National Portrait Gallery

Washington DC, USA

___________________________________________________________________________

People

General William T. Sherman (1820-1891)

"War is war and not popularity-seeking." With these words to his Confederate opponent at Atlanta, General William T. Sherman displayed the attitude that made him both a successful commander and a bitterly hated figure in the South. Sherman first distinguished himself at the Battle of Shiloh, Tennessee, in April 1862, before promotion to command the Army of the Tennessee, and then the entire western theater.

In 1864, Sherman set out to demolish the Confederates' will and capacity to fight. In Atlanta, he destroyed everything of potential military value: railroads, factories, and supply depots. His army then cut a 285-mile path of destruction to the coastal town of Savannah. Thousands of formerly enslaved African Americans followed Sherman's army through Georgia. Hoping to provide for some of these people, on January 16, 1865, Sherman issued Special Field Order No. 15, which re-allocated 400K acres of land in 40-acre segments to Black families.

General Ulysses S. Grant (1822-1885)

At the beginning of the Civil War, Ulysses S. Grant served as a brigadier general until his victory at Fort Donelson, Tennessee, in 1862, when his terms were "unconditional surrender." President Abraham Lincoln promoted him to lieutenant general in 1864, granting him command of all the Union armies.

Grant created the Army of the Shenandoah, which protected the capital and routed the Confederates out of the Virginia valley. He also supported the service of ~200K Black men-close to 10% of the Union army. Black soldiers were, he declared, "the heaviest blow yet given the Confederacy."

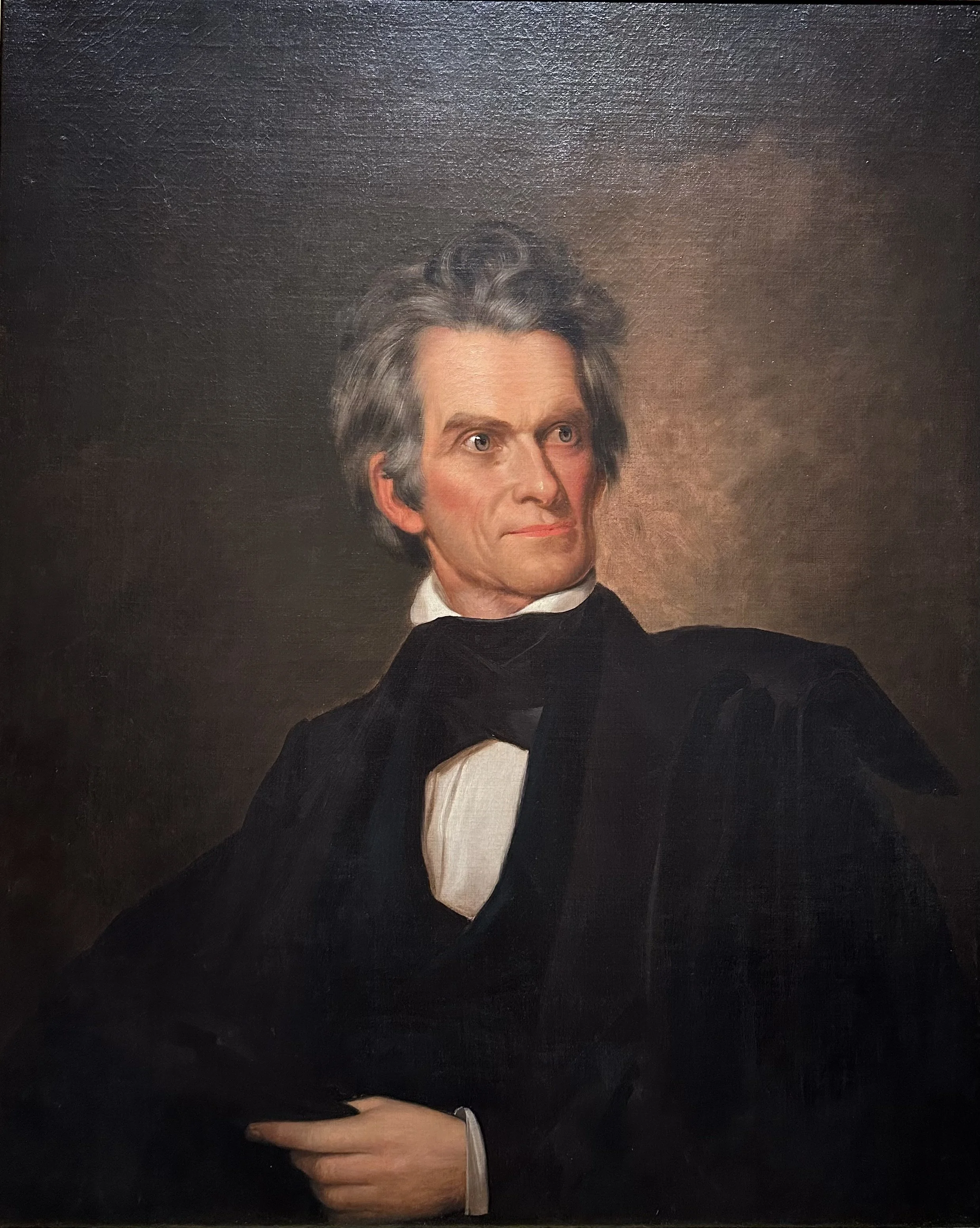

John C. Calhoun (1782-1850)

John C. Calhoun traversed the spectrum of antebellum American politics during his influential career. From 1825 to 1829, he served as John Quincy Adams's vice president but helped defeat him in the next presidential election as Andrew Jackson's running mate. A fervent nationalist during the War of 1812 (1812-15), Calhoun was championing states' rights by the 1830s.

Calhoun's white supremacist ideology justified slavery as essential to the Southern economy. While representing South Carolina in the U.S. Senate (1833-43; 1845-50), he advanced the doctrine of nullification as a bulwark against future antislavery legislation, asserting that states had the right to nullify any federal acts they considered unconstitutional. During negotiations over the Compromise of 1850, Calhoun warned that admitting Oregon and California as free states would upset the balance of power in Congress, prompting slave-holding states to secede. Although he dreaded that prospect, his ideas helped bring it about.

Senator Stephen A. Douglas (1813-1861)

One of the most powerful and controversial political figures in the nineteenth century, Illinois senator Stephen A. Douglas strongly advocated for western expansion. His goal of unimpeded settler colonialism westward was hampered by debates over slavery. Introducing the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854, he cried from the Senate floor, "You cannot fix bounds to the onward march of this great and growing country. You cannot fetter the limbs of the young giant." Hoping to quell controversy, Douglas developed the theory of "popular sovereignty," which permitted settlers to decide for themselves, by vote, the status of slavery in new western territories.

Under pressure from Southern democrats, Douglas included a provision to repeal the 1820 Missouri Compromise, which outlawed slavery from the region. Kansas exploded into proslavery and anti-slavery factional fighting and violence, precipitating the Civil War. Douglas lost the 1860 presidential election to Abraham Lincoln.

US President John Quincy Adams (1767-1848)

Following his distinguished political career as an ambassador, senator, secretary of state, and U.S. president, John Quincy Adams represented the state of Massachusetts in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1831 until his death in 1848. As a congressman, Adams became a forceful voice against slavery and a powerful opponent of politicians angling to create new slave states in the West. He opposed the Mexican-American War (1846-48), correctly predicting it would become "a war for slavery," and repeatedly defied a gag rule against presenting antislavery petitions to the House.

In 1841, Adams successfully argued before the Supreme Court that African prisoners who had rebelled against their captors on the slave ship Amistad were deserving of freedom. During his two-day argument, Adams repeatedly directed the justices' attention to copies of the Declaration of Independence displayed in the courtroom, asserting "I ask nothing more in [sic] behalf of these unfortunate men, than this Declaration."

John Brown (1800-1859)

Amid the festering hostilities between North and South in the 1850’s, John Brown's zealous opposition to slavery grew. After leading retaliatory strikes against proslavery mobs in Kansas in 1856, he began making plans for the 1859 raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. Brown intended to commandeer firearms and initiate a slave rebellion. The plan failed, and Brown was captured, tried, and hanged. His insurrection found favor among many Northerners sympathetic to his cause. In the South, however, Brown's actions signaled that slaveholding states must either face diminished power against an increasingly abolitionist North or sever ties with the United States.

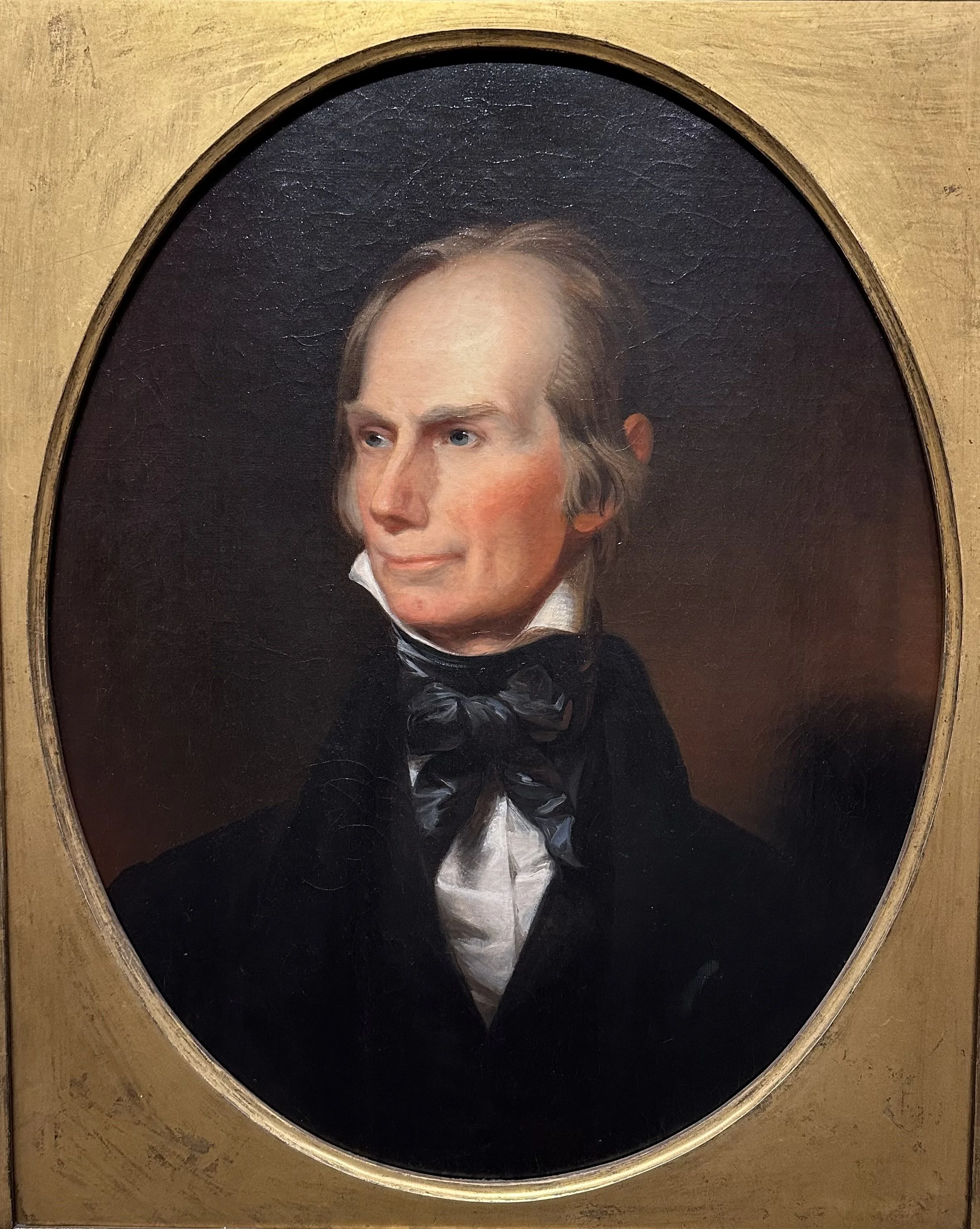

Henry Clay (1777-1852)

Henry Clay devoted his political career to unifying an increasingly divided nation. While representing Kentucky in the House of Representatives and the Senate, Clay invariably sought a middle course between polarized positions. He became known as the "Great Compromiser" after orchestrating the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which preserved the balance of power in Congress by simultaneously admitting into the Union the slave state of Missouri and the free state of Maine. Toward the end of his life, with the North and South on the verge of armed conflict over the extension of slavery into the new western territories, Clay attempted to resolve the conflict through an ambitious "omnibus bill" that became the Compromise of 1850.

Clay's personal engagement with slavery presents his penchant for compromise in a less than flattering light. Although he condemned slavery as a "universally acknowledged curse," he accepted the moral contradiction of being an enslaver himself.

Henry Beecher Stowe (1813-1887)

In response to the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, Harriet Beecher Stowe began writing a novel intended to reveal slavery as "the essence of all abuse." The result was Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly. The groundbreaking bestseller so altered attitudes toward slavery that it has been described as "one of the most successful feats of persuasion in American history." First serialized in the National Era newspaper, Uncle Tom's Cabin appeared in book form in 1852 and sold more than three hundred thousand copies during its first year in print. An international success, it contributed to the abolition of serfdom in Russia following publication there in 1857 and fueled Britain's refusal to recognize the Confederacy during the Civil War.

___________________________________________________________________________