrate and demoralize the more action-oriented folks.”

Question Three: What do you think are the most important things we should do to preserve and restore Hawai‘i’s natural environment?

“Save the best places first.”

“I don’t believe in the idea of wilderness anymore—the separation of humans and nature is an artificial and divisive concept.”

“Most of society doesn’t get and can’t embrace the big conservation picture, and thus they can’t understand the concept that everything is connected. So we should start by working in their neighborhoods and helping people see what’s going on back there, but we do the exact opposite by focusing almost exclusively on the remote, pristine areas. Then we tell them that those areas are so precious and fragile that nobody should ever go there except us—no wonder conservation isn’t getting anywhere!”

“You don’t educate the public, you don’t get their support, and then you wind up being unable to do the critical things we already know how to do. So we should be doing things like placing public service announcements on TV, showing a picture of a native bird while they roll the credits after the newscast: “Today’s bird is …” We should be getting our messages out to the kids on McDonald’s tray liners, and selling ‘i‘iwi ale to their parents. We have to bring the native species to life and make them stars so that the public can understand what’s happening and take some ownership.”

Question Four: What role does science presently play in guiding ecological restoration in Hawai‘i, and what if any changes would you like to see in the future?

“When the public grasps the stories about, say, the amazing paths evolution has traveled in Hawai‘i or the unique natural history of our native species, they value the natural environment and the efforts to protect and restore it that much more.”

“Managers need simple, concrete information and tools immediately, but science doesn’t work that way—it operates on a slower, one-piece-of-the-puzzle-at-a-time scale.”

“A lot of the “conservation scientists” do these tiny little experiments in which they control and rigorously measure everything. Then they publish these studies in their technical academic journals and think it’s someone else’s job to interpret their results and convert them into management practices. The truth is that neither the managers nor the policy makers have the time, training, or incentives to do that—none of these people ever even read that stuff!”

“As a resource manager, I will always sacrifice rigor, replication, data collection, et cetera, for more on-the-ground accomplishments, because that’s our mission.”

“Much of the data we do collect is really messy. There’s no continuity or consistency to it, because it’s usually collected by different people at different times using different protocols.”

“Some scientists acknowledged that their work probably had little if any applied value, but they often felt pressured to claim otherwise in their grants, publications, and oral presentations.

“I’ve yet to see a single example in which academic science and all of its theories and models directly helped someone design and implement a resource management strategy or restoration program in the real world. Funding, logistics, politics, partnerships, politics, charisma—those are the things that really drive conservation out here, not science.”

“Should we try to preserve Hawai‘i’s native biodiversity even if it turns out that we can’t scientifically show that native species are necessarily better for things like carbon cycling and watershed management? Science cannot address those kinds of questions.”

“(Academics) getting us some funding, contributing some labor towards our projects, giving nontechnical talks, and writing simple pamphlets that help the public understand and support our work—those kinds of things would really help improve our overall relationships.”

“Scientists are pressured to get external grants and produce esoteric academic publications, what they actually do is rarely solution oriented—their conclusions are almost always, “We need to do more research!”

“After I stopped doing academic scientific research and started working with farmers, the way I saw and interacted with the natural world changed drastically. I began to see that science is only one way of perceiving and understanding the world. Sure, it’s a really important and interesting perspective, but there are other equally important and interesting points of view as well.”

“The vast majority of the people in Hawai‘i, and the planet as a whole, do not and probably never will see the world through the lens of science. But if scientists don’t understand this and can’t relate to any of these other knowledge and value systems, then they and their work will remain alienated from the masses, and their brand of conservation will remain a fringe movement of elites.”

________________________________________________________

10 NATURE IS DEAD. LONG LIVE NATURE!

By the end of nature, I do not mean the end of the world. The rain will still fall and the sun shine, though differently than before. When I say ‘nature,’ I mean a certain set of human ideas about the world and our place in it. We have changed the atmosphere and thus we are changing the weather. By changing the weather, we make every spot on the earth man made and artificial.”-The End of Nature by McKibben (1989).

There are now over 7K varieties of cultivated tomatoes, none of which resembles their wild ancestor. Since all of today’s agricultural species are derived from many years of intensive, cosmopolitan breeding programs, are the seeds of a native, old-fashioned heirloom variety necessarily more natural than seeds from an exotic hybrid?

Modern environmentalists must grapple with many similar kinds of physical and philosophical paradoxes. Fundamentally different ideas about what is and is not natural—and to what extent this naturalness matters—underlie much of the tension within Hawai‘i’s conservation community in particular and the broader environmental community in general.

Conservation: A kaleidoscope of interacting species, ecosystems, people, and cultures that is fueled by a rich mixture of values, aesthetics, science, art, philosophy, ego, and shifting alliances among government agencies, private organizations, special interest groups, local communities, and charismatic individuals. It often makes a mockery out of our best attempts to tame and corral it with unifying theories, formal reductionist science, and rigid philosophical and practical frameworks.

Purists (Pure Conservation): Conservationists who believe we should focus on the preservation of relatively pristine areas and implement restoration projects with extreme caution or not at all.

Some believe in accomplishing more traditional conservation goals such as preserving native biodiversity, protecting our watersheds, or minimizing soil erosion. Some are more interested in culturally oriented projects such as creating ethnobotanically oriented “canoe gardens” that showcase the species brought to Hawai‘i by the Polynesians in their voyaging canoes.

Some stridently believe we should fight every last noxious weed and bug and never give up on any native species or ecosystem. Others argue with equal fervor that such thinking is naive, and if we don’t systematically prioritize our efforts, we are going to lose everything.

Many believe that there is no rigid boundary between people and nature, that naturalness (however defined) should not necessarily be our overarching conservation focus, or both.

Are the often highly skilled and dedicated staff members who strive to create “authentic” nature experiences in such places (as Disneyland) doing fundamentally different work than “real” conservationists?

An increasingly popular view of today’s complex mosaics of “natural” and novel ecosystems is that they are in essence a series of gardens. Some argue that restoration ecology is itself just another form of agriculture, and that its practitioners do more or less the same thing as conventional farmers and gardeners.

It’s time to embrace the aliens.

Look, I love science; it’s an essential tool. But it must be disciplined in order to be responsible, so that it also serves the land and the people. I’m not that interested in having a plump resume or advancing through the system; I’m more interested in conservation and on-the-ground accomplishments, having a hālau [“group,” or literally, “a branch from which many leaves grow”], connecting with kids, mentoring young people, building community—that’s the stuff that matters; that’s what changes the world.

________________________________________________________

Management Challenges

As is almost always the case in such restoration projects, the problems are too urgent and the risks of doing nothing too great. So, managers analyze their situation, devise the best plan they can, and spring into action.

“Wow! What if this works?” I thought about that for a minute, then said, “What if it works and no one cares?”

Primary challenges are habitat loss and degradation; noxious alien species; introduced predators; exotic diseases.

The primary biological sources of ecological degradation are ungulates and weeds. Because ungulates often facilitate the establishment of weeds by dispersing their seeds while simultaneously destroying the native vegetation, the first step toward ecological restoration in Hawai‘i is almost always ungulate control, and the first step toward ungulate control is almost always erecting a fence.

Conservationists must deal with the infinitely greater complexity of interacting living species and the seemingly intractable world of human desires.

There seems to exist an inverse relationship between the extent of peoples’ on-the-ground experience battling invasive species and their confidence in their own ability to conceptualize the problems and devise the most effective solutions.

________________________________________________________

Ungulates

Ungulates: Pigs, Goats, Cattle; destroy Vegetation while facilitating the establishment of weeds by dispersing their seeds; trample and eat native vegetation that never evolved protective mechanisms such as spines, thorns, chemical repellants, or irritants, and unpalability (particularly in large herds).

Pigs: The greatest threat to Hawai‘i’s remaining native rain forests. Pigs turn over the earth in search of worms and slugs, wallow in the mud, and knock over and trample everything in their way.

Feral pig populations can double within a single year and exceed 75/sqkm in Hawaiian rain forests.

Goats:

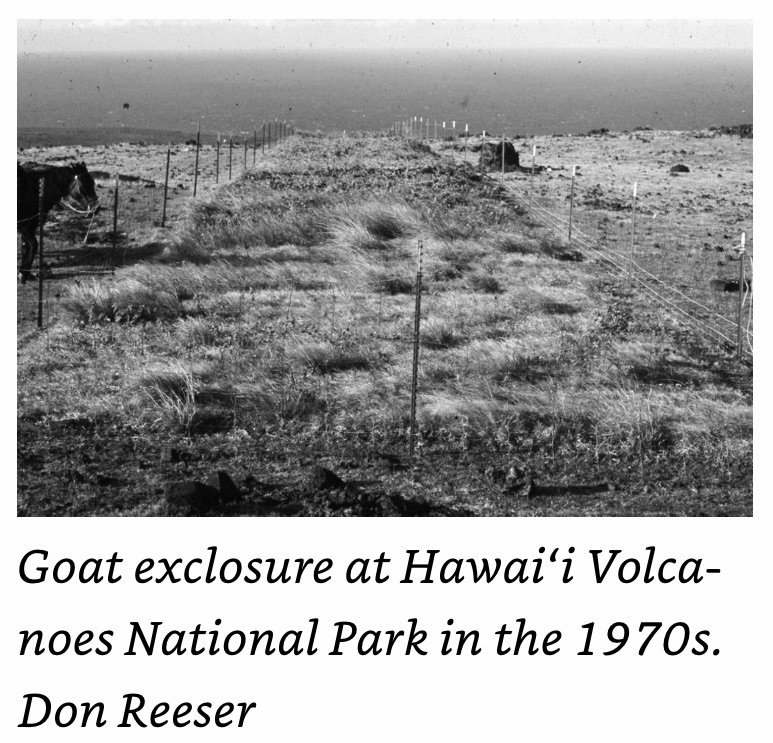

In a 1972 report, managers summarized the results of the first goat exclosures and other complementary studies within the park by drawing six “startling conclusions”:

Goats are selective and choose native species over nonnative species whenever available.

Goats help to perpetuate the growth and spread of less palatable exotic species.

Goats can, in time, deteriorate a native forest into a grassland-savannah.

Goats are the likely cause of extinction, or near extinction, of several species of soft-barked native trees and shrubs.

Goats denude areas of their vegetative cover to a point that causes shallow topsoils to erode, exposing rocky substrates.

If goats can be removed from the scene, native plants will reappear, flourish, and in some cases out-compete invading exotics.

Drives and hunts were only effective in keeping the goat population young, healthy, and vigorously reproductive.

Many Park Service staff and research scientists in those days believed that the goat and cattle damage was so severe that it was probably irreversible, and that these ungulates should in fact be retained as “a necessary evil” to control the ever-worsening alien plant invasions and to reduce the risk of wildfires by browsing down the exotic grasses that dominated many of the drier sections of the park.

Ungulate Control Techniques:

Subdivide, Fence, and Eradicate (aka Divide and Conquer): fenced management units and intensive and coordinated professional hunts

To flush out and kill the last few goats in the most remote and rugged areas, managers utilized a combination of discreetly executed helicopter hunts and radio-collared “Judas Goats.”

Standard dog-hunting, snaring, and trapping techniques.

Manage the degraded areas for game animals and hunting and reduce or eradicate the ungulates within the best remaining native ecosystems.

________________________________________________________

Invasive Plants & Weeds

Invasive Species produce enormous numbers of long-lived seeds that can rapidly germinate and establish following fires.

One thing we’ve consistently found that doesn’t work is trying to direct-seed our plants in the field.

Gorse: A fast growing invasive thorny shrub.

Gorse Control: Biological, chemical, and mechanical control programs, intensive sheep and goat grazing, controlled burns, and reforestation. Biocontrol agents include a web-building spider mite, seed-eating weevil, soft-shoot moth, and rust-inducing fungus.

Alien Plant Crews: Minimize and mitigate alien plant disturbances, map and monitor the most important weeds, deploy manual, mechanical, and chemical control techniques against selected weeds in strategic areas, participate in interagency partnerships to control potentially invasive new species, strive to improve their ecological understanding of key alien plants, and work with other agencies and individuals to develop new and improved weed control tools.

Biocontrol: The art and science of using one or more deliberately introduced alien species to control the distribution and abundance of another problematic alien species. The theory behind this fight-fire-with-fire approach is that species are often limited in their home countries by other coevolved native species such as predators, herbivores, and pathogens. Biocontrol practitioners thus attempt to find these kinds of species from the target alien’s place of origin and import them to the nonnative countries where it is causing problems.

There are infamous examples of biocontrol backfire in the Hawaiian Islands such as the introduction of mongooses (to control rodents) and rosy cannibal snails (to control the giant African snails); in both cases, these exotic species failed to control their targets and became noxious pests themselves.

It often requires well over $1M dollars and a decade of research to release a single biocontrol agent.

To date there have been no unequivocal biological control success stories in Hawai‘i.

________________________________________________________

Temperature

Frost: After extensive observation, monitoring, and analysis, managers concluded that frost was killing or at least weakening most of the koa trees that failed to establish and thrive. Managers tried over a dozen different frost-protection devices:

Mulching with rocks: Absorbs heat during the day and releases it back to the trees during the cold night.

Wall-O-Water: A commercial product used to protect tomatoes.

Mini-greenhouses: Absorbs Heat.

Makai Shade Cloth: Blocks the morning sun and slows down the warming process to slow the defrosting of trees in the morning sun which can rupture and desiccate cell walls. They also block some exposure to the night sky and keep them 1-2 degrees warmer by reflecting heat off the ground.

________________________________________________________

Workload & Funding

Every time we clear and plant another acre, we generate that much more ongoing maintenance that can’t be neglected just because someone gave us money to start something else.

Managers lack a source of permanent funding.

The two most important factors limiting restoration programs are simply money and time.

One potential solution to the perpetual money and personnel problems is to create a volunteer program.

I started to feel like I was back in the federal system, where we had to lay everything out ahead of time, even though there was almost always a night-and-day difference between what was on paper and what actually happened.

________________________________________________________

Management Strategies

First, learn how to repair the ecological fabric, then progressively start isolating the factors to figure out what’s limiting when things fail: Is it rats? Pollinators? Seed dispersers? Genetics? Then we start ramping up what we learn in places like this to a landscape scale.

Despite their diversity and complexity, most large-scale restoration projects can be broken down into three major, often intertwined management goals:

Remove or mitigate the source or sources responsible for the past and present ecological degradation.

Facilitate the recovery and establishment of the most important target species.

Carefully monitor what happens and refine the management activities accordingly.

Restoration is really more of an art than a science.

Implement some of the effective yet underutilized management strategies we already have.

A major goal is simply to slow the rate of ecological degradation and hold the line until new scientific discoveries enable us to accomplish things we can’t even imagine today.

The closest scientists have ever come to waving a magic wand at large-scale ecological problems was probably releasing a few miraculously successful biological control agents.

Managers usually start by simply looking at which if any natives are already there, then try to collect, propagate, and outplant them back into the field if and when they can. They also ask experienced field botanists what they think could and should grow in their different sites and rely on their own observations of what has and has not worked previously.

Start telling other people about your work, share the responsibility. When we reach the tipping point of enough people with firsthand knowledge getting involved, people who have seen with their own eyes and done with their own hands, really good things can happen.

Trust the balance that emerges from the process of re-establishing regimes of competition among native species.

There are so many interacting factors that are virtually impossible to track and tease apart and comprehend, I guess I’ve just learned to accept the limitations of our knowledge and believe that in the end, the mountain knows best.

Solving the ecological problems is actually less difficult than solving the human problem: Successful conservation requires more than good science and hard work. It requires a strong human presence.

________________________________________________________

Science & Policy

What does “science-based” actually mean? Proceeding in a logical, deliberate, and methodical manner? Utilizing “objective” evidence? Collecting lots of quantitative data to test and refine a series of hypotheses? Relying on the expertise and judgments of scientists and other highly trained and educated professionals? The reality is that highly trained and educated scientists and other professionals who employ all of these techniques often reach radically different conclusions.

ESP: Even if we ever developed a potent arsenal of conceptual or technical silver bullets, we would still have to grapple with our radically different philosophies about such fundamentally important underlying issues as the human/nature relationship.

Science is not the right tool when the relevant questions and variables are not technical or quantifiable, and even when they are, science by itself cannot tell us what to do.

Many nonscientists—and even some scientists themselves—do not realize just how diverse and divided the scientific community often is. We are informed and motivated by a complex mixture of rationality, emotion, altruism, selfishness, ego, ideology, and aesthetics.

Education: People’s level of interest in and appreciation of nonshowy species appears to be proportional to their prior botanical knowledge and general ecological education.

Prediction: Research has repeatedly demonstrated that the predictions of credentialed professionals are no better than those made by the general public.

Expertise: Studies show that expertise and experience does not make one better at interpreting scientific data.

There appears to be an overall inverse relationship between the accuracy of an expert’s prediction and his or her self-confidence, fame, and (beyond a certain minimum level) depth of knowledge.

Replicability: Widely considered the foundation of modern research; for the scientific community to be convinced that a particular theory or empirical result is real and true, different scientists in different places must independently confirm them and publish their results in a rigorous, refereed journal.

Scientific Truth: Due to the often-intense pressures on scientists to publish something exciting and the speed and power of modern IT, the life span of many scientific “truths” has become almost comically short.

________________________________________________________

Geology

The Hawaiian Islands consist of a long chain of mostly extinct volcanoes that stretches about 2500km from the island of Hawai‘i to Kure Atoll. Beyond Kure, the chain continues in a NW direction for perhaps another 4000km as a series of submerged volcanoes, or seamounts.

Each island was created by a stationary “hot spot” that pushes magma up through the Pacific Plate. This tectonic plate drifts in a NW direction at an annual rate of about 3.5”.

Lō‘ihi: The actively erupting seamount ~30km off Hawai‘i’s southeast coast; it is predicted to emerge as the newest Hawaiian island within the next 200K years.

Pele: The Hawaiian goddess (who lived in modern Volcanoes NP) whose eruptions were believed to be an expression of her longing for her lost true lover.

________________________________________________________

Misc Quotes

“Certainty is for those who have learned and believed only one truth.”

“A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die.”-Max Planck, German Physcist.

As more time passed, I found myself becoming less sure about exactly what we could and should be doing to save Hawai‘i.

The price of an ecological education is living alone in a world of wounds.-Aldo Leopold.

Field biologists who merely collect data and pontificate about it are like garage musicians who never record or publicly perform their music: while they may be highly skilled and dedicated, few outside their immediate circles will ever be able to appreciate and build upon their work. However, because most formal research programs require substantial amounts of public resources, scientists tend to be under much greater pressure than musicians to broadly distribute the fruits of their labors.

One of the cruel ironies is that while the ecology of our planet remains largely unexplored, most of the field data we so laboriously collect and analyze never makes it into print.

You’ve got to be willing to let people criticize something, and that a lot of times you can really improve what you want to do by listening to and addressing their criticism.

Like so many of my colleagues, I was not good at saying no, and I took on far more than I could handle. Trying to juggle all my projects and mushrooming responsibilities while coping with the formidable federal bureaucracy ultimately turned me into one overextended, frazzled, and burnt-out employee. If I kept working at this pace, I was going to turn into another one of those strident, cheerless, cynical conservationists I had vowed never to become.

Restoring Hawai‘i’s tropical forests is no longer financially or physically feasible.-US Forest Service.

“What’s so special about prairies?!”

“I deliberately made the exclosure square so that people wouldn’t mistake it for some kind of natural feature. You can actually spot it now when you’re flying over this part of the island.”

________________________________________________________

Terminology

Epiphyte: A plant that grows on another plant but is not parasitic, including ferns, bromeliads, air plants, and orchids.

Exclosure: An area from which unwanted animals are excluded.

Haole: (In Hawaii) a person who is not a native Hawaiian, especially a white person.

Inventionist Ecology: Deliberately creating new ecosystems and even species.

‘Ka wa ma hope’: The time which comes after or behind; the future (Hawaiian).

‘Ka wa ma ua’: The time in the front or before; the past (Hawaiian).

Mesic: An environment containing a moderate amount of moisture.

Mesophyte: A plant needing only a moderate amount of water.

Miconia calvescens (aka the Green Cancer): Hawai‘i’s poster child of invasive plants; a fast-growing tree from Latin America that produces huge, oval-shaped leaves with striking purple undersides. It has already wreaked ecological and social havoc in about 70% of Tahiti’s native rain forests.

Microsite: A small part of an ecosystem that differs markedly from its immediate surroundings.

Not in my Backyard (NIMBY)

Paradise of the Pacific: Fantasy that most tourists mistakenly think is true of the Hawaiian Islands as a whole.

Pelagic: Of or relating to the open sea.

Plant Extinction Prevention Program (PEP): A program focused on rescuing Hawaiian species with <50 remaining individuals (PEP species).

Scarify: Break up the surface (of soil or pavement).

Special Ecological Areas (SEAs): Intensive management units in which parks employ localized techniques that are not feasible on a parkwide basis.

Southern house mosquito (Culex quinquefasciatus): An alien species in Hawaii and a vector for avian malaria and the virus that causes avian pox. These two diseases have decimated native avifauna and continue to severely limit their distribution and abundance across the Hawaiian archipelago.

________________________________________________________

Chronology

26 Dec, 2004: Extinction of the po’ouli after the last po’ouli dies in captivity.-Restoring Paradise by Cabin.

5-13 Sep, 1992: Hurricane Iniki (CAT 4) strikes Hawaii killing 6 and doing upwards of $3.1B (1992) in damage.

1968: The Population Bomb is published by Paul Ehrlich.-Restoring Paradise by Cabin.

1968: The Tragedy of the Commons is published by Hardin.-Restoring Paradise by Cabin.

1964: The USG passes the US Wilderness Act.-Restoring Paradise by Cabin.

1957: Mauna Loa Observatory begins collecting and analyzing air as part of NOAAs Climate Monitoring and Diagnostics Lab.-Restoring Paradise by Cabin.

1925: ~3K Cactoblastis larvae eggs collected from its native range in Argentina are shipped to Australia. Over the next nine years, >2.7B eggs were mass-reared from this initial shipment and placed on prickly pear infestations in Queensland and New South Wales to biocontrol ~60M acres of prickly pear cactus.-Restoring Paradise by Cabin.

1916: Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park is established, primarily for its accessible volcanic scenery and value for geologic study.-Restoring Paradise by Cabin.

1860s: Rise of the Hawaiian sugar as a dominant economic and political force.-Restoring Paradise by Cabin.

1793-1794: Captain George Vancouver introduces cattle to Hawaii’s King Kamehameha, making him promise to ban the killing of these animals for at least ten years.-Restoring Paradise by Cabin.

Jan, 1778: Captain James Cook accidentally discovers the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii) while searching for a northwest passage between England and the Orient.-Restoring Paradise by Cabin.

16c-17c: European pathogens including smallpox, influenza, tuberculosis, and scarlet fever sweep across the Americas, killing at least three-quarters of the people in the Western Hemisphere. Some scientists now believe that as the tens of millions of indigenous Americans died in the wake of the European conquest of the New World, vast areas of cleared land were left untended. Trees then reclaimed much of that cleared land and pulled billions of tons of carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere through photosynthesis. This massive “natural” reforestation event can account for the sudden drop in atmospheric CO2 recorded in Antarctic ice during the 16c and 17c, which in turn may have diminished the Earth’s heat-trapping capacity and caused the centuries of abnormally cool temperatures in Europe following the Middle Ages (Europe’s so-called Little Ice Age).-Restoring Paradise by Cabin.

1516: Spanish colonists on Hispaniola import African plantains and, inadvertently, their native scale insects.-Restoring Paradise by Cabin.

12 ka: Horses in N. America go extinct following the arriving of humans.-Restoring Paradise by Cabin.

________________________________________________________