SPQR by Beard

Ref: Mary Beard (2016). SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome. Liveright.

_______________________________________________________________

Summary

A history of the Roman Empire from its founding under Romulus in the 8th century BCE to its demise in the 5th Century CE to Visigoths.

_______________________________________________________________

Miscellaneous

SPQR: Senatus Populus Que Romanus, ‘The Senate and People of Rome’.

How far should civil rights be sacrificed in the interests of homeland security?

The ‘people’ was a much larger and amorphous body than the senate, made up, in political terms, of all male Roman citizens; the women had no formal political rights. In 63 BCE there was around a million men spread across the capital and throughout Italy, as well as a few beyond. In practice, the ‘people’ usually comprised the few thousand or the few hundred who, on any particular occasion, chose to turn up to elections, votes or meetings in the city of Rome.

Aborigines: the people who had been there ‘from the beginning’ (ab origine).

‘40,000’ was a common ancient shorthand for ‘a very large number’, like our ‘millions’).

Emetics: A popular regime of detoxification among wealthy Romans involving regular vomiting.

Hymen: Roman deity charged with protecting marriage.

Dignitas: A distinctively Roman combination of clout, prestige and right to respect.

_______________________________________________________________

Life in Ancient Rome

Roman rule was for the most part fairly hands off by the standards of more recent imperial regimes: the locals kept their own calendars, their own coinages, their own gods, their own varied systems of law and civic government.

Employment in Ancient Rome

Most people who needed a regular income to survive (and that was most people) worked, if they could, until they died; the army was an exception in having any kind of retirement package, and even that usually involved working a small farm.

Gambling was rampant in Rome.

Cicero turned his scorn on those who worked for a living: ‘The cash that comes from selling your labour is vulgar and unacceptable for a gentleman … for wages are effectively the bonds of slavery.’ It became a cliché of Roman moralising that a true gentleman was supported by the profits of his estates, not by wage labour, which was inherently dishonourable. Latin vocabulary itself captured the idea: the desired state of humanity was otium (not so much ‘leisure’, as it is usually translated, but the state of being in control of one’s own time); ‘business’ of any kind was its undesirable opposite, negotium (‘not otium’).

Food in Ancient Rome

As with the arrangement of apartment blocks, the Roman pattern is precisely the reverse of our own: the Roman rich, with their kitchens and multiple dining rooms, ate at home; the poor, if they wanted much more than the ancient equivalent of a sandwich, had to eat out.

Slavery in Ancient Rome

But for many Roman slaves, particularly those working in urban domestic contexts rather than toiling in the fields or mines, it was not necessarily a life sentence. They were regularly given their freedom, or they bought it with cash they had managed to save up; and if their owner was a Roman citizen, then they also gained full Roman citizenship, with almost no disadvantages as against those who were freeborn. The scale was so great that some historians reckon that, by the second century CE, the majority of the free citizen population of the city of Rome had slaves somewhere in their ancestry.

Roman Military

‘They create desolation and call it peace’ is a slogan that has often summed up the consequences of military conquest. It was written in the second century CE by the Roman historian Tacitus, referring to Roman power in Britain.

But it was the relationship created between individual generals and their troops that had the most drastic consequences. In essence, the soldiers exchanged absolute loyalty to their commander for the promise of a retirement package – in a trade-off that at best bypassed the interests of the state and at worst turned the legions into a new style of private militia focused entirely on the interests of their general. When the soldiers of Sulla, and later of Julius Caesar, followed their leader and invaded the city of Rome, it was partly because of the relationship between legions and commanders forged by Marius.

Childbirth in Ancient Rome

Caesarian sections, which despite the modern myth had no connection with Julius Caesar, were used simply to cut a live fetus out of a dead or dying woman.

There were some makeshift and dangerous methods of abortion. Prolonged breastfeeding might have delayed further pregnancies for those who did not, as many of the wealthy did, employ wet nurses. And a wide variety of contraceptive potions and devices were recommended, which ranged from completely useless (wearing the worms found in the head of a particular species of hairy spider) to borderline efficacious (inserting almost anything sticky into the vagina). But most of their contraceptive efforts were defeated by the fact that ancient science claimed that the days after a woman ceased menstruating were her most fertile, when the truth is exactly the opposite.

Those babies that were reared were still in danger. The best estimate – based largely on figures from comparable later populations – is that half the children born would have died by the age of ten, from all kinds of sickness and infection, including the common childhood diseases that are no longer fatal. What this means is that, although average life expectancy at birth was probably as low as the mid twenties, a child who survived to the age of ten could expect a lifespan not wildly at variance from our own. According to the same figures, a ten-year-old would on average have another forty years of life left, and a fifty-year-old could reckon on fifteen more.

Simply to maintain the existing population, each woman on average would have needed to bear five or six children. In practice, that rises to something closer to nine when other factors, such as sterility and widowhood, are taken into account. It was hardly a recipe for widespread women’s liberation.

Politics and Transfer of Power in Ancient Rome

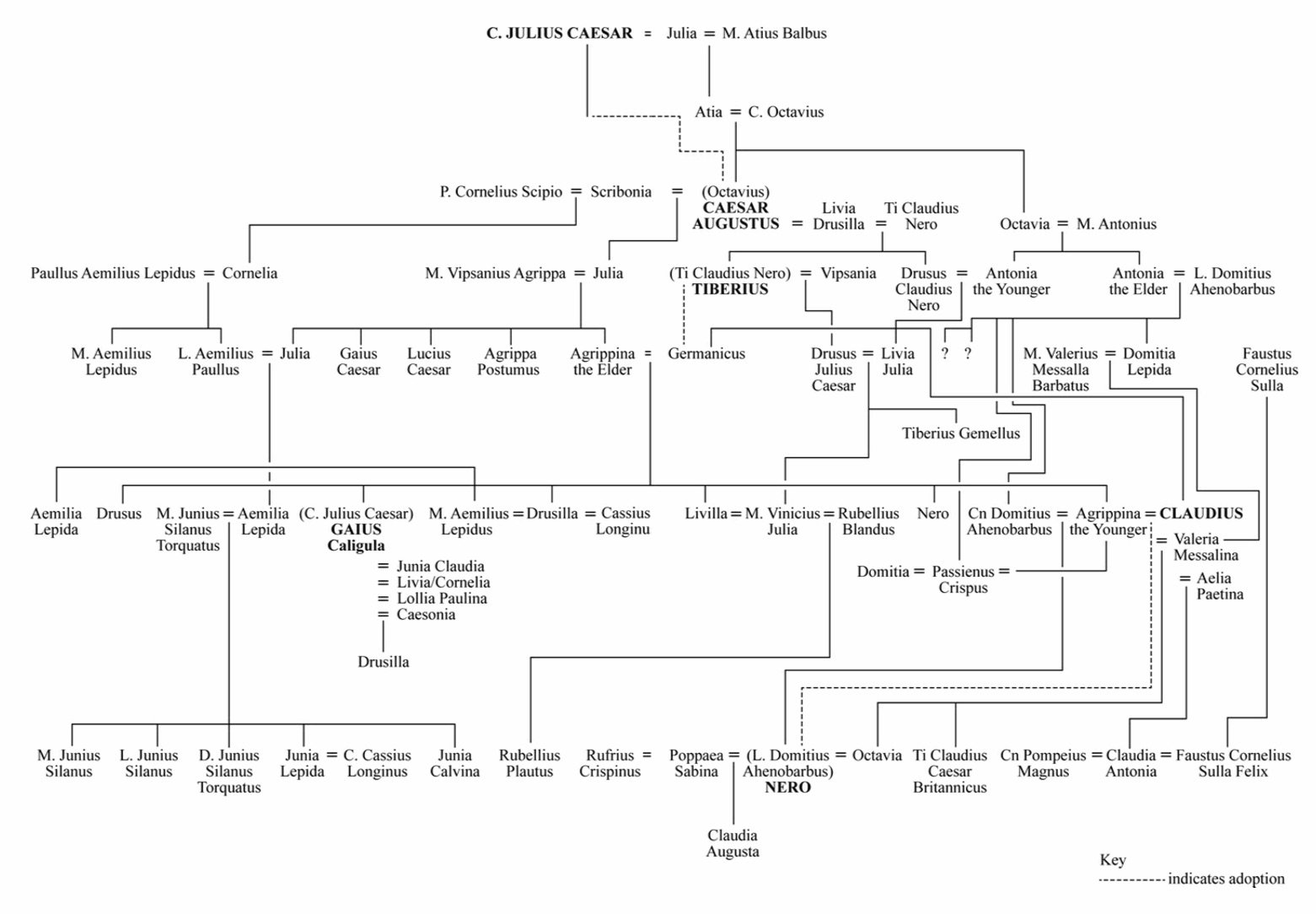

The only reliable way to guarantee a peaceful transition was to have the new emperor on the spot to take over the old Augustus’ signet ring as he breathed his last, with no awkward gap. That is what the rumour-mongers realised: most of the allegations of poisoning under the Julio-Claudians present the murder not as part of a plot to spring some new candidate into power but as an attempt to get the timing right and to ensure a seamless takeover for the man already marked out as the likely successor.

This new system, which operated for most of the second century CE, was sometimes presented as a major shift in the ideology of political power, almost a meritocratic revolution. Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus (now called ‘Pliny the Younger’, to distinguish him from his uncle ‘the Elder’) justified the procedure in precisely those terms, in a speech delivered to the emperor Trajan: ‘When you are about to hand control of the senate and people of Rome, the armies, the provinces, the allies to one man alone, would you look to the belly of a wife to produce him or search for an heir to supreme power only within the walls of your own home? … If he is to rule over all, he must be chosen from all.’

Many of the old uncertainties were resolved, usually in the senate’s favour. Senatorial decrees had previously been advisory only and in the last resort could be ignored or flouted, which was exactly what Caesar and Pompey did in 50 BCE when the senate instructed them both to disarm. These decrees were now given the force of law and gradually, along with the pronouncements of the emperor, became the main form of Roman legislation.

As soon as ambitious individuals came to rely on the nod of the emperor rather than on the popular vote for public office and other sorts of preferment, they no longer had to attract the support of the people en masse, they were no longer compelled to build up a popular following and they had no institutional framework within which to do so.

There was never a written Roman constitution, but Polybius saw in Rome a perfect example in practice of an old Greek philosophical ideal: the ‘mixed constitution’, which combined the best aspects of monarchy, aristocracy and democracy.

The consuls – who had full military command, could summon assemblies of the people and could give orders to all other officials (except the plebeian tribunes) – represented the monarchical element. The senate, which by this date had charge of Rome’s finances, responsibility for delegations to and from other cities and de facto oversight of law and security throughout Roman and allied territory, represented the aristocratic element. The people represented the democratic element.

As in classical Athens, they – and they alone – elected the state officials, passed or rejected laws, made the final decision on going to war and acted as a judicial court for major offences.

The secret, Polybius suggested, lay in a delicate relationship of checks and balances between consuls, the senate and the people, so that neither monarchy nor aristocracy nor democracy ever entirely prevailed.

‘Democracy’ (demokratia) was rooted politically and linguistically in the Greek world. It was never a rallying cry at Rome, even in its limited ancient sense or even for the most radical of Roman popular politicians. In most of the conservative writing that survives, the word means something close to ‘mob rule’.

There is little point in asking how ‘democratic’ the politics of Republican Rome were: Romans fought for, and about, liberty, not democracy.

One of the distinctive features of the Republican political scene were the semi-formal meetings (or contiones), often held immediately before the voting assemblies, in which rival officials tried to win over the people to their point of view

Romans’ forms of political control were equally varied, ranging from hands-off treaties of ‘friendship’, through the taking of hostages as a guarantee of good behaviour, to the more or less permanent presence of Roman troops and Roman officials.

The demands of defending, policing and sometimes extending the empire encouraged, or compelled, the Romans to hand over enormous financial and military resources to individual commanders for years on end.

The Rise of Christianity

Pliny investigated and persecuted Christians continually allowing those under investigation to recant, so long as they proved their sincerity by pouring wine and incense in front of statues of the emperor and the true gods. But in order to find out what was at the bottom of all this, he had two Christian slave women tortured and questioned (in both ancient Greece and Rome, slaves were allowed to give legal evidence only under torture) and concluded that Christianity was ‘nothing other than a perverse and unruly superstition’.

_______________________________________________________________

Chronology

410: The Sack of Rome by the Visigoths led by Alaric.-SPQR by Beard.

337: Emperor Constantine converts to Christianity on his deathbed.-SPQR by Beard.

212: Roman Emperor Caracalla makes every single free inhabitant of the Roman Empire a full Roman Citizen.-SPQR by Beard.

193: Roman Civil War.

192: Emperor Commodus, son of Marcus Aurelius, is assassinated, which is followed by the intervention of the praetorians and of rival legions from outside Rome and by another civil war, which marked the beginning of the end of the Augustan template of imperial rule.-SPQR by Beard.

144: Publius Aelius Aristides writes several volumes on his illness, hypochondria.-SPQR by Beard.

120s: Completion of Hadrian’s Pantheon, ‘temple of all gods,’ the concrete span of its dome remained the widest in the world until 1958.-SPQR by Beard

117: Hadrian becomes emperor of Rome, abandoning most Mesopotamia.-SPQR by Beard.

114-117: Roman emperor Trajan invades and conquers much of Mesopotamia in moder day Iran- the furthest East that Roman power was every formally extended.-SPQR by Beard.

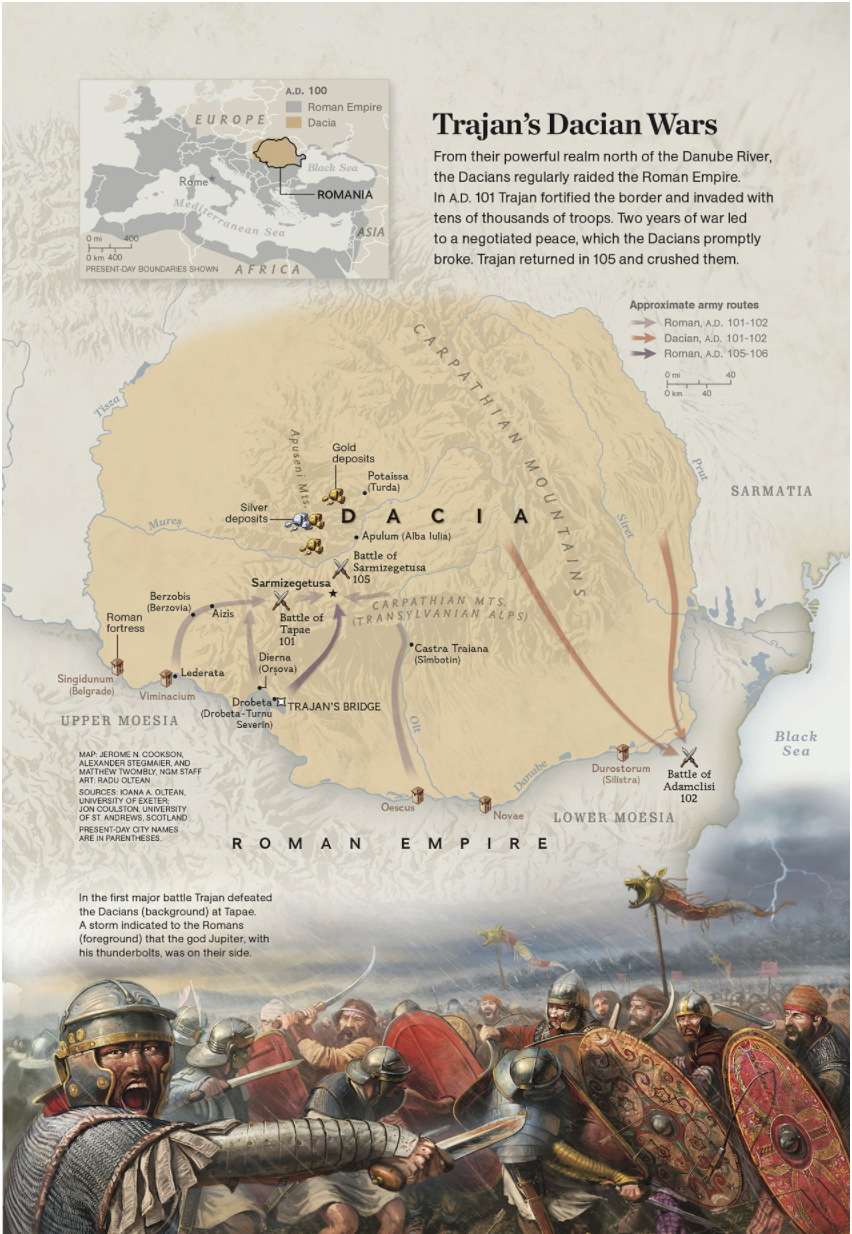

101-102: Roman emperor Trajan conquers Dacia, part of what is now Romania.-SPQR by Beard.

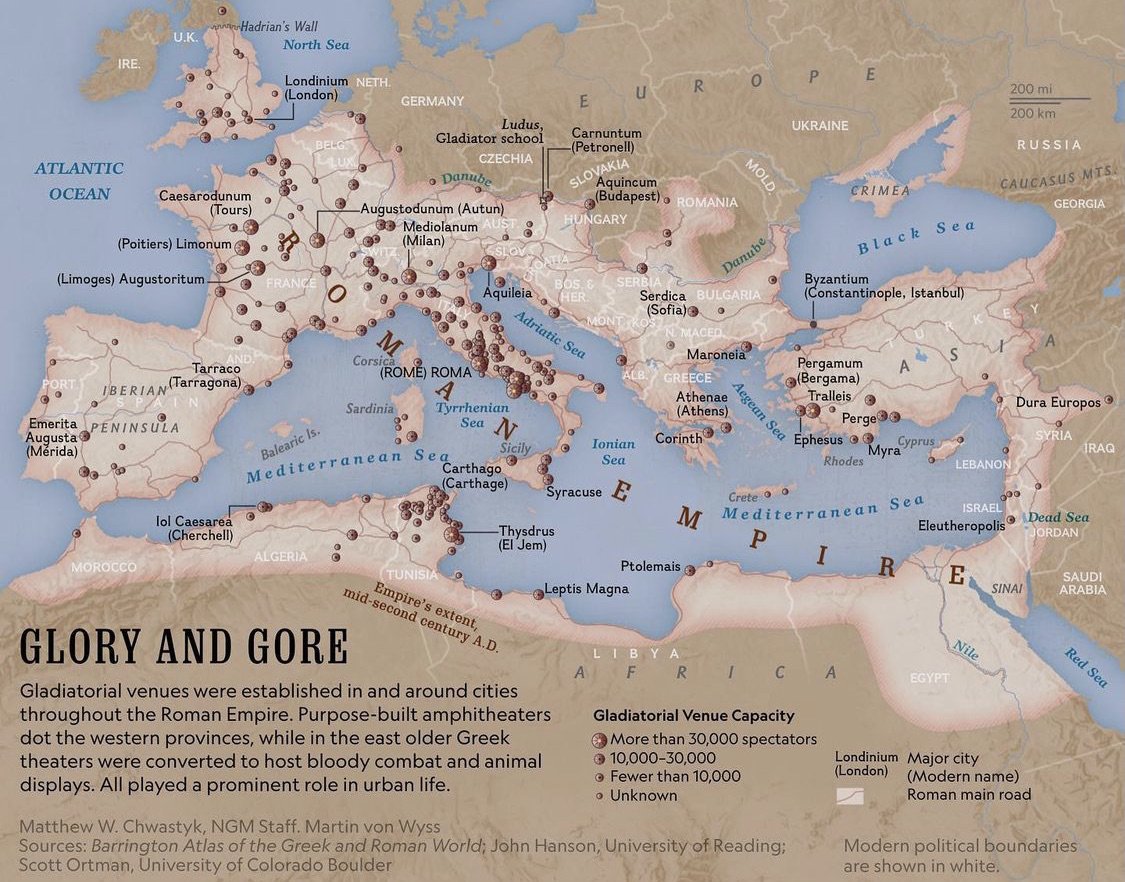

80: Vespasian’s most famous construction, the amphitheatre is inaugurated under his son. Eventually known as the Colosseum, from a colossal statue of Nero that stood close by and lasted long after Nero’s end, this was simultaneously a massive building project (it took almost ten years to finish, using 100,000 cubic metres of stone), a commemoration of his victory over Jewish rebels (the booty from the war paid for it) and a conspicuous act of generosity to the Roman people (the most famous popular entertainment venue ever). It was also a criticism of his predecessor, pointedly built on the site that had once belonged to Nero’s private park.-SPQR by Beard.

68-69: Roman Civil War.

24, Jan 41: Assassination of Emperor Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus by three soldiers from the Prateorian Guard.-SPQR by Beard.

As soon as news of the murder leaked out, the Germans proved their brutal, thuggish loyalty. They ran through the Palatine, killing anyone they suspected of involvement in the plot. One senator was slaughtered.

The Praetorian Guard, who had a low view of the capabilities of the senate and no desire to return to the Republic, had already picked a new emperor. The story was that, terrified by the violence and commotion, Gaius’ uncle the fifty-year-old Claudius had hidden himself down another dark alley. But he was quickly discovered by the praetorians and, though fearing he too was about to be killed, was hailed as emperor instead.-SPQR by Beard.

37: Death of Roman Emperor Tiberius who is succeeded by his great-nephew, Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus.-SPQR by Beard.

19 Aug, 14: Emperor Tiberius takes over from his adoptive farther, Augustus, who dies in his bed.-SPQR by Beard.

9: The Battle of Teutoburg Forest just North of the town of Osnarbrück, in which Roman Commander Publius Quinctilius loses three legions to German rebel Arminius ‘Herman the German,’ thus ending the Augustan expansion of the empire.-SPQR by Beard.

On his death, Augustus left instructions that the empire should not be extended any further.

2: Ovid releases his Love Lessons, ‘Ars Armatoria,’ a spoof on how to pick up a partner.

8 BCE: The Roman senate renames the month Sextilis as August.

27 BCE: Octavian becomes Augustus (a made-up title meaning something close to ‘Revered One’).

30 BCE: Octavian becomes Emperor of Rome.

Most of his formal powers were officially voted to him by the senate and cast almost entirely in a traditional Republican format, his continued use of the title ‘son of a god’ being the only important exception. And he lived in no grand palace but in the sort of house on the Palatine Hill where you would expect to find a senator, and where his wife Livia could occasionally be spotted working her wool. The word that Romans most often used to describe his position was princeps, meaning ‘first citizen’ rather than ‘emperor’, as we choose to call him, and one of his most famous watchwords was civilitas – ‘we’re all citizens together’.-SPQR by Beard.

For obvious Roman reasons, he did not call himself king. He made an elaborate show of rejecting the title ‘dictator’ too, distancing himself from Caesar’s example.-SPQR by Beard.

Augustus’ power, as he formulates it, is signaled by military conquest, by his role of protector and benefactor of the people in Rome and by construction and reconstruction on a vast scale; and it was underpinned by massive reserves of cash, combined with the display of respect for the ancient traditions of Rome. It was against this blueprint that every emperor for the next 200 years was judged.-SPQR by Beard.

Augustus became something no Roman had been before: the commander-in-chief of all the armed forces, who appointed their major officers, decided where and against whom the soldiers should fight, and claimed all victories as by definition his own, whoever had commanded on the ground. He also secured his position by severing the links of dependence and personal loyalty between armies and their individual commanders, largely thanks to a simple, practical process of pension reform. This must count among the most significant innovations of his whole rule. He established uniform terms and conditions of army employment, fixing a standard term of service of sixteen years (soon raised to twenty) for legionaries and guaranteeing them on retirement a cash settlement at public expense amounting to about twelve times their annual pay or an equivalent in land.-SPQR by Beard.

In other words, after hundreds of years of a semi-public, semi-private militia, Augustus fully nationalized the Roman legions and removed them from politics.-SPQR by Beard

30 BCE: Octavian sails to Alexandria to finish the job. In what has often been written up as a kind of tragic farce, Antony stabbed himself when he thought that Cleopatra was already dead, though he lived just long enough to discover that she was not. A week or so later she too is said to have killed herself, with the bite from a snake smuggled into her quarters in a basket of fruit. According to the official version, her motive was to deprive Octavian of her presence in his triumphal procession: ‘I will not be triumphed over,’-SPQR by Beard

Octavian took no chances with Caesarion, given his supposed paternity. Now aged sixteen, he was killed.

Sep, 31 BCE: The Battle of Actium (‘promontory’) in Northern Greece; Naval forces under Octavian defeat Antony and Cleopatra forces at sea.

Octavian’s easy victory was owed to his second in command, Marcus Agrippa, who managed to cut off their opponents’ supplies; to a handful of well-informed deserters who disclosed the enemy plans; and to Antony and Cleopatra themselves, who simply disappeared.-SPQR by Beard

32 BCE: Antony divorces Octavia (Octavians sister) and Octavian responds by getting his hands on Antony’s will and reading out particularly incriminating selections from it to the senate. These revealed that Antony recognized young Caesarion (Cleopatra’s son) as Julius Caesar’s son, that he was planning to leave large amounts of money to the children he had had with Cleopatra and that he wanted to be buried in Alexandria by Cleopatra’s side, even if he died in Rome. The rumour on the Roman streets was that his long-term plans were to abandon the city of Romulus and transfer the capital wholesale to Egypt. It was against this background that open war broke out.-SPQR by Beard

36 BCE: Lepidus is squeezed out of the second triumvirate leaving only Octavian and Antony.-SPQR by Beard

40 BCE: Octavian and Antony effectively carve up the Mediterranean world between themselves, leaving just a small patch for Lepidus.-SPQR by Beard

Oct, 42 BCE: The united forces of the triumvirate defeated Brutus and Cassius near the town of Philippi in the far north of Greece (the focus of much of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar). The victorious allies then began even more systematically to turn on one another. In fact, when Octavian returned from Philippi to Italy to oversee a massive programme of land confiscation, aimed at providing settlement packages for thousands of dangerously dissatisfied retiring soldiers, he soon found himself facing the armed opposition of Fulvia and Mark Antony’s brother Lucius Antonius. They had taken up the cause of the landowners who had been dispossessed, and even managed to gain control of the city of Rome, albeit briefly. Octavian soon had them under siege in the town of Perusia (modern Perugia). Starvation forced their surrender early in 40 BCE, but the stage had been set for more than a decade of further war, interspersed with brief truces, between the different parties who claimed to represent Caesar’s legacy.-SPQR by Beard.

As a pledge for the future, the widowed Antony married Octavian’s sister, Octavia. It was, however, an empty pledge, as by this date Antony was already in the partnership that would come to define him; he was more or less living with Queen Cleopatra of Egypt, and she had just given birth to his twins.-SPQR by Beard.

Jan, 42 BCE: A compliant senate formally declares Caesar a God. Octavian was soon trumpeting his new title and status: ‘son of a god’. More than a decade of civil war followed.-SPQR by Beard.

Winter, 43 BCE: In little more than eighteen months after Octavian’s arrival in Italy, the politics of Rome had been turned upside down. Brutus and Cassius had been allocated provinces in the East and left Italy. Octavian and Antony had come to blows in a series of military engagements in northern Italy and then patched things up again by forming with Lepidus a ‘triumvirate for establishing government’. This was a formal, five-year agreement that gave each of the three men (triumviri) power equal to consuls, their pick of what provinces they wanted and control over elections. Rome was in the control of a junta.-SPQR by Beard.

Apr, 44 BCE: Octavian, Caesar’s appointed heir, arrives in Rome, where from the other side of the Adriatic he had been involved in the preparations for an invasion of Parthia. Whatever the rumours and allegations, and whatever the status of the little boy whom Cleopatra had pointedly named Caesarion, Caesar had recognized no legitimate children. So he had taken the unusual step of adopting his great-nephew in his will, making him his son and the main beneficiary of his fortune. Gaius Octavius was then only eighteen years old and soon started capitalising on the famous name that came with his adoption by calling himself Gaius Julius Caesar – though to his enemies, as to most modern writers wanting to avoid confusion, he was known as Octavianus, or Octavian (that is, the ‘ex-Octavius’).-SPQR by Beard.

Octavian chose to frame all his powers in terms of regular Republican office holding. To begin with, that meant being repeatedly elected consul, eleven times in all between 43 and 23 BCE, and on two isolated occasions later. Then, from the mid 20s BCE, he arranged to be granted a series of formal powers that were modelled on those of traditional Roman political offices but not the offices themselves: he took ‘the power of a tribune’ but did not hold the tribunate, and ‘the rights of a consul’ without holding the consulship.-SPQR by Beard.

15 Mar, 44 BCE: Julius Caesar is assassinated on the Ides of March.-SPQR by Beard.

A gang of twenty or so senators crowded round Caesar on the pretext of handing him a petition. One backbencher gave the cue for the attack by kneeling at the dictator’s feet and pulling on his toga. The assassins were not very accurate in their aim, or perhaps they were terrified into clumsiness. One of the first strikes with the dagger missed entirely and gave Caesar the chance to fight back with the only weapon he had to hand – his sharp pen. According to the earliest account to survive, by Nicolaus of Damascus, a Greek historian from Syria writing fifty years later but likely drawing on eyewitness descriptions, several assassins were caught in ‘friendly fire’: Gaius Cassius Longinus lunged at Caesar but ended up gashing Brutus; another blow missed its target and landed in a comrade’s thigh.-SPQR by Beard.

At the time of his death, Pompey’s son Sextus still had a force of at least six legions in Spain and was continuing to fight for his father’s cause. But Caesar was mustering a vast force of almost 100,000 soldiers for an attack on the Parthian Empire, a revenge for the ignominious defeat of Crassus at Carrhae and a useful opportunity for military glory against a foreign rather than a Roman enemy. It was just a few days before he was due to leave for the East, on 18 March, that a group of twenty or so disgruntled senators, supported actively or passively by a few dozen more, killed him.-SPQR by Beard.

49-44 BCE: Roman Civil War and the dictatorship of Julius Caesar.-SPQR by Beard.

44 BCE: The Roman Senate makes Caesar dictator for life.-SPQR by Beard.

46 BCE: The Roman Senate makes Caesar dictator for ten years.-SPQR by Beard.

47 BCE: The Battle of Zela; Julius Caesar defeats Mithridates’ son Pharnaces, who had died in battle near the Black Sea, was commemorated in the same celebrations by a single placard on which was written one of the world’s most famous slogans ever: ‘Veni, vidi, vici’ (‘I came, I saw, I conquered’, intended to capture the speed of Caesar’s success).-SPQR by Beard.

48-45 BCE: Caesar overcomes his Roman adversaries in Africa and Spain as well as squashing trouble from Pharnaces, the son and usurper of Mithridates.-SPQR by Beard.

48 BCE: Caesars forces defeat Pompey’s forces at the Battle of Pharsalus in N. Greece (Pompey is murdered soon after when he attempts to take refuge in Egypt), the Roman senate vote again to make Caesar dictator for a year. Pompey was expecting a warm welcome as he put to shore. In fact, he was decapitated by the henchmen of a local dynast, who calculated that disposing of the enemy leader would ingratiate him with Caesar. The murder, however, proved a wrong move for its perpetrators. Caesar, who turned up a few days later, apparently wept as he was presented with Pompey’s pickled head and shortly backed one of the rivals to the throne of Egypt. That rival was Queen Cleopatra VII, best known for her alliance, political and romantic, with Mark Antony in the next round of Roman civil wars. But at this point her interests lay with Caesar, with whom she had an open affair and – if her claims about paternity are to be believed – a child.-SPQR by Beard.

49 BCE: Caesar is first appointed to the office for a short term, to conduct elections to the consulship for the next year, an entirely traditional procedure, except for the entirely untraditional fact that he oversaw the election of himself.-SPQR by Beard.

Despite his rare appearances in Rome, Caesar initiated a vast programme of reforms going beyond even the scale of Sulla’s. One of them governs life even now. For – with some help from the specialist scientists he met in Alexandria – Caesar introduced into Rome what has become the modern Western system of timekeeping. The traditional Roman year was only 355 days long, and it had for centuries been the job of Roman priests to add in an extra month from time to time to keep the civic calendar in step with the natural seasons. Using Alexandrian know-how, Caesar corrected the error and, for the future, established a year with 365 days, with an extra day inserted at the end of February every four years.-SPQR by Beard.

The majority of Romans still preferred the reforms of Caesar – the support for the poor, the overseas settlements and the occasional cash handouts – to fine-sounding ideas of liberty, which might amount to not much more than an alibi for elite self-interest and the continued exploitation of the underclass.-SPQR by Beard.

The distribution of cheap grain was Gaius’ most influential reform.-SPQR by Beard.

Whichever side won, as Cicero again observed, the result was set to be much the same: slavery for Rome. What came to be seen as a war between liberty and one-man rule was really a war to choose between rival emperors.-SPQR by Beard.

10 Jan, 49 BCE: Julius Caesar, with just one of his legions from Gaul, crossed the Rubicon, the river that marked the northern boundary of Italy.-SPQR by Beard.

For us, ‘to cross the Rubicon’ has come to mean ‘to pass the point of no return’.-SPQR by Beard.

The underlying issue was brutally straightforward. Would Caesar, with more than 40,000 troops at his disposal only a few days from Italy, follow the example of Sulla or of Pompey?-SPQR by Beard.

Caesar and Pompey, the one-time allies, were now the rival commanders, spread throughout the Mediterranean world. Rome’s internal conflicts were no longer restricted to Italy. The decisive battle was fought in central Greece, and Pompey ended up murdered on the coast of Egypt, beheaded by some Egyptian double-dealers he had imagined were his allies.-SPQR by Beard.

Dec, 50 BCE: The Roman senate votes by a majority of 370 to 22 that Caesar and Pompey should simultaneously give up their commands. in response to this overwhelming vote, Pompey took no notice and Caesar, after a few more rounds of fruitless negotiation, marched into Italy.-SPQR by Beard.

52 BCE: Roman Consul Clodius is murder leaving Pompey as the sole Roman Consul. Rather than resort to appointing a dictator to take charge of the growing crisis, with all the memories of Sulla’s dictatorship, the senate decided to give to one man an office which by definition had always been shared between two. This time the gamble paid off. Within a few months Pompey had not only taken firm control of the city but also taken a colleague, albeit keeping it in the family: it was his new father-in-law.-SPQR by Beard.

54 BCE: Pompey’s wife Julia (Caesars daughter) dies in childbirth, leading to the political breakdown between Pompey and Caesar. Pompey had initially sealed his agreement with Caesar in the Gang of Three by marrying Caesar’s daughter, Julia.-SPQR by Beard.

55-53 BCE: The Battle of Carrhae on the border of Turkey and Syria; the Parthians (modern Iran) defeat a Roman conquest led by Marcus Crassus, who is decapitated and his Army’s ceremonial standards captured.-SPQR by Beard.

58-50 BCE: The ‘Celtic Holocaust;’ Roman Legions under Julius Caesar conquer and murder untold numbers of Celts in Gaul extending their power as far North as the isle of Britain. In doing this, Caesar laid the foundations for the political geography of modern Europe, as well as slaughtering up to a million people over the whole region. . Caesar’s description of these campaigns in the seven volumes of his Commentaries on the Gallic War, an edited version of his official annual dispatches from the front line sent back to Rome, starts with its famous, clinical opener, ‘Gallia est omnis divisa in partes tres’ (‘The whole of Gaul is divided into three parts’). It ranks alongside Xenophon’s description (the Anabasis, or Going Up) of his exploits with a Greek mercenary army, written in the fourth century BCE, as the only detailed eyewitness account of any ancient warfare to survive.-SPQR by Beard.

58 BCE: The Roman people vote, in general terms, to expel anyone who had put a citizen to death without trial; forcing Cicero to leave Rome, just before another bill was passed specifically singling him out, by name, for exile.-SPQR by Beard.

59 BCE: Caesar is elected consul and secures a military command for himself in southern Gaul, to which a vast area on the other side of the Alps was soon added.-SPQR by Beard.

60-50 BCE: The Roman Gang of Three. Against a background of street violence and a breakdown in political order, three men– Pompey, Julius Caesar and Marcus Licinius Crassus – made an informal deal to use their combined influence, connections and money to fix the political process in their own interests. This ‘Gang of Three’, or ‘Three-Headed Monster’, as one contemporary satirist put it, for the first time effectively took public decisions into private hands. Through a series of behind-the-scenes arrangements, bribes and threats, they ensured that consulships and military commands went where they chose and that key decisions went their way.-SPQR by Beard.

63 BCE: Rome is a vast metropolis with more than a million inhabitants.-SPQR by Beard.

66-61 BCE: Pompey is granted command over the defeat of Mithradates; powers were to include almost complete control over a large swathe of the eastern Mediterranean for an unlimited period, with more than 40,000 troops at his disposal, and the right to make peace or war and to arrange treaties more or less independently.-SPQR by Beard.

Mithradates was a real threat to Rome’s security and that Pompey was the only man for the job. From the heartland of his kingdom on the Black Sea the king had certainly scored occasional terrifying victories over Roman interests across the eastern Mediterranean, including in 88 BCE a notorious, and highly mythologised, massacre of tens of thousands of Romans and Italians on a single day.-SPQR by Beard.

Mithradates was quickly driven out of Asia Minor, to his territories in the Crimea, where he was later ousted in a coup by one of his sons and killed himself.-SPQR by Beard.

73-71 BCE: The Spartacus Slave Rebellion; under the leadership of Spartacus, fifty or so slave gladiators, improvising weapons out of kitchen equipment, escaped from a gladiatorial training school at Capua in southern Italy and went on the run. They spent the next two years gathering support and withstanding several Roman armies until they were eventually crushed in 71 BCE, the survivors crucified in a grisly parade along the Appian Way.-SPQR by Beard.

83-82 BCE: Sulla re-establishes the city of Rome and engineers his own election as ‘dictator for making laws and restoring order to the res publica’. The dictatorship was an old emergency office which gave sole power to an individual on a temporary basis to cope with a crisis. Sullah took away the tribunes’ right to introduce legislation, curtailed their veto and made anyone who had held the tribunate ineligible for any future elected office – a guaranteed way of turning it into a dead end. The removal of these restrictions became the main rallying cry of the opposition to Sulla, and within ten years of his retirement all were repealed, paving the way for another generation of powerful and prominent tribunes.-SPQR by Beard.

85 BCE: Defeat of King Mithradates; The Roman Army led by Sullah defeats Mithradates.-SPQR by Beard.

91-89 BCE: The Social War (a coalition of Italian allies, or socii) begins after the massacre of Romans at Asculum; Rome defeats the Italians in a multi-year War after a Roman envoy insulted the people of Asculum in central Italy. They responded by killing him and all the other Romans in the town. This brutal piece of ethnic cleansing set the tone for what followed, which was not far short of civil war: ‘It can be called a war against socii, to lessen the odium of it; the truth is it was a civil war, against citizens,’ as one Roman historian later summed it up. And it involved fighting throughout much of the peninsula. The Romans invested enormous forces to defeat the Italians and won victory at the cost of heavy losses and considerable panic. Most of the conflict was over relatively quickly, within a couple of years. Peace was apparently hastened by one simple expedient: the Romans offered full citizenship to those Italians who had not taken up arms against Rome or were prepared to lay them down.-SPQR by Beard.

89 BCE: The Siege of Pompeii ends the Social War.

90-89 BCE: Rome extends full citizenship to most of the Italian peninsula. Italy was now the closest thing to a nation state that the classical world ever knew.-SPQR by Beard.

120s BCE: The makings for the Social War begins; a Roman consul was travelling through Italy with his wife and came to the small town of Teanum (modern Teano, about 100 miles south of Rome). The lady decided she wanted to use the baths there usually reserved for men, so the mayor had them prepared for her and the regular bathers thrown out. But she complained that the facilities were neither ready in time nor clean enough. ‘So a stake was set up in the forum, and Teanum’s mayor, the most distinguished man in the town, was taken and tied to it. His clothes were stripped off and he was beaten with sticks.’ It ended with many of the allies going to war on Rome in the Social War, one of the deadliest and most puzzling conflicts in Roman history.-SPQR by Beard.

125 BCE: The people of Fregellae attempted to break away from Rome but were crushed by a Roman army under the same Lucius Opimius who a few years later eliminated Gaius Gracchus.-SPQR by Beard

133 BCE: Lynching of Roman Politician Tiberius Gracchus.

133 BCE: Tiberius is elected a tribune to the people. He saw the problem in terms of the displacement of the poor from farming land. So did the poor themselves, if the story of their graffiti campaign in Rome urging him to restore ‘land to the poor’ is true.-SPQR by Beard.

Nevertheless, it was the events of 133 BCE that crystallised the opposition between those who championed the rights, liberty and benefits of the people and those who, to put it in their own terms, thought it prudent for the state to be guided by the experience and wisdom of the ‘best men’ (optimi), who in practice were more or less synonymous with the rich. Cicero uses the word partes for these two groups (populares and optimates, as they were sometimes called), but they were not parties in the modern sense: they had no members, official leaders or agreed manifestos.-SPQR by Beard

Cicero, looking back from the middle of the next century, could present 133 BCE as a decisive year precisely because it opened up a major fault line in Roman politics and society that was not closed again during his lifetime: ‘The death of Tiberius Gracchus,’ he wrote, ‘and even before that the whole rationale behind his tribunate, divided a united people into two distinct groups [partes].’-SPQR by Beard.

133 BCE: Detah of King Attalus III of Pergamum who makes ‘the Roman people’ the heir to his property and large kingdom in what is now Turkey.-SPQR by Beard.

139 BCE: A radical tribune introduced a law to ensure that Roman elections were conducted by secret ballot; unheard of at this point in history.-SPQR by Beard.

146 BCE: Roman armies led by Aemilianus invade N. Africa and destroy Carthage ending the Third Punic War. They reduced the ancient city of Carthage to rubble and sold most of its surviving inhabitants into slavery.

149 BCE: a permanent criminal court is established in Rome, with the main aim of giving foreigners compensation and the right of redress against extortion by their Roman rulers.-SPQR by Beard.

168 BCE: Roman Armies led by Aemilius Paullus and Scipio Aemilianus defeat the Macedonians in Greece led by Perseus after the Greeks considered supporting Hannibal in the Punic Wars, resulting in Roman control over Greece. Macedon is broken up into four independent, self-governing states; that paid tax to Rome, at half the rate that Perseus had levied it; and, in this case, the Macedonian mines were shut down, to prevent their resources from being used to build up a new power base in the region.-SPQR by Beard.

190 BCE: Roman Armies led by Scipio Asiaticus defeats the Syrians and King Antiochus ‘the great’; Not only was he busy modelling himself on Alexander the Great and extending his power base accordingly, but he had also given a home to Hannibal, now in exile from Carthage, who was reputed to be offering the king master classes in how to confront the Romans.-SPQR by Beard.

218-201 BCE: The Second Punic War is fought between Rome and Carthage.

Best remembered for the heroic failure of Hannibal, who crossed the Alps with his elephants (more of a propaganda coup than a practical military asset) and inflicted vast casualties on the Romans in Italy.-SPQR by Beard.

After more than a decade of inconclusive warfare did Hannibal’s home government – increasingly uneasy about the whole escapade and now with the invading army of Africanus to face – recall him to Carthage.-SPQR by Beard.

202 BCE: Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus, a great-grandson of Barbatus, secures the final defeat of Hannibal: he invaded the Carthaginian’s home territory in North Africa and at the Battle of Zama, near Carthage, routed his army, with some help from Hannibal’s elephants, who ran amok and trampled over their own side.-SPQR by Beard.

216 BCE: The Battle of Cannae; the Romans led by General Publius Scipio are defeated by the Carthaginians led by Hannibal with up to 70,000 Roman deaths in a single afternoon, making it as great a bloodbath as Gettysburg or the first day of the Somme, maybe even greater.-SPQR by Beard.

218 BCE: The Carthaginian warlord, Hannibal, crosses the Alps with his thirty-seven elephants and inflicts terrible losses on the Romans before they eventually managed to fight him off.-SPQR by Beard.

264-241 BCE: The First Punic War is fought between Rome and Carthage.

Largely fought in Sicily and on the seas round about, except for one disastrous Roman excursion to the Carthaginian homeland, in North Africa. It ended with Sicily, Sardinia (after a few years), and Corsica (after a few years) under Roman control.-SPQR by Beard.

280 BCE: Pyrrhus, the ruler of a kingdom in N. Greece, sails to Italy to support the town of Tarentum against the Romans. His self-deprecating joke – that his victories against Rome cost him so many men that he could not afford another – lies behind the modern phrase ‘Pyrrhic victory’, meaning one that takes such a heavy toll that it is tantamount to defeat. He was the first to pull off the stunt of bringing elephants to Italy.-SPQR by Beard.

367 BCE: The Conflict of the Orders ends political discrimination against the plebeians while effectively replacing a governing class defined by birth with one defined by wealth and achievement.-SPQR by Beard.

390 BCE: A posse of marauding Gauls occupies the city of Rome.-SPQR by Beard.

500 BCE: The Roman Republic releases the law of the 12 Tables; a commitment to agreed, shared and publicly acknowledged procedures for resolving disputes and some thoughts on dealing with practical and theoretical obstacles to that. There were hierarchies within the free citizen population too. One clause draws a distinction between patricians and plebeians, another between assidui (men of property) and proletarii (those without property – whose contribution to the city was the production of offspring, proles). Another refers to ‘patrons’ and ‘clients’ and to a relationship of dependency and mutual obligation between richer and poorer citizens that remained important throughout Roman history.-SPQR by Beard.

500 BCE: The Roman Republic is founded by Servius Tullius (the Grand Constitution) who conducts a census, reorganizes the Army, and organizes elections.

The army was to be made up of 193 ‘centuries’, distinguished according to the type of equipment the soldiers used; this equipment was related to the census classification, on the principle of ‘the richer you are, the more substantial and expensive equipment you can provide for yourself’. Starting at the top, there were eighty centuries of men from the richest, first class, who fought in a full kit of heavy bronze armour; below these came four more classes, wearing progressively lighter armour down to the fifth class, of thirty centuries, who fought with just slings and stones. In addition, above these there were an extra eighteen centuries of elite cavalry, plus some special groups of engineers and musicians, and at the very bottom of the pecking order a single century of the very poorest, who were entirely exempt from military service.-SPQR by Beard.

Servius Tullius is supposed to have used these same structures as the basis of one main voting assembly of the Roman people: the Centuriate Assembly (so called after the centuries), which in Cicero’s day came together to elect senior officials, including the consuls, and to vote on laws and on decisions to go to war. Each century had just one block vote; and the consequence (or intention) was to hand to the centuries of the rich an overwhelming, built-in political advantage. If they stuck together, the eighty centuries of the richest, first class plus the eighteen centuries of elite cavalry could outvote all the other classes put together. To put it another way, the individual rich voter had far greater voting power than his poorer fellow citizens. This was because, despite their name – which looks as if it should mean that they comprised 100 (centum) men each – the centuries were in fact very different in size. The richest citizens were far fewer in number than the poor, but they were divided among eighty centuries, as against the twenty or thirty for the more populous lower classes, or the single century for the mass of the very poorest. Power was vested in the wealthy, both communally and individually.-SPQR by Beard.

500 BCE: The Rape of Lucretia and the Expulsion of the Roman Kings (End of the Roman Monarchy).

It starts with a group of young Romans who were trying to find ways of passing the time while besieging the nearby town of Ardea. One evening, they were having a drunken competition about whose wife was best, when one of their number, Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus, suggested that they should simply ride back home (it was only a few miles away) and inspect the women; this would prove, he claimed, the superiority of his own Lucretia. Indeed it did: for while all the other wives were discovered partying in the absence of their menfolk, Lucretia was doing exactly what was expected of a virtuous Roman woman – working at her loom, among her maids. She then dutifully offered supper to her husband and his guests. For during that visit, we are told, Sextus Tarquinius conceived a fatal passion for Lucretia, and one evening shortly afterwards he rode back to her house. After being politely entertained again, he came to her room and demanded sex with her, at knifepoint. When the simple threat of death did not move her, Tarquinius exploited instead her fear of dishonour: he threatened to kill both her and a slave (visible in Titian’s painting [see plate 4]) so that it would look as if she had been caught in the most disgraceful form of adultery. Faced with this, Lucretia acceded, but when Tarquinius had returned to Ardea, she sent for her husband and father, told them what had happened – and killed herself. At the same time, this was seen as a fundamentally political moment, for in the story it leads directly to the expulsion of the kings and the start of the free Republic. As soon as Lucretia stabbed herself, Lucius Junius Brutus – who had accompanied her husband to the scene – took the dagger from her body and, while her family was too distressed to speak, vowed to rid Rome of kings forever. After ensuring the support of the army and the people, who were appalled by the rape and fed up with labouring on the drain, Lucius Junius Brutus forced Tarquin and his sons into exile.-SPQR by Beard.

Fall of the Second Tarquin King- Tarquinius Superbus (taquin the proud).-SPQR by Beard.

650 BCE: The Law of Draco is established in Greece (now a byword for harshness- draconian).-SPQR by Beard.

750 BCE: Romulus declared Rome an ‘asylum’ and encouraged the rabble and dispossessed of the rest of Italy to join him: runaway slaves, convicted criminals, exiles and refugees. This produced plenty of men. But in order to get women, so Livy’s story goes, Romulus had to resort to a ruse – and to rape. He invited the neighbouring peoples, the Sabines and the Latins, from the area around Rome known as Latium, to come and enjoy a religious festival plus entertainments, families and all. In the middle of the proceedings, he gave a signal for his men to abduct the young women among the visitors and to carry them off as their wives. They went to war with the Romans for the return of their daughters. The Romans easily defeated the Latins but not the Sabines, and the conflict dragged on. During battle, the captured women bravely entered the field and begged their husbands on one side and fathers on the other to stop the fighting. ‘We’ll better die ourselves,’ they explained, ‘than live without either of you, as widows or as orphans.’ Their intervention worked. Not only was peace brought about, but Rome was said to have become a joint Roman–Sabine town, a single community, under the shared rule of Romulus and the Sabine king Titus Tatius.-SPQR by Beard.

Romulus preys to the god Jupiter, in fact to Jupiter Stator, ‘Jupiter who holds men firm’. He would build a temple in thanks, Romulus promised the god, if only the Romans would resist the temptation to run for it, and stand their ground against the enemy. They did, and the Temple of Jupiter Stator was erected on that very spot, the first in a long series of shrines and temples in the city built to commemorate divine help in securing military victory or Rome.-SPQR by Beard.

The idea of the asylum reflected Roman political culture’s extraordinary openness and willingness to incorporate outsiders, which set it apart from every other ancient Western society that we know. No ancient Greek city was remotely as incorporating as this; Athens in particular rigidly restricted access to citizenship.- SPQR by Beard.

753- 500 BCE: The Age of the Roman Kings.-SPQR by Beard.

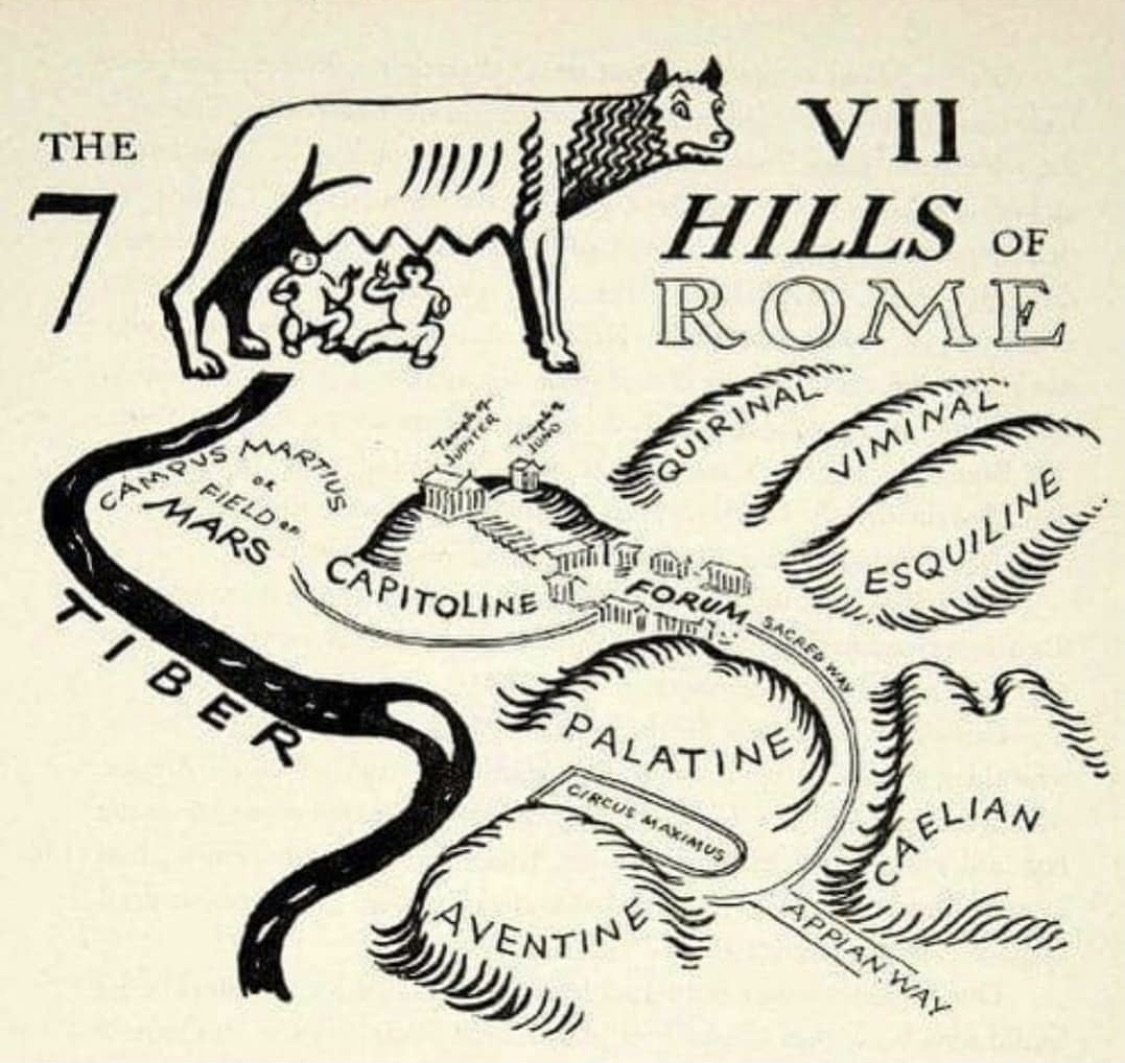

753 BCE: Twins, Romulus and Remus found the City of Rome. Romulus elects to site the city on the Palatine (Palace) Hill while his brother Remus opts for the Aventine, insultingly jumping over the defences that Romulus was constructing. There were various versions of what happened next. But the commonest (according to Livy) was that Romulus responded by killing his brother and so became the sole ruler of the place that took his name. As he struck the terrible, fratricidal blow, he shouted (in Livy’s words): ‘So perish anyone else who shall leap over my walls.’-SPQR by Beard.

Before the twin babies, Romulus and Remus, were washed away to their death, the famous nurturing wolf came to their rescue.-SPQR by Beard.

We can be fairly confident that larger villages grew up, probably (to judge from what ends up in the graves) with an increasingly wealthy group of elite families; and that at some point these coalesced into the single community of ‘Rome’ whose urban character was clear by the sixth century BCE.-SPQR by Beard.

Another founding version of Rome: Throughout most of Roman history, the figure of the Trojan hero Aeneas, who fled to Italy to establish Rome as the new Troy. By the first century BCE some sort of coherence was reached by constructing a complicated family tree, which linked Aeneas and Romulus, and at the ‘right’ dates: Aeneas became seen as the founder not of Rome but of Lavinium; his son Ascanius was said to have founded Alba Longa – the city from which Romulus and Remus were later cast out before they founded Rome.-SPQR by Beard.

1600 BCE: Hammurabi’s Code in Babylon is enacted.-SPQR by Beard.

1700-1300 BCE: The Middle Bronze Age.-SPQR by Beard.

_______________________________________________________________