Museum of Indigenous Amazonian Cultures

Ref: Museum of Indigenous Amazonian Cultures (2025). Iquitos, Peru.

___________________________________________________________________________

Amazonian Cultures

Tapirapé: An ethnic group of the Mato Grosso that inhabit the area of the Urubu Mountain range. The Tapirapé people rely heavily on their shamans for both emotional and physical security. They believe that to successfully conceive a child the shamans must deliver a 'child spirit' to their mother. The children's spirits are believed to reside within the Urubu mountains; specifically in an area they call Yrywo'ywawa (the place where the white vulture drinks water). The shamans must travel in their dreams to this mythological place and secure the spirits of children to deposit in the wombs of women. In their dreams, shamans also travel to the 'house of the peccaries' where they hold sexual relations with the female white-lipped peccaries to increase the size of the herds and ensure ample hunting for ceremonies. Shamans are also responsible for events such as deaths and if a shaman is suspected, the deceased's family will not hesitate to revenge him.

Xavante: Live in the east of Mato Grosso and call themselves A'uwe ('people'). Central to the Xavante culture is the masculine Wai'á ceremony, where men learn to communicate with spirits. Essential details of the meeting with the spirits takes place in a secret location away from the village. There is thought to be a transfer of power that forms the essence of masculinity for the Xavante. After the ceremony, the men emerge with their spiritual vocation and may become healers, interpreters of dreams or ceremonial singers.

Araweté: Occupy an area on the banks of the Igrarapé Ipixuna River, a tributary of the Xingu River in the south of the state of Pará. They exist through hunting and gathering and lead a very simple life possessing few material goods. The commodities they do maintain however are quite unique to them; the bow, made from Ipé wood and generally shorter, broader and more curved than most indigenous bows.

Ribaktsa: An ethnic group inhabiting the Juruena River basin in NW Mato Grosso state in Brazil. The group's name means 'the human beings'. Also known by outsiders as "Canoeirios" (Canoe people) in reference to their talent in canoe use, or "orelhas de Pau" (wooden ears) due to the men's habit of enlarging their earlobes and wearing wooden earplugs to symbolize their status as hunters. Ribaktsa were only contacted by westerners at the end of the 1940's, though they were well known by their neighboring societies for being ferocious and having hostile relationships.

The Ribaktsa believe in reincarnation, and that the future of a person's soul depends on how they have led their life. The honourable may be re-embodied as a night monkey, one of the very few animals the Ribaktsa will never kill. Conversely, those who have committed many wrongs will return as dangerous animals such as poisonous snakes or jaguars.

The Ribaktsa are known to be exceptional flute players and their feather adornments including headdresses, armbands and nose pins are considered to be some of the most striking amongst the Brazilian Amazon. Many ceremonies are held throughout the year ritualizing activities such as hunting, fishing, gathering and agriculture. The two principal ceremonies are the green maize ceremony held in January, and the clearing of the forest ceremony in May during which events, boys and girls often go through rites of passage. For males, their earlobes are perforated and they are given a new name, and for girls, along with their new name they are given facial tattoos and their nose is perforated. Unlike most tribes, Ribaktsa do not practice isolation of young girls after their first menstruation. Ritual music and feather adornments are fundamental during these events in conveying and enhancing mythical stories and recent episodes of combat by men of the community.

Karajá: A river dwelling society who has resided on the inland Island of Bananal next to the Araguaya River in Mato Grosso since pre-Columbian times. The Karajá call themselves by the name Iny which means 'us'.

In Karajá mythology the ancestors once lived in a village at the bottom of the river as underwater people. One day, curious of the surface world, a young Karajá man found a passage and surfaced, where he discovered fascinating beaches and vast spaces to live in, so he called upon his people to join him. However, many of them became ill and so attempted to return, but were stopped by a giant snake that guarded the passage under the commands of Konoi, the underwater chief. The people resolved to spread up and down the Araguaia River with the help of their culture hero Kynyxiwe and learned how to fish and live off the land. Kynyxiwe married a young Karajá woman and they went to live in the sky village. Today the Karajá live along the Araguaia River and each village has houses set in two parallel lines partitioned into three segments.

The Hetohoky is one of most important rituals held throughout the year. Boys usually go through this rite between the ages of 10-12. In preparation the initiates are painted with bluish-black genipap. The host village receives visitors dressed in their most vibrant ornaments including the lori-lori and laheto headdresses worn by men. A huge party transpires involving ritual dances, singing and fighting that can last all through the night. The next day the boys are taken to the Hetohoky or Big House where they remain for seven days, during which time they receive advice and guidance from their family members about their culture, conduct and how to be a good hunter and fisher. When the initiate finally leaves the Big House, he is a man bearing full adult responsibilities.

Yaguas: A wide-spread group originating from Pevas in the region of Loreto in Peru. They do not call themselves Yaguas, but go by the name Nihamwo which means 'the people'. They rely on the forest for their native dress typically called a 'grass skirt', which is actually made from fibres of the aguaje palm (Mauritia flexuosa). They are also known to colour fibres and paint their skin with the red dye named achiote which comes from the fruit of the Bixa Orellana tree. This dye is widely used across many indigenous Amazonian societies, for ceremonial use or everyday attire; however, to each it has a different local name. The Yaguas are also famous for their blowguns, although much shorter than those of the Matís, they are extremely effective. Their close relationship and reliance on the surrounding forest is also revealed through their traditional dances (atunas) and festivals (masatiadas) where music is performed using their native instruments, the flute (sutendiu) and drum (chinu).

Matsés: Also known as the Mayoruna, they live along the Yavari River, within the Vale do Javari Indigenous Territory and in Peru. While many other ethnic groups of the Amazon hunt with blow-guns, the Matsés are excellent makers and manipulators of spears and bows and arrows. The Matsés maintain a rich variety of myths and ceremonies, typically with the aim to help sharpen hunting skills. The poison frog ceremony is just one of those, involving the application of a toxin from a poisonous frog (Phyllomedusa bicolor) to several open flesh wounds made by burning on the arms of men and abdomens of women. The body's response is very intense causing raised heartbeat, vomiting and extreme lethargy, but ultimately resulting in an intense feeling of euphoria and heightened senses of sight, hearing and smell which enables them to hunt better and for long periods with greater precision. There are also rituals that are intended to protect children from the spirits of the animals that their parents may have killed or eaten. These are comprised of medicinal baths given to the infants using specific leaves called neste, recognized and collected only by the elders. For example, only after their child has been bathed with the appropriate plant infusion, may the parents kill or eat strong meats such as the spider monkey or tapir, or notoriously dangerous animals like large snake or jaguars.

Marubo: Live in the Vavart basin on the upper parts of the Curuçá and tul rivers at the frontier between Brazil and Peru. They are one of a number of ethnic groups that reside within the Vale do lavari Indigenous Territory. In Marubo mythology, the universe was created by beings created from the transformation or accumulation of other dead or destroyed beings. The Marubo believe this happened recently when their society had to be rebuilt after being destroyed, fragmented and practically extinct as a result of the rubber boom.

Unlike many Amazonian societies, the Marubo do not practice any specific rites of passage when teenagers go through puberty. However, there is some distinction among men regarding tobacco, snuff and ayahuasca as they do not use these substances until they reach the age of around 30. Prior to this age, a young man's role in society is to assist the older men in their task.

The Marubo are recognized for their shamans and curing chants which all elder men are obliged to participate in, presenting a complex medicinal wisdom involving the use of a wide diversity of native plants, herbs, barks, resins and roots.

Common to most Amazonian ethnic groups, there is a distinct difference in the daily tasks of Marubo men and women. Men clear land for agriculture, hunt and construct canoes, log drums, wooden mortars and benches. Women manage the gardens including harvesting, the manufacture of ceramics and palm fiber hammocks as well as their characteristic variety of shell jewelry.

Shipibo: Live in scattered communities along the banks of the Ucayali River in eastern Peru. The Shipibo are predominantly famous as skilled artisans and for their intricate geometric patterns which they portray on their crafts. The Shipibo believe the visible world was once embellished in these lavish designs and now the invisible spiritual world of their religion is reflected by the beautiful patterns that are placed on their crafts, the sky, forests, huts, people and animals were all covered in a continuous network of design. Due to the misdemeanors of unsuccessful humans, this sublime union of the geometric lineaments ruptured and split into three overlaid planes suspended one over another; the sky world (Nëte Shama), the earth world (Mai) and the underwater world (Jene Shama). At the same time night and day cycles occurred. Today Shipibo continue their design through their textiles, fine-ware ceramics, and many other objects, are also reminisced and praised in song.

Despite their deep-routed traditions little is actually known about the precise messages portrayed in the complex geometric designs, though the elders still retain some knowledge of spiritual origin and therapeutic applicability of certain motifs.

According to myth, the wisdom of designs belongs to Ronin, the Great World Boa, on whose tari (skin), all patterns are united.

Another explanation of derivation is the hallucinogenic visions of male shamans and post-menopausal female shamans (Muraya) during ayahuasca sessions, said to illuminate brilliant geometric patterns against the night sky. These patterns are deemed 'medicines' bestowed to the shamans by the spirits. It is their responsibility to deliver these designs onto the women entrusted with their artistic materialization, as well as using invisible designs to heal spirits.

The Shipibo maintain a matrilocal culture where men live with their wife’s family and women assert a strong position in society. Women are the primary artists among the Shipibo and this is reflected in many of their myths. Their most important public event, the ani shreati (great drinking feast) is celebrated as the puberty ceremony for females and not males. Within this ceremony Shipibo in the past traditionally held the custom of clitoridectomy (removal of the clitoris) of the young girl in order for her to marry. Although this operation is prohibited today, the feasting and drinking that accompanied the ritual still continue.

Unlike many Amazonian groups, the Shipibo do not use hammocks or raised platform beds to sleep in but instead sleep under their mosquito nets on a simple mat on the floor.

Ashaninka: Belong to the Campa ethnic group, originating in Peru in the eastern foothills of the Andes. They are fragmented into several sub-groups with varying dialects and differing names. Some have spread further however, as far as the Amazon River in Brazil. The social structure of Ashaninka is simple, designed around single-family units living in isolation or close to a few related families. The Campa do have chiefs known as curacas, a responsibility that is inherited patrilineally, although their authority is generally limited to agriculture, hunting, fishing and fighting.

The Campa are not renowned for their lavish festivals or masked dances of which there are almost none, but more for their intimate relationship with nature and their belief in the divinity and sacredness of the forest that is there to nurture them. Mary natural ailments are treated using medicinal properties of local herbs, plants and minerals. Magical substances are employed as remedies, such as the toad gall bladder which is taken for eye trouble, and monkey gall prescribed for tooth-ache. These therapies are extended to command good omens such as courage from a wildcat's heart, or divinity from their gallbladders. Supernatural diseases also exist, which can only be cured by a shaman. These afflictions are believed to be caused by a "bone that is thrown into the victim's body by a sorcerer disguised as a jaguar, or by a snake that bites the victim under the orders of an enemy shaman.

Kukama Kukamilla (previously ‘Cocama Cocamilla’): A widespread group inhabiting long stretches of floodplain ecosystems of the lower Cayali, Maranon and upper Amazon Rivers in Peru. There are written documents about the Cocama dating from the 1600's by Jesuit missionaries, and the mission seat in Maynas was Lagunas, situated alongside the 'Lake of the Great Cocama'.

The Cocama are renowned for their excellent adaptation to living in floodplain ecosystems and their communities are always found inhabiting long stretches of riverbanks. Traditionally the Cocama dedicate themselves to fishing and agriculture, with hunting and gathering being supplementary activities. The value of fishing to the Cocama is evident in their myths of origin, in which their culture hero Ini Yara, is represented as a great fisher who goes, roaming the lakes and rivers in a canoe or floating raft. The importance of becoming a good fisherman is also reflected in traditional maturity rituals. In one such ritual, the vein of an electric eel is tied tightly around a boy’s arm. Over time the vein leaves a scar in the form of a ring around the arm, a sure sign that the animal's impressive energy has been transferred. It is believed that as the boy grows into an adult, with this acquired strength he would be able to launch his fishing instruments with extraordinary force to kill even the largest aquatic animals. Over centuries, the Cocama have developed an array of different instruments and techniques for fishing, which today are a legacy inherited from their ancestors. As such they also have a reputation amongst similar riverine groups as the great fishermen' of Loreto, the area where they were first documented.

The Cocama possess a remarkable community spirit and internal organization that is mostly centered around strong kinship relations. This ideal is highlighted through the practice of the ajuri, which involves collective work undertaken by various groups of families to build something for the community or help out one family. The most common example of the ajuri happens every year when families group together to clear land, preparing the soil for their gardens. This collective activity is then religiously followed by a communal meal and copious amounts of their traditional drink masato.

___________________________________________________________________________

Voluntarily Isolated Indigenous Communities

Voluntarily Isolated (‘Un-contacted’) Indigenous Communities: Communities who live by choice or circumstance, without contact with civilization. Throughout S. America there are ~100 or more voluntarily isolated indigenous groups, with the majority occupying areas of the Amazonian Forest in W. Brazil and E. Peru. Most of these communities have had a history of contact at varying levels, whether it was through past exploitation or simply overflying planes. In fact, it is most frequently past experiences of contact and fear that motivate groups to remain isolated, and commonly results in hostilities when contact is attempted.

Ever since the Spanish conquistadores arrived in South America in the 16c, indigenous peoples were exploited and often murdered or enslaved by outsiders. Even people with peaceful intentions, such as the missionaries, brought disease to the communities that had no immunity and thus were often wiped out in great numbers.

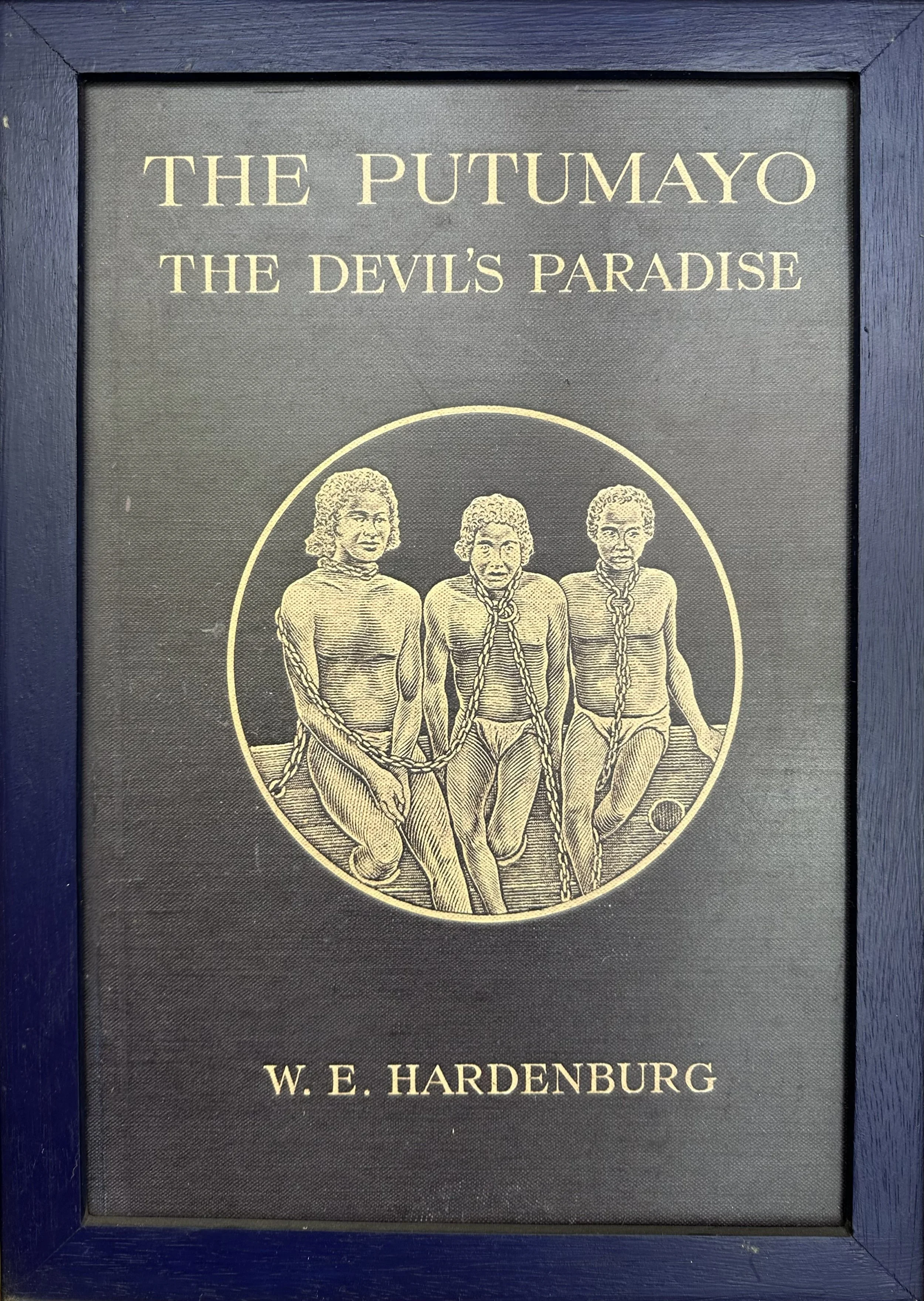

Many indigenous groups were treated horrifically during the rubber boom period between the years 1880-1912. Atrocities, including floggings, beatings, rape and murder were inflicted upon some indigenous peoples by ruthless rubber tappers. Many who suffered from the dreadful experiences fled into the forest vowing to themselves never to have contact with the horrors of the outside world. Through generations, these "voluntarily isolated" groups have passed down through their oral history the need to remain hidden in the forest in order to avoid the atrocities that they so greatly fear.

The overwhelming trend of negative experiences with outsiders meant that indigenous groups quickly learned to fear the white Europeans and have passed the message on to neighbors and down generations through vocal histories.

"Voluntarily isolated" indigenous communities are often in conflict with economic expansion and isolated groups now face threats from mining, oil and gas operations, illegal loggers, agricultural expansion and drug traffickers. Deaths occur from direct hostile encounters and from diseases that outsiders carry, unknowingly infecting these indigenous people who have no immunity to western ailments. The Peruvian and Brazilian governments are working to help the "voluntarily isolated" communities and have marked out restricted areas as indigenous reserves in attempts to reduce conflict and avoid disease.

___________________________________________________________________________

Chronology

1880-1912: The Western Amazon’s Rubber Boom Period (Museum of Indigenous Amazonian Cultures).

___________________________________________________________________________